This is a touchy topic I think, mainly because there are so many reasons individuals do genealogy, and moreover people have very different connections to their families, and in some related fashion connections to their genealogical work.

This article is a more general view, but if you’re interesting in finding out why I, specifically, do genealogy, my recent guest-post on The Scrappy Genealogist’s blog titled Philip Trauring – How He Does It – Secrets from a Geneadaddyblogger is probably the best exposition on that topic (as well as why I blog about genealogy).

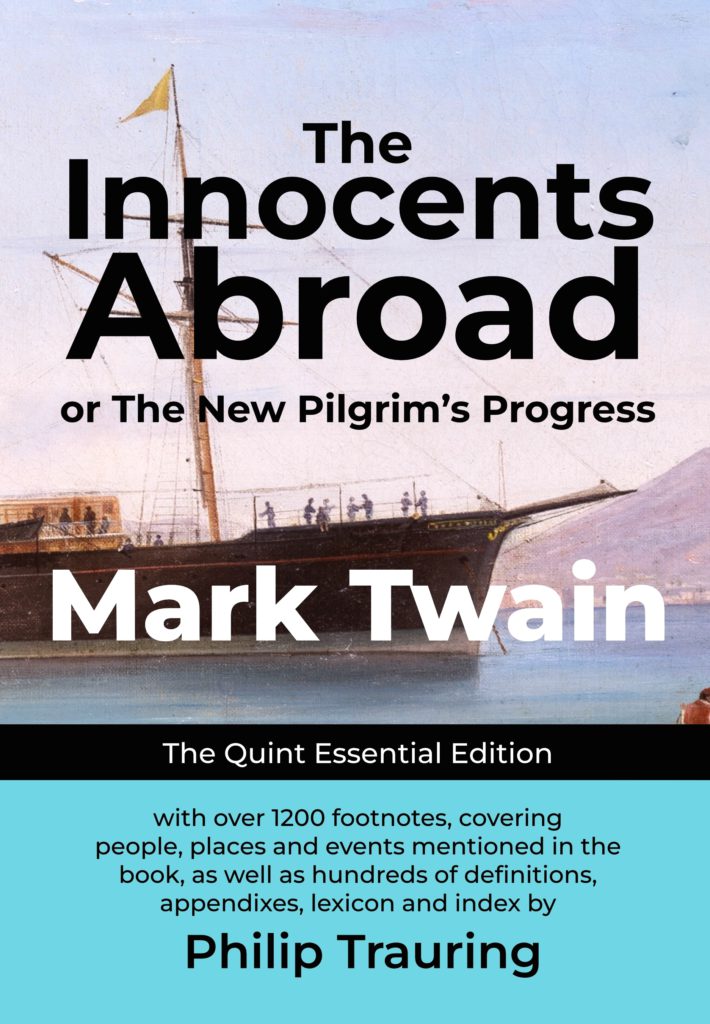

This article is partly a book review, or rather it is a book review intertwined with my view as to why people do genealogy. I’m not sent books to review by genealogy or Jewish publishers, and in any event this book was published by the University of Nebraska Press, so yes I bought this book to enjoy it. The book is What They Saved: Pieces of a Jewish Past by Nancy K. Miller. I wasn’t familiar with Ms. Miller’s work before, and perhaps if I had read some of her other books, including an earlier book on the death of her father, I might have had a different perspective, but I’ll write my impression based on the book as it stands on its own.

by Nancy K. Miller. I wasn’t familiar with Ms. Miller’s work before, and perhaps if I had read some of her other books, including an earlier book on the death of her father, I might have had a different perspective, but I’ll write my impression based on the book as it stands on its own.

Of course, nothing stands on its own. I came to be interested in the book because it related to genealogy, and specifically Jewish genealogy. That background colors my view of the book, to be certain, as does my own history.

The book’s title, What They Saved, is as good as any place to start. Maybe I’m crazy, but the title strongly reminded me of Tim O’Brien’s collection of Vietnam-based fictional stories, The Things They Carried. Miller is a professor of English and Comparative Literature, as well as a literary critic, so I would guess she has read the book or is at least aware of it. I am not a literary critic, so perhaps the convention used in naming both books is some know method (The Third-Person Perspective Descriptive Method – I’m kidding), but it still struck me for some reason as connected. As Ms. Miller is a literary critic, I hope she doesn’t take offense at me pointing this out (or anything else I’m about to write).

So why do we do genealogy? It’s a question many people reading this have probably asked themselves, but even more likely it’s a question the people reading this article have been asked by others repeatedly. Why do you do genealogy? Why do you care about people who have been dead for a hundred years? What are you going to do with all this information you’re collecting? The questions come in many forms, but most people who spend a lot of time doing genealogy get asked the same thing again and again.

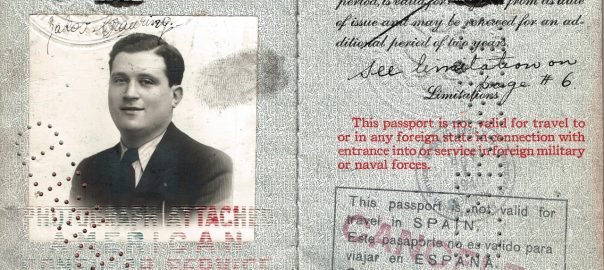

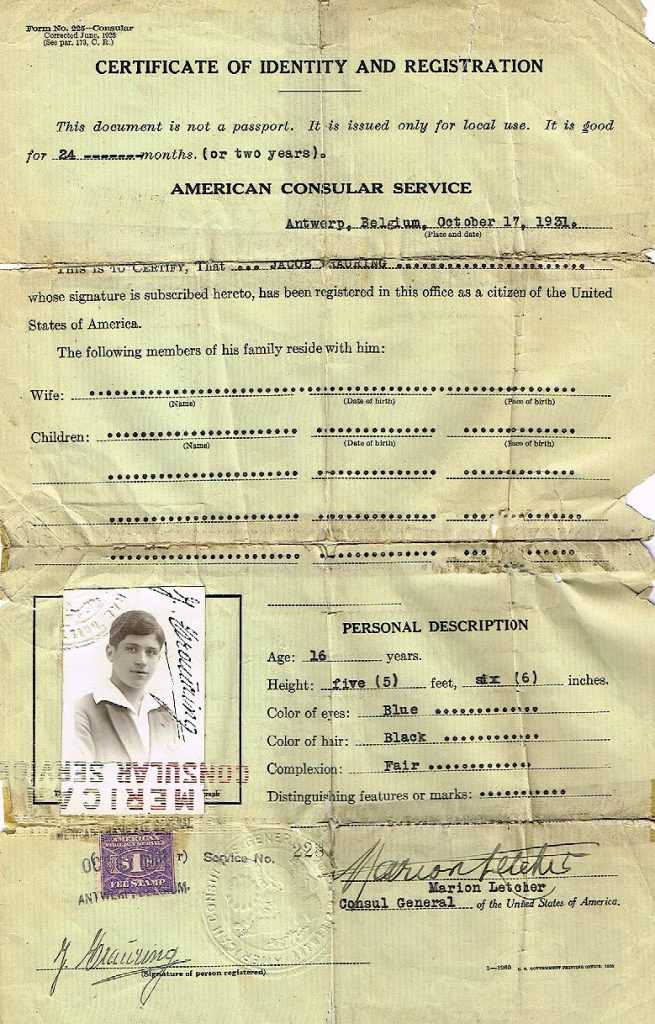

Before answering the question, I think it’s worth taking a look at why Ms. Miller decided to pursue her own family history. Her grandfather was a religious Jewish immigrant to the United States, coming with his wife and son. Her father was born in the US after her grandparents and uncle immigrated. Her father and uncle took very different paths in their lives, her father the upstanding lawyer, her uncle a gangster-hanger-on before moving out west and going through more life-role-changes than a Rockette goes through costume-changes. Ms. Miller doesn’t spend much time in the book on her relationship with her father – perhaps that was covered in her earlier book. She instead spends a lot of time trying to track down what happened to the uncle she never knew who moved out west and was everything from a bar owner, to military man, to small town mayor, to seeming vagabond.

It’s interesting to note that Ms. Miller’s original surname, that of her father and uncle, was actually Kipnis. In her evolution to feminist activist in the 1970s she took on her mother’s maiden name, Miller, and kept it after getting married. She interestingly points out a correspondence she discovers between her father and uncle on preserving the Kipnis name (her father had only daughters and her uncle’s only son also only had a daughter), while also remembering that her father, the lawyer, helped her fill out the name-change form when she made that decision.

There is almost a melancholy overtone to the whole book, as Ms. Miller doggedly pursues the clues to her family’s past, yet openly recognizes that since neither she nor her sister had any children, there will be no one to inherit the information she gathers. Perhaps, as she points out her uncle donating personal items to a museum to be stored, alongside items belongs to Wyatt Earp and others from his region in Arizona, as a way to perpetuating the Kipnis name, she too is seeking to perpetuate the name and her family through her book.

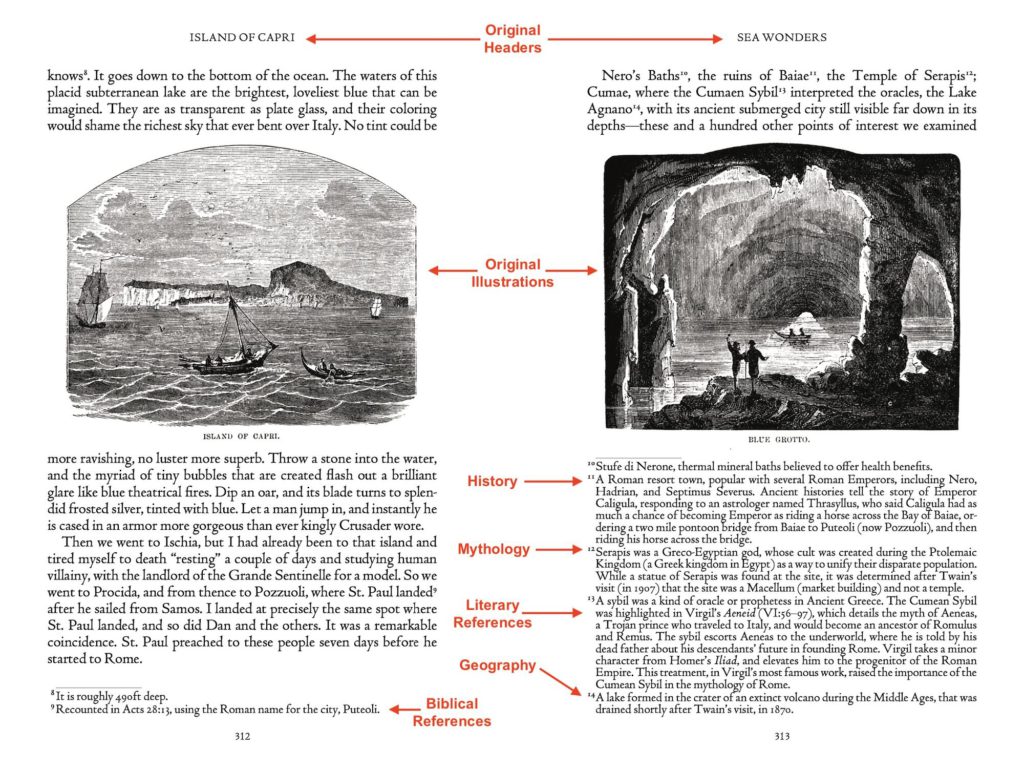

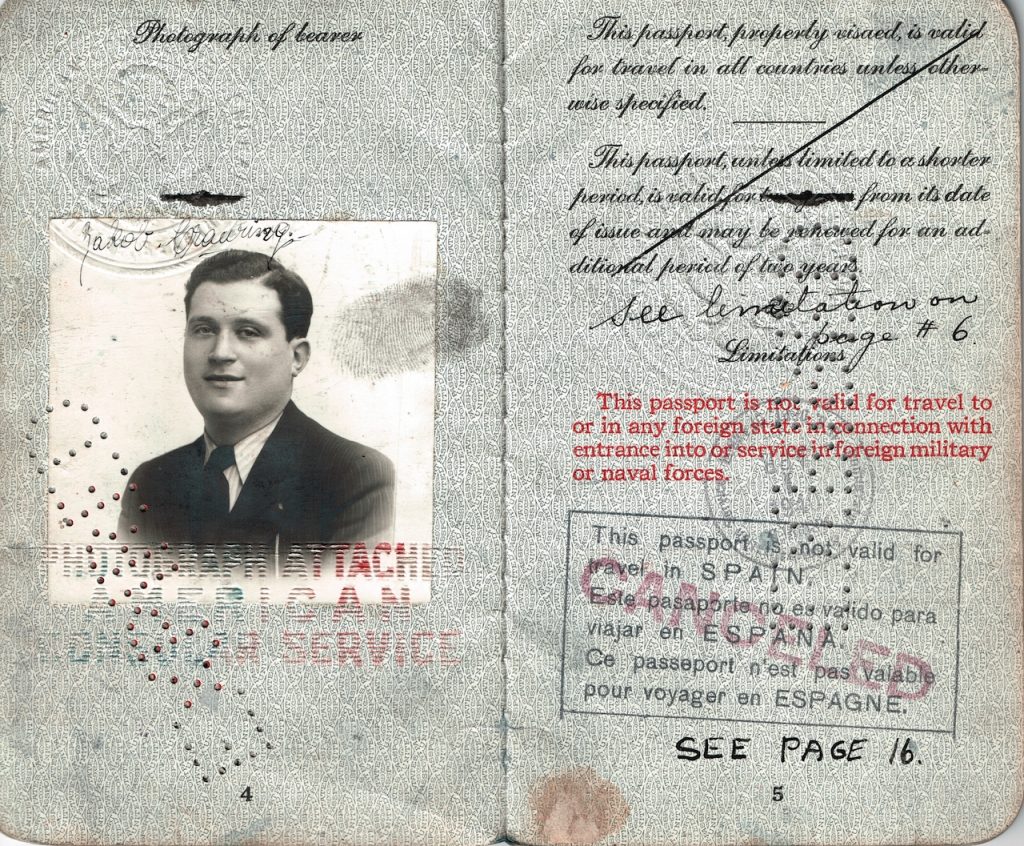

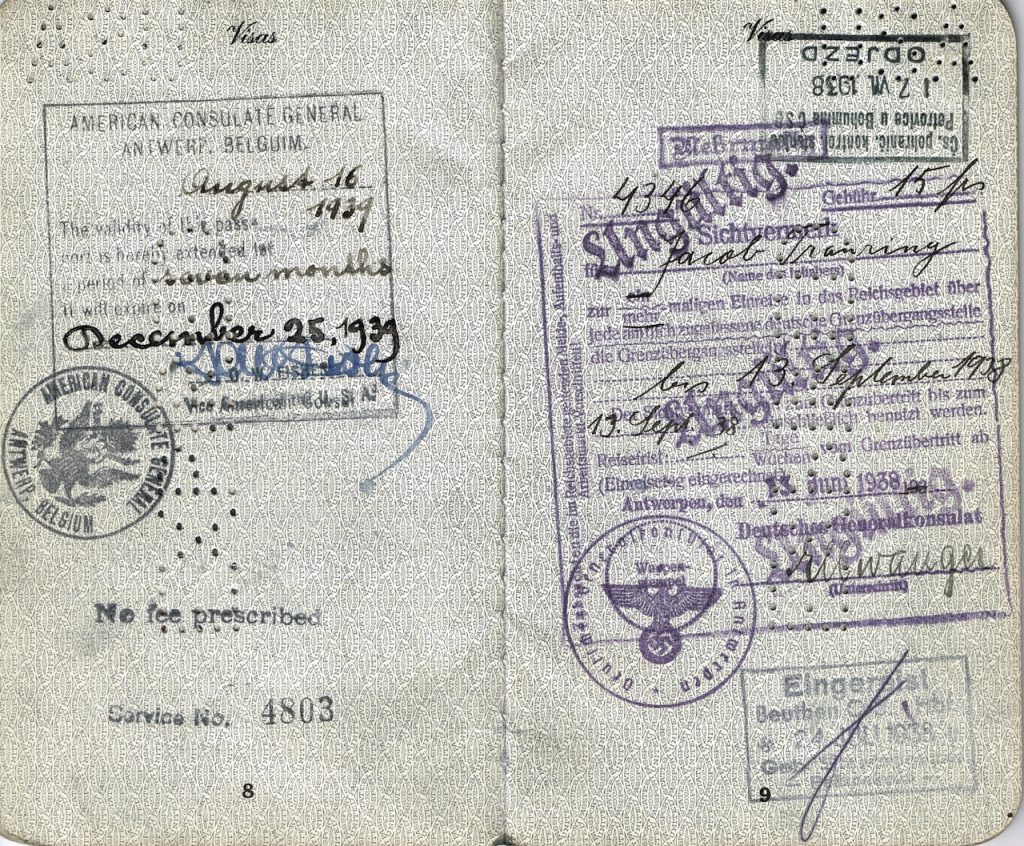

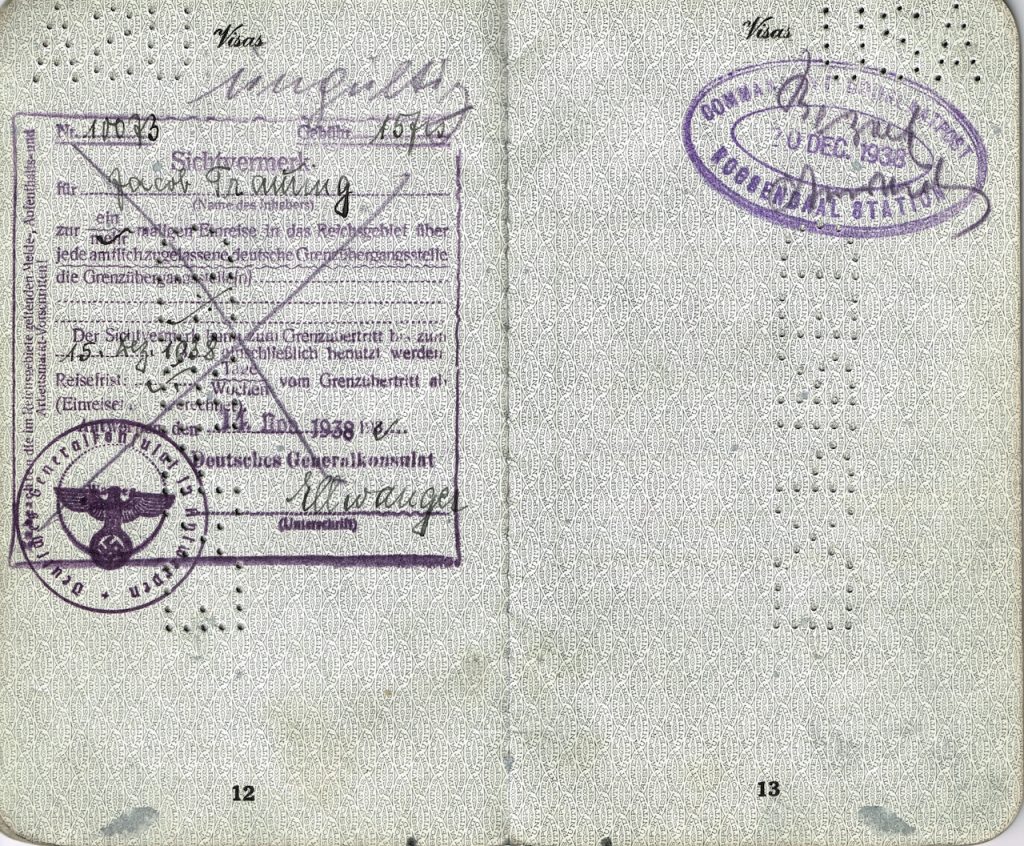

Ms. Miller’s book did not go into a lot of detail on the genealogical side, and indeed from a genealogical point-of-view it is a bit unsatisfying. The idea of taking a few found-objects left behind by your family and using those objects to reconstruct one’s family tree is a nice idea, but the amount of work needed to do that is not really described, but somewhat assumed in the book. As a family memoir it is interesting, but as a genealogy book it leaves out a few too many details. Indeed one of the simpler things I found was that whenever she would describe a truly significant item she would almost never show a photograph of that item. There are very few photographs in the book, and usually they are not particularly significant. In one instance, she shows the outside of an album which has no genealogical value (but has symbolic value) instead of showing the items she describes as being inside the album. Ms. Miller is of course a writer first, so she probably feels that it is more important to write about the objects than to show them. Perhaps that is the fault of my visual nature, a bias of mine, but it was still somewhat disappointing. Ms. Miller does add some photographs to her book’s website, although not that you would know anything about the website when reading the book – I googled the book when writing this article and only came across the site by chance.

So why do people do genealogy?

Some do it out of a strong desire to know where they originated. We are the product of our parents, grandparents and great-grandparents’ life decisions. If my gg-grandfather had moved to Israel like his in-laws (my ggg-grandparents), his world, and indeed the world of everyone that came after him would be very different. If my gg-grandfather had decided to stay in New York like his brother, rather than returning to Europe, things would also be very different. Learning about ones ancestors, and seeing how the decisions they made affected their lives can put ones’ own life choices into perspective.

Some people do genealogy as a way to connect their children or grandchildren to their past – a way of grounding them. Teenagers have a way of thinking they know better than their parents, and think everything they do is unique and their parents can’t possibly understand the decisions they have to make. While your great-grandparents didn’t have to worry about which cell phone would run the apps they need to communicate with their friends, or deal with injuries like Texting Teen Tendonitis, they made very real decisions on where to live, where to work, how they wanted to educate their children, etc. that can help your children realize that many decisions you made for them are not so different then the decisions that were made by their parents, or their grandparents, and one day the decisions that they themselves will need to make. The details may change, but the overall decisions stay the same.

Other people do genealogy as a way to connect them to people in the past, either famous people, royalty, or in the case of Jewish genealogists, frequently famous rabbis. Saying a descendant of the Vilna Gaon is kind of like the Jewish version of my ancestor was an indian princess (with apologies to those who are actually descendants of the Vilna Gaon).

For some, genealogy is about the detective story where you and your family are at the center. Some people read detective fiction for fun, others enjoy the detective work required to piece together one’s family tree. Figuring out where to find the records you need to prove (or at least mostly prove) where and when you ancestors were born is a challenge, even under the best of situations. The challenge is a major motivator for people, and successes in finding obscure records and proving theories on where different ancestors came from can be very satisfying. Breaking through a genealogical brick wall is akin to playing golf and getting a hole in one. It doesn’t happen often, and usually only happens with very experienced players (although some people get lucky), but even for the most experienced players, getting a hole in one is a reason to celebrate. So too, some genealogy is easy and some requires a lot of experience to achieve (and sometimes you get lucky), and when you find that one record that sends you back another generation, links different branches of a family that you had not previously been able to link, or directs you to an ancestral town you were not aware of, it is a time to celebrate.

I admit to not understanding every kind of genealogist. There are those who seem to have a compulsive need to add names to their family tree, but are not interested enough in the individuals they are adding to actually verify their information. If they find an online tree with some of the same people they are researching, they are likely to just download that tree and integrate it into their own, without knowing the quality of the tree they are downloading. That’s one kind of genealogist I just don’t understand. Sure, it’s easy to copy trees from the Internet, certainly easier than adding source citations to every piece of information you add to your tree. Genealogy is one of those things where I think quality definitely beats out quantity. Partly by virtue of Ms. Miller’s relatively small family, she commendably seems to have spent time trying to find as much as possible about each individual in her tree – at least on her father’s side which is the focus of the book.

Ms. Miller’s motivations seem to fall primarily in the first category described. This is brought forth by the sub-title of the book: Pieces of a Jewish Past. To whose past is she referring? Her past? The ‘They’ in ‘What They Saved’ presumably excludes it being her past. Her parents past? or that of her grandparents? maybe she is collectively referring to all her ancestors? She explains that her father had little to do with Judaism, and she herself left almost all vestiges of Judaism behind (including, as she feels the need to point out, that she and her sister married non-Jews). Yet, with all of this, she keeps the tefillin (phylactery) boxes she finds among her father’s possession as a kind of desk ornament along with photos of her family. Did her father have a stronger connection to his Jewish faith than his daughter knew, or was this pair of tefillin kept for the same reason his daughter decided to keep them, as a kind of bridge to the past. Indeed, it’s even possible the author was wrong in ascribing the pair of tefillin to her father, for he could have been keeping his own father’s tefillin in the same way his daughter kept what she thought was his.

I think this motivation, of wanting to know where one came from, is ironically prevalent among many people who start looking into their family history as they reach their retirement years. I can’t say for sure, but perhaps this genealogy is a form of introspection. You’ve lived your life and made the major decisions that put you, and possibly your children and grandchildren, in the places they are now. You start to wonder, did I make the right decisions? There’s a lot to learn by looking at how each branch your family differs. If you start out a hundred years ago and look at the different choices two brothers made, and how those simple decisions determined in large part the different lives their descendants lived, you can in some fashion extrapolate those differences to the decisions you made in your family, and how those decisions will have an effect on future generations of your family.

Why do you do genealogy?

My motivation for doing genealogy is some combination of understanding how the choices we make have a profound effect on future generations, as well as enjoying the detective work. When my children are older, I suspect I will also want to use the work I’ve done to connect my children to their past, but my children are too young right now.

So let’s continue the conversation. Why do you do genealogy? Do you fall into one or more of the categories I’ve described above, or do you have totally different motivations? Post a comment below and share your motivations for doing genealogy.