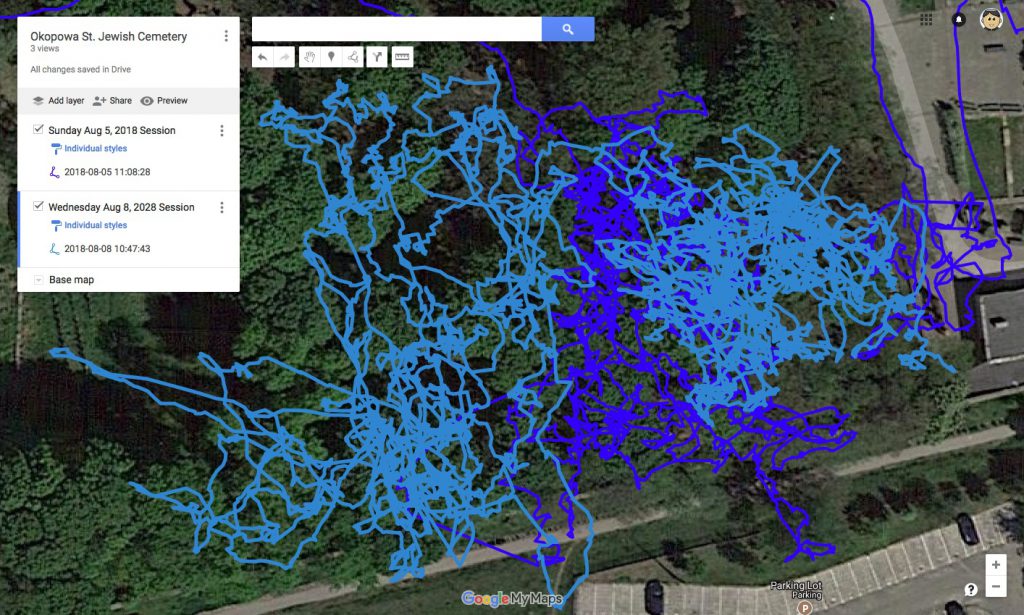

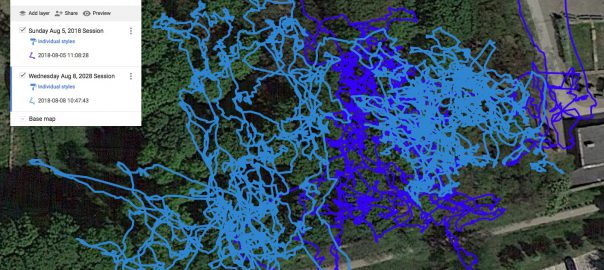

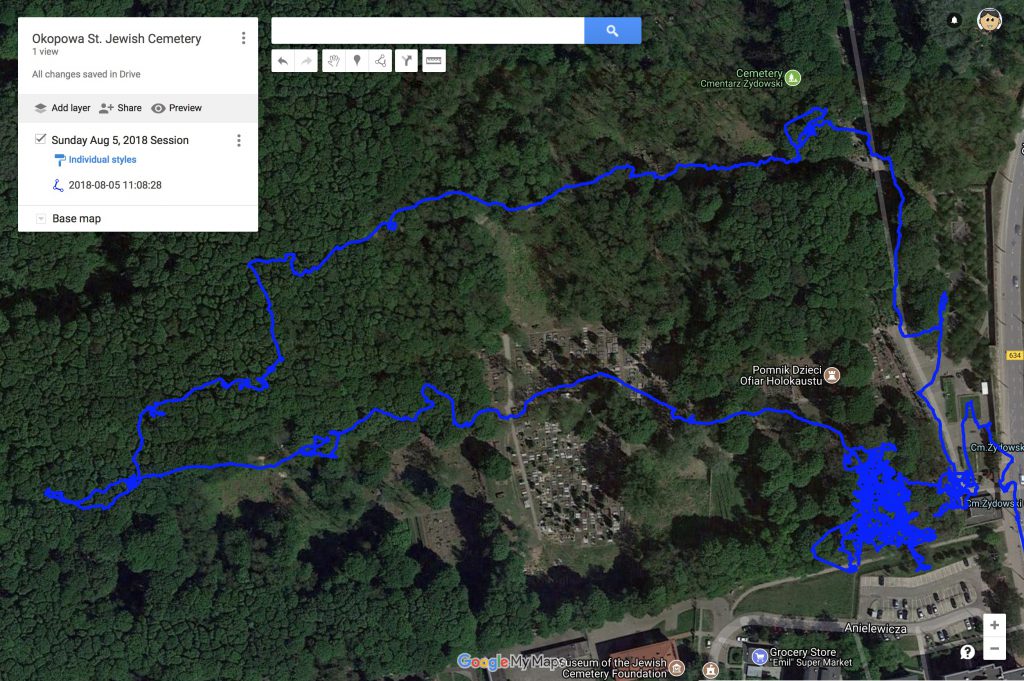

I’ve fielded many questions about the Okopowa St. Project I announced yesterday. Many of the questions have centered on the need for doing this, considering there is an existing database of photos from this cemetery, with tens of thousands of photos. While the goal of this project is not primarily to document the Okopowa St. Cemetery, but to experiment and learn from the process, I do think addressing the broader issue of doing cemetery research online is worth tackling.

Cemetery research is an important part of any genealogy search, even more so for Jewish genealogy, where Jewish gravestones usually provide the first name of the father of the person buried. That ability to jump a generation back can be very important when researching Jewish families.

There are many resources for doing cemetery research, but on a global scale for Jewish genealogists, there are only a few.

In the case of the Okopowa St. Cemetery, the primary resource is the aforementioned database, which is published by the Foundation for Documentation of Jewish Cemeteries in Poland (FDJCP). This database has 82,325 entries. I’ll get to the photos in this database in a moment, but one downside to this database is a lack of phonetic searching. If you search for ‘Cohen’ you will get no results. Search for Kohen and get results. That’s an obvious one, but considering many of the graves were in Hebrew and transcribed to English, there is no way to know if the spelling guessed by a transcriber was the same one known by a relative.

In the case of the Okopowa St. Cemetery, the primary resource is the aforementioned database, which is published by the Foundation for Documentation of Jewish Cemeteries in Poland (FDJCP). This database has 82,325 entries. I’ll get to the photos in this database in a moment, but one downside to this database is a lack of phonetic searching. If you search for ‘Cohen’ you will get no results. Search for Kohen and get results. That’s an obvious one, but considering many of the graves were in Hebrew and transcribed to English, there is no way to know if the spelling guessed by a transcriber was the same one known by a relative.

The largest database of Jewish burials is the JewishGen Online Worldwide Burial Registry (JOWBR) which has information on over 3 million burials worldwide. JOWBR is an amazing project, but like any volunteer effort is dependent on what its volunteers can produce. In the case of the Okopowa St. Cememtery, it has information on less than 200 burials, and no photographs.

There are two large burial databases that are not specific to Jewish burials. The first one is FindAGrave.com, which was originally an independent project, but is now owned by Ancestry. FindAGrave originally had a focus of documenting celebrity graves, and built a community of people to photograph and manage profiles of buried people. FindAGrave says they have information on 480,840 cemeteries in 240 countries. In the case of the Okopowa St. Cemetery, however, they only have profiles of 121 burials, of which only 47 have associated photos. Of those 47 burials, many of the photographs are not actually of the gravestones, but photos of the people themselves that have been submitted by people online.

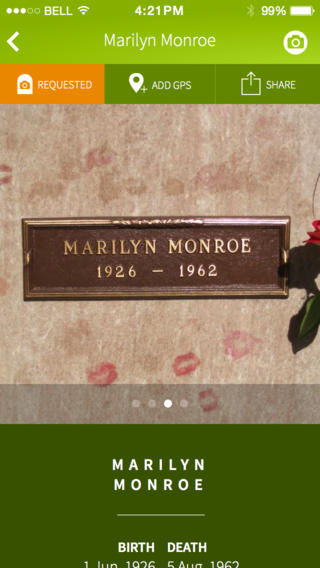

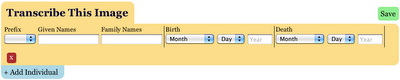

The second and more recent online database was created by the company BillionGraves. BillionGraves took advantage of the fact that the new smartphones coming into the market had cameras, built-in GPS, and Internet access. That allowed them to write an app that could capture photos of gravestones with their exact location, and upload them straight to their web site without needing to document anything about the graves. The information could be transcribed later on the web site. This allowed volunteers to rapidly build databases of entire cemeteries. Not long ago MyHeritage, the commercial genealogy company, partnered with BillionGraves to use their technology to collect photographs of all the gravestones in Israel (something IGRA also participated in by proving volunteers to take the photographs). BillionGraves flipped FindAGraves’ model on its head, as instead of creating a profile of a person and then adding photographs of their grave (which needed to be located), BillionGraves starts with the photographs and adds the information later. Concerning the Okopowa St. Cemetery, BillionGraves only has 216 burials documented.

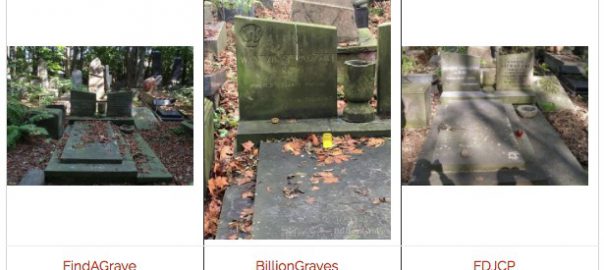

I think it’s useful to take a look at the varying quality of photos across these sites, but as you may have figured out by now, that’s almost impossible. JOWBR has no photographs of this cemetery, and FindAGrave has only about 20-30 gravestone photos. What are the chances that among those 20-30 photos, the same graves were documented on BillionGraves? It turns out there is at least one.

Wanda Sieradzka de Ruig died about ten years ago. Here are three photos of the her grave site from the three databases that have photos:

Now, this gravestone is not the best example, because unlike many graves in the cemetery, it is not densely covered in text. It’s also relatively recent, so the text is not worn down. What we can see, is that even with that being true, the FindAGrave photo of the gravestone is hard to read, as it’s perhaps taken too far away. I always like a wide shot of a gravestone to give some context, but that shouldn’t be the only photo. There should always be a close-up photo of the text of the stone.

BillionGrave’s photo is actually closer up, and easy to read. Unfortunately, you can’t see the spouse’s information, and you can see there is some text on the surface closer to the photographer, but it’s cut off. It’s worth noting that in the FindAGrave photo this text was covered in fallen leaves, so it can’t be seen at all.

The FDJCP photo is wide like the first one, but still closer and of better quality. It’s still difficult to read the text facing up on the stone, but overall this is probably the best image.

Let’s take another example. In this example, the grave is only on two sites, BillionGraves and the FDJCP site:

At first glance, the BillionGraves photo is superb. It’s well framed, the text is clear, and the lighting is even. Of course, looking at the second image, one realizes that the Polish text in the BillionGraves photo is only one side of the gravestone with text, and there’s a whole different side with text in Hebrew. However, looking at the FDJCP image, the angle for both sides makes it much harder to read. The Polish is readable, but the angle, the uneven lighting on the Hebrew side, and the small size of the Hebrew text relative to the whole image, makes it very difficult to read. Better than not including it at all, but difficult to be sure what you’re reading. The photographers working for the FDJCP may have photographed the text closer up for indexing purposes, but FDJCP only includes one photo, and in this case that makes it hard to read. I wonder what they do in the case where text is on opposite sides of the stone?

When I photograph gravestones, I like to take at least three photographs, and in some case more, per gravestone. These photos include a wide photo showing it in the context of its location, a photo of the entire gravestone without the wider area, and a close-up of the text on the stone. If I need more than one photo to capture all of the text, such as when it is on different sides, I always take extra photos getting all the text. For those who have read my article on Jewish Gravestone Symbols, you also know I like to take photographs of the symbols on gravestones. The Okopowa St. Cemetery is particularly rich in these symbols.

For the above gravestone of Izrael Frenkel, for example, I would have taken one wide shot of the entire gravestone, probably showing both sides of text. I might take a closer image showing both sides as well, but I definitely would have taken one straight in front of each side of text, and cropped to include only the text. Probably then I would have four photos of this gravestone.

Let’s take one last example that is only on the FDJCP site:

I have no way of knowing why the above photo is angled the way it is, or why the bottom is completely cut off. Maybe there’s something out of the frame that blocked the photographer from taking a picture straight in front of the gravestone. Maybe the bottom part of the gravestone is blocked by something and photographing the bottom wasn’t possible. While these things are possible, I don’t know if any of those are true since there is no photo to provide context. Even if all of that was true, it seems from what you can see that it should have been possible to get a photo of the text closer up.

So to be clear, while the primary goal of the Okopowa St. Project is more about experimentation and learning than it is about photographing gravestones, it will still be nice to have new high-resolution photos of many of the graves.

In the case of the Okopowa St. Cemetery, the primary resource is the aforementioned

In the case of the Okopowa St. Cemetery, the primary resource is the aforementioned