I get asked by a lot of people how to get started in researching their family. This entire site is dedicated to helping people do just that, but after eight years of writing articles and creating resources like my forms, and the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy, it’s still hard for someone completely new to genealogy to know what to do first. My goal here is to guide someone completely new on what to do first, what is useful on my site, as well as what other sites are useful. So if you’re new to genealogy, this will help you get started.

I get asked by a lot of people how to get started in researching their family. This entire site is dedicated to helping people do just that, but after eight years of writing articles and creating resources like my forms, and the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy, it’s still hard for someone completely new to genealogy to know what to do first. My goal here is to guide someone completely new on what to do first, what is useful on my site, as well as what other sites are useful. So if you’re new to genealogy, this will help you get started.

What do you already know?

It seems obvious, but the first thing you need to do is figure out what you know, which will help you figure out what you don’t know. You start this process by asking whoever in your family may know information. Depending on your age, this might be your parents, or grandparents, or whoever are the oldest relatives in the line you are researching. When reaching out to these relatives, you want to not only ask for information, but if they or another relative might have documents that show this information. Always ask if they know of a relative that has already researched the family history. Many families have a cousin that has already done research, and already collected documents and photographs. They may remember a cousin or an uncle that has collected information on the family, and even if that person is not alive now, you may still be able to find information from that relatives’ descendants.

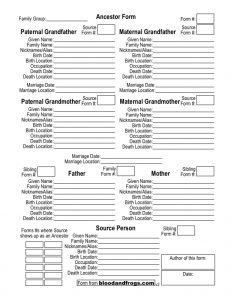

When getting started I always suggest starting with paper forms. There are many great computer programs and web sites for organizing your genealogy, and I do recommend using them but especially when meeting with older relatives, working with a piece of paper is usually easier, and it has the advantage of making it very clear which fields in the form you have not filled in yet (and thus need to ask about/research). On my site you can download several different forms, in English and in Hebrew.

I suggest starting with the Ancestor Form with yourself as the source person at the bottom, and adding in the details on your parents and grandparents. Are you able to fill in all the fields on the form? Do you know where all of your grandparents were born? What their exact birth dates were? Do you have documentation for any of the information, such as birth certificates, marriage licenses, ketubahs, passports, etc.?

I suggest starting with the Ancestor Form with yourself as the source person at the bottom, and adding in the details on your parents and grandparents. Are you able to fill in all the fields on the form? Do you know where all of your grandparents were born? What their exact birth dates were? Do you have documentation for any of the information, such as birth certificates, marriage licenses, ketubahs, passports, etc.?

Once you’ve filled out the form, add Sibling Forms for each of your parents and grandparents, or Family Forms for their parents (which will provide similar information but include the parents, and will show their siblings as children of the parents). As you work your way out further, you’ll see that you probably know less information. That’s okay – this is just the first step in building out your family tree.

When you’ve built out several of these sheets, and you see what information you’re missing, you will have a good idea at least for what information to starting looking for.

Up, Down, and Sideways

There are several approaches to genealogy.

The first, and perhaps simplest it to go up. You start with yourself, then proceed to you parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, etc.

The next is to go down. You start with a known ancestor, and work you way down to their children, grandchildren, etc.

Another approach is what I call going sideways. This is usually called researching collateral lines. Simply, you are in most cases not the only descendant of the ancestors you are researching. If you want to research up to a great-grandfather or great-great-grandmother, your branch of the family may know something about them, but there may be many other descendants of those ancestors that know more. If you descend from the second child of your great-great-grandparents, what about those that descend from their first or third child? Do you know who all of your great-grandparents’ siblings were? Who were the children of those siblings? Finding out can help you find more distant relatives, and those relatives may know more than you do.

Another example is let’s say you want to know about your great-grandfather, but his daughter, your grandmother, has since passed, and your parents don’t know anything about him. Did your grandmother have siblings? Are any of them alive? If not, what about their children? Perhaps they know more about your great-grandfather than your parents know? Sometimes it happens that one branch of a family knows a lot more than another, either because that branch happened to get documents about the family (many times the oldest child), or because that branch lived physically closer to the great-grandparent, and thus spent more time with them.

This sideways research is an important strategy for finding information that you have no other way to find out. If the birthplace of your ancestor is not on any document, and only someone from a collateral branch of your family knows where that ancestor was born, then the only way to find that information is to figure out who these other relatives are, and to contact them. For more details on this research strategy, see my 2011 article Genealogy Basics: Up, Down and Sideways

The basic idea of this section is to get you to think about all the people that might know about your family. When you find someone who knows information, interview them. You can record a video of them, or an audio recording, or if you can’t visit them, try to get them to put as much in writing as you can. You can send them a form via e-mail and ask them to fill it out. If they have documents/photos but live too far away from you for you visit, see if they can scan them, or have someone help them to scan them. If you need to, offer to pay to either mail them back and forth, or pay for them to be scanned at a photo shop or print shop like FedEx Office (aka the stores formerly known as Kinko’s).

The importance of documents

As you reach out to family members and interview them, you should see what family documents they have, or know other relatives have. Are there birth certificates, ketubahs, passports, etc.? It’s important to find and scan everything you can, even if you don’t know yet what you’re going to do with them. As you build your tree you want to begin citing these documents as the sources of your information.

Think of it as building a legal case. Maybe you know the birth date of your great-grandfather because it was written on his gravestone. You can cite that as a source, although it is by definition a secondary source (i.e. the source was not contemporaneous with the event). Maybe your grandmother remembered the date as well and mentioned it when you were asking her about family. You can cite your interview with her as a second source (of course she may be the person who created the gravestone inscription, so this could be the same information). Now let’s say you find a social security application form that lists his birthday. As that application was likely filled out by him, that might be considered a better form of evidence. Maybe later you find his birth certificate. All of these pieces of evidence build the case for that piece of information. Some are more reliable than others. You want as many as you can find for each piece of information.

Once you’ve collected what you think you can get from family members, you can start looking online for documents. There are many places to look, some more obvious than others. Of course, the big commercial companies like Ancestry.com and MyHeritage.com have billions of records online, which you can pay annually to access. For research in the US, many sets of records can only be found in these commercial databases. Another amazing resources for records in the US is FamilySearch.org, which has billions of records that have been microfilmed and scanned over decades all across the globe. Not every document is available online, as some require you to access them within their network of Family History Centers, but if they’ve indexed the records then the indexes are usually online, even if the documents are not.

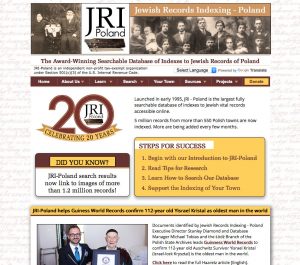

When looking for specifically Jewish records, there a few places to start your search, depending on where your family lived. For Poland the place to start is Jewish Records Indexing – Poland (usually shortened to JRI-Poland). JRI-Poland has indexed more than 5 million records from over 500 towns in Poland, and as the Polish State Archives have started to scan and make records available online, JRI-Poland has also started to link directly to the records from their index. You can additionally search JewishGen’s All Poland Database, which searches JRI-Poland’s database, as well as about 2 million other records split among a dozen other Poland databases on JewishGen, including business directories and Holocaust-related databases like their Yizkor Book Necrologies database.

When looking for specifically Jewish records, there a few places to start your search, depending on where your family lived. For Poland the place to start is Jewish Records Indexing – Poland (usually shortened to JRI-Poland). JRI-Poland has indexed more than 5 million records from over 500 towns in Poland, and as the Polish State Archives have started to scan and make records available online, JRI-Poland has also started to link directly to the records from their index. You can additionally search JewishGen’s All Poland Database, which searches JRI-Poland’s database, as well as about 2 million other records split among a dozen other Poland databases on JewishGen, including business directories and Holocaust-related databases like their Yizkor Book Necrologies database.

JewishGen also hosts many databases for other countries, including Austria, Belarus, Czech Republic, Canada, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and the United States. Other countries are also represented in various databases, but these represent the largest databases on JewishGen. Just a month ago JewishGen also launched a Unified Search that lets you search all of their databases at once, but this is still being worked on, and can be overwhelming to use if you search for a common name.

JewishGen also hosts many databases for other countries, including Austria, Belarus, Czech Republic, Canada, France, Germany, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and the United States. Other countries are also represented in various databases, but these represent the largest databases on JewishGen. Just a month ago JewishGen also launched a Unified Search that lets you search all of their databases at once, but this is still being worked on, and can be overwhelming to use if you search for a common name.

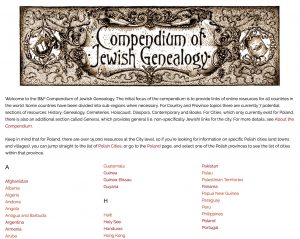

It’s worth pointing out that while you can go to JewishGen’s list of databases to see if there is database for the country your family comes from, you can also go to the page for that country in the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy on this site, and if JewishGen has a database for the country, it will be listed on the page for that country. For example, see the pages for Belarus and Ukraine. For Poland, there are resources for over 1400 towns with links to records in the Polish State Archives and on FamilySearch.

It’s worth pointing out that while you can go to JewishGen’s list of databases to see if there is database for the country your family comes from, you can also go to the page for that country in the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy on this site, and if JewishGen has a database for the country, it will be listed on the page for that country. For example, see the pages for Belarus and Ukraine. For Poland, there are resources for over 1400 towns with links to records in the Polish State Archives and on FamilySearch.

Of course not all Jewish genealogy-related documents are on JewishGen. Depending where your family is from there are many other sites with records. Some examples include Gesher Galicia, focusing on the former Austrian territory of Galicia, which is now mostly in Poland and Ukraine, and the Częstochowa-Radomsko Area Research Group, which covers hundreds of towns in Poland centered around Częstochowa. Another amazing site is Genteam.at, with over 18 million records for Austria, many of which are Jewish records.

To find sites for other areas, of course check the country listings in the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy. In those listings you can find independent sites for Jewish records from those countries, and even individual databases from larger sites such as FamilySearch or the USHMM. For examples, see a few of the many: Argentina, Austria, Jamaica, South Africa, and Ukraine.

For each document you find, you should add a citation for each piece of information you find to the people whom the record mentions. More on that below.

One more thing on this topic. As you find documents on your family, make sure to share them with your extended family. Finding a census record, passport application, naturalization petition, etc. and sharing those finds with other relatives is a great way to create interest among your family members, and encourage them to look through what they have and to contact family members you may not know. One way I’ve found useful in connected these extended groups of family is to create a Facebook group for descendants of a distant common ancestor couple. In a group you can configure it so any member can add other members. This is a great way to reach family members you may not have known about, and it gives you a simple way to share documents, photos and videos you find (and encourages other family members to do the same).

Organizing your research

When organizing your research, there are two main areas you need to think about, organizing physical documents and photographs, and organizing your digital files.

Let’s say you’ve located photographs from your grandparents, and after talking to them, or other relatives, you’ve managed to identify at least most of who are in the photographs. That’s great, but how do you make sure those photographs are going to be preserved for future generations?

Let’s say you’ve located photographs from your grandparents, and after talking to them, or other relatives, you’ve managed to identify at least most of who are in the photographs. That’s great, but how do you make sure those photographs are going to be preserved for future generations?

The first thing to do, when possible, is to remove everything from their old albums which are likely destroying your photographs. Old albums, especially those ‘magnetic’ albums where the photos stick to the backing, and are covered by a sheet of plastic, are filled with acid that eats away at your photos.

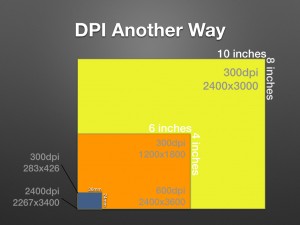

I’ve written some articles on this topic which are worth looking into for the details I can’t add to this one. Two worth reading are Preserving Photographic Prints, Slides and Negatives and What DPI should I scan my photos, and in what format do I save them?. I hope to post a video of my lecture on this topic soon as well.

Once you’ve organized and preserved your photographs and documents, you need to digitize them. Don’t put this off, as every photograph and every document will eventually fade. You can’t avoid that, but you can make permanent copies in their current condition by digitizing them. I won’t go into the details of how to scan photos and documents in this article. There are some details in the above article on DPI, but let me just say that storage is cheap these days, and you should scan at a minimum of 600dpi for any photograph, and more for smaller photographs, and keep copies of your files in at least two separate places. I keep my photos on at least two hard drives, and also upload them to cloud services like Amazon Prime Photos and Google Photos.

Once you’ve organized and preserved your photographs and documents, you need to digitize them. Don’t put this off, as every photograph and every document will eventually fade. You can’t avoid that, but you can make permanent copies in their current condition by digitizing them. I won’t go into the details of how to scan photos and documents in this article. There are some details in the above article on DPI, but let me just say that storage is cheap these days, and you should scan at a minimum of 600dpi for any photograph, and more for smaller photographs, and keep copies of your files in at least two separate places. I keep my photos on at least two hard drives, and also upload them to cloud services like Amazon Prime Photos and Google Photos.

Once you’ve scanned all those photos and documents, how do you organize them on your computer? This is a complicated issue. I have a system I use, outlined in Genealogy Folder Organization: The B&F System, which works well for me, although I use a Mac, and this may not work so well on Windows (which has restrictions on the full path length of file locations). I will say that I like to add the date of the photo or document in the beginning of the file or folder name, in the format YYYYMMDD (i.e. 20180815 for Aug 15, 2018), which makes it easy to sort files or folders chronologically. As an example, if I scan a newspaper article about someone, I might name the file something like: 20180815-NYTimes-MarriageOfMosheSmith.jpg. If I have a folder of newspaper articles, then this will allow me to sort them by date.

We’ve come a long way from when filenames were 8 uppercase characters with an extension of 3 letters (i.e. FILENAME.TXT). Use what’s available to add details. I also recommend using photo organizing applications that can add the relevant information on each photo to the embedded meta data. This allows the information on who and what is in a photo, where it was taken, when it was taken, etc. to be attached to the photo itself, which can later be read back using programs that support meta data.

So you’ve organized all the photos and documents you’ve been able to find from your family members, and scanned everything. All the photos that belong to you are now stored in archival sheets in binder boxes, and your scans are organized on your computer. What’s next? Obviously, you need to find more family.

Finding Family

Connecting to other researchers can be critical to one’s research, especially when one comes from an area that doesn’t have a lot of documentation. Sometimes you will also get lucky and find a cousin that has already done extensive research on your family, found lots of documents, collected lots of pictures, etc.

The first step in going online with Jewish genealogy is to register with JewishGen. JewishGen is a free site that has lots of information on Jewish genealogy, hosts the sites of many specialist Jewish genealogy groups (such as those focused on a specific region, or for example Rabbinic genealogy), and operates mailing lists for many of these groups. In addition, they operate the JewishGen Family Finder (JGFF) which helps researchers connect to each other by allowing researchers to submit surname/town pairs. Think about researching your name if it’s Cohen or Levy – not so easy. Think about researching Cohen or Levy who lived in a small shtetl with only a few hundred Jews, and it’s easier. Have an uncommon name, then you can search without the town name and see where your name pops up. It’s an amazing resource, especially for families that have lost touch with extended branches over the years, which is almost every family once you start looking.

The key to filling out your entries in JGFF is not to hold back. If you’ve done your research and filled out the forms, at this point you probably have a few names of towns your family lived in at one point (if not we’ll get to that), and you have surnames of family members, possibly even multiple surnames for the same families. Put it all in JGFF. You can put spelling variants, multiple names, towns your family just passed through, put everything in there. You never know if another person is going to be searching using exact spelling (which might exclude you if you used a different spelling – was the name Tanenbaum or Tannenbaum?), or if the other person may only know of the town your family passed through, and don’t know that. For example, if they asked their grandparent where they were from in Europe, and they told them the last town they lived in before coming to the US, they might have assumed that was where they were born, and not asked further.

I wrote a detailed look at how to fill out entries in the JGFF on the JewishGen blog some years ago, and while a little bit dated, it still works: JewishGen Basics: The JewishGen Family Finder (JGFF). I would just emphasize here that you should include your full name in your JGFF profile. It saves everyone a lot of time to see if they’ve corresponded with you in the past, and not to be morbid, but when JGFF researchers die it’s helpful to know who was researching your family, even if they are not currently living.

Once you’ve entered your own surname/town pairs, of course you should search in your towns to see if anyone is researching the same families, and search your name to see if the same towns occur that you’re familiar with. JGFF has a great feature that lets you contact other researchers even if they haven’t posted their name on the site. You fill out a form and they get an e-mail (assuming their e-mail hasn’t changed – let that be a reminder to keep your profile up to date with your most-current e-mail address – and don’t use a school or work address that might change).

Online Family Trees

The JGFF is not the only place you can make your research interests known. You can also post your whole family tree online, and make all or parts of it searchable. There are many sites where you can do this, although each has its own idiosyncrasies, advantages and disadvantages.

JewishGen has it’s own repository of family trees it calls the Family Tree of the Jewish People (FTJP) and Beit Hatfutsot in Israel has a similar repository (upload here, search here). The good news is that these two organizations have signed an agreement to create a shared search between both sites, which hopefully will be available soon. Both of these sites require you to have already created your family tree elsewhere and then export them into a standard file called a GEDCOM before you can upload your tree, so let’s take a step back.

When creating your family tree in digital form, you basically have two choices. You can use a program on your computer designed for creating family trees, or you can do so on a family tree web site. The largest commercial family tree web sites are run by the largest commercial genealogy companies, Ancestry and MyHeritage. Ancestry and Myheritage came to genealogy from different sides of the coin. Ancestry started with documents and added family trees. MyHeritage started with family trees and added documents. Both have now gone into the business of genetic genealogy. Ancestry is more US-focused (based in Utah) and MyHeritage has rolled up many European genealogy sites and is thus more international (based in Israel). The commercial sites have an advantage in that they can link people in their trees directly to the records they have on their site. Based on the information you add to your tree (name, birth date and location, names of spouse, parents, children, etc.) they search their databases in the background and make suggestions of possible record matches to people in your tree.

Ancestry allows one to set up family trees, and as far as I can tell they do not charge for this, but of course they will upsell you mercilessly to get one of their annual subscriptions that gives you access to their large collection of online documents (mostly US and UK records, with some other countries particularly Germany). Ancestry allows you to host multiple independent family trees, so you could have different trees for different sides of your family, or different versions of your tree that you can share with different people.

MyHeritage has two types of family trees online. Their main branded product is similar to Ancestry’s concept of self-contained family trees, although generally a person has one primary tree. You can, however, participate in other people trees. MyHeritage restricts you to 250 people in your tree on their free account, but they have paid subscriptions that allow 2500 people or an unlimited amount of people.

The second type of tree MyHeritage offers is on their Geni.com site, which they acquired in 2012. The concept of Geni is to build a single connected family tree for the whole world. Therefore, there are no self-contained trees, or concept of multiple trees for a single account. Everything you add to Geni is connected, and once you connect it to other people on the site, you join what they call the World Family Tree which currently has over 120 Million people in it.

Geni tries to get people to work on that one ever-expanding tree together. This is done in a number of interesting ways. Geni allows user to start projects around different research areas, allowing anyone to coordinate research around whatever they want. This could be descendants of a common ancestor, or people with roots in a particular geographic region, etc. In the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy on this site, there are currently links to over 150 Geni projects connected to countries and towns in the Compendium. To see which Jewish projects are on Geni, you can see the meta project Jewish Genealogy Portal, which points you to the other Jewish projects on the site. Another way Geni organizes research is around surnames. Both projects and surnames allow users to add information and start discussions with other users following those topics.

One other difference with Geni is the concept of Curators. Curators are experienced Geni users that volunteer to help others on Geni, and to manage complicated issues (including dealing with celebrity and controversial profiles on the site). There is a project outlining the Jewish Genealogy Curators, Curators who have experience with Jewish genealogy and can help you when you have problems on the site.

It’s a completely different concept, and some people love it (everyone working together to build a single tree), and some people hate it (usually because other people can change profiles you created, and sometime make mistakes). E. Randol Schoenberg has written in support of the Geni approach to genealogy which I recommend reading.

Besides the large commercial sites, there are many other family tree web sites online. Some are smaller commercial sites, some are free, and some are definitely better than others, but I would just caution that the most important thing to consider for one of the other sites is longevity. Plenty of family tree sites have simply disappeared over the years, and with them all the work people had done. Two that come immediately to mind are OneFamilyTree.com and AppleTree.com.

Another example worth mentioning was not strictly speaking a family tree site, but offers an important lesson. Ancestry once operated a social networking site for families to share information called MyFamily.com. When it launched in 1998 it signed up over a million registered users in under 5 months, but in 2014 after Ancestry.com and AncestryDNA had proven to be its more successful businesses, it dropped the site and its many users lost more than a decade of accumulated content. Ancestry allowed users to download an archive of their content, including photos and videos, but it turns out that the discussions between family members, the family stories that in many cases were the bulk of the content, was not included in those archives. Poof. Gone. Needless to say, there were a lot of incensed users. I don’t bring this up to bash Ancestry, but just to point out that even large sites may not be around forever, and you need to always have backups of whatever you place online, and you need to check that whatever site you are using has a way to download all of your data.

One free site which I recommend is WikiTree.com. Started by Chris Whitten, who also founded FAQ Farm (which sold to Answers.com and became WikiAnswers), it is a great family tree site that has been around for a long time. Most importantly, WikiTree.com has sophisticated privacy controls, has clear methods of saving your data, and has plans in place to protect your data. The site even has a pre-paid plan in place that insures it will keep running for 5 months in case the company goes bankrupt or otherwise cannot run the site, insuring the data will be retrievable.

The site is small compared to the above sites, with only about 17 million profiles, but amazingly, over 4 million of those profiles (over 20%) have DNA Test Connections. That doesn’t mean that there are over 4 million DNA tests connected to trees, but the site is smart enough to connect a Y-DNA test along the paternal line, and to connect an mtDNA test up the maternal line (and down from mothers to all children), etc. Another nice ‘feature’ of WikiTree is the effort on the site to create community among its users. One example is their annual Source-a-Thon, where they organize users into teams and compete to add the most sources to profiles on the site.

In the end, I don’t think there’s a huge difference between the major family tree sites, so find one you’re comfortable using, that has good and clear privacy controls, and insures your ability to keep your data backed up.

Working on your computer

Some people do all of their work using online trees, as described above. That works for some people, but just keep in mind that you should be regularly downloading copies of your tree to your computer to keep as a backup, and keeping copies of all your photos and documents well organized. One note concerning Geni in this case, which due to its nature has a somewhat more complicated method for downloading your tree. Since the tree is collaboratively built, you don’t necessarily add all your relatives, and you are connected to a tree of over 120 million people. Obviously it will not let you download 120 million profiles. Instead it lets you download 4 times the number of profiles that you’ve added, up to 5000 profiles for free users, and 50000 profiles for paid users. See their article How can I export my GEDCOM? about this issue.

Another way to keep things backed up is to actually build your tree on your computer, and only then add it to online sites. There are different ways to do this. Some programs are designed specifically to sync with online services, so you can moved changes back and forth between your online tree and your local tree. This is a nice feature to have if you want to be sure you have everything on your computer, but also want to benefit from the features of online trees (such as linking to documents and DNA functionality). Ancestry.com syncs with two genealogy programs, Family Tree Maker and RootsMagic. MyHeritage syncs with their own free Family Tree Builder program. MyHeritage recently bought Legacy Family Tree, another popular program, although it doesn’t (yet?) sync with MyHeritage.

Other programs can work with online services, but in general that is by exporting to a GEDCOM file (a file designed to transfer family tree information) and then uploading that file to the site. That will generally not include photos or documents, which would need to be added manually. Geni doesn’t allow uploading of GEDCOMS (they used to but they ended up with too many duplicate profiles), although you can use a browser tool called SmartCopy to build your tree on Geni based on an existing tree elsewhere.

Some popular programs besides those mentioned above include Family Historian (Windows only), Reunion and MacFamilyTree (both Mac only), and Heredis. One last program worth mentioning is GRAMPS, an open-source genealogy program. It is free, and will always be so. All of these programs can import and export GEDCOM files.

GEDCOM files are files that let you share genealogical information from one program or site to another. The format has not been updated in decades, however, so it has some severe limitations. As far as syncing between web sites and computer programs, those programs mentioned above certain use their own proprietary sync technologies for moving data back and forth, since they do more sophisticated things when syncing, including handling media (photos and documents) and sources better.

When working with other family members sharing GEDCOMs can be an important method of exchanging information, but be careful. Good genealogy programs will let you export a GEDCOM based on specific people, not the whole tree. If you have a tree with a thousand people in it, but only 50 of them are related to the person you want to share information with, you should only be sending them a GEDCOM with 50 people. Forgetting this can lead to all kinds of problems down the road where people are posting your family members information online even though they’re not related to them. This can happen anyways (and does) but thinking about what you send out is always a good idea, and can prevent conflict later.

I actually tend not to add GEDCOMs directly to my existing tree, but to open them in separate windows, and then comparing this with my tree and adding the people I don’t have. This allows me to check each person I add, check sources, make sure I agree with the conclusions that the person who shared their information with me came to, etc. It’s a lot more work, but it helps keep my tree sourced properly and verified.

Getting help

One thing that should be clear at this point is that pursuing your genealogy research is not a solitary pursuit. Besides working with your extended family members, there are tens of thousands of other people researching their families that are out there are willing to help.

One great resource are local genealogy societies. There are over 70 Jewish genealogy societies around the globe. Find the one closest to you and join. Some societies are also useful even if they’re not near you, as they may have information and experience with records of members of your family that lived in their area. Examples of such societies include the Israel Genealogy Research Association (IGRA) which has a database of over 1.25 million Israel-related records, and Jewish Genealogical Society of NY (JGSNY), which has many resources for genealogy in New York, where so many of our relatives lived. Of course, if your family lived in France, or Belgium, or Ohio, or California, there are societies in those places as well.

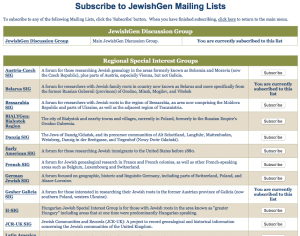

Another set of resources include the mailing lists available at JewishGen. Many of these lists are associated with specific regional research groups, such as Austria-Czech, Belarus or Latin America, while some cover specific topics such as DNA or Rabbinic Genealogy. Besides JewishGen, there are other sites that host Jewish genealogy mailing listings, including Rootsweb and Yahoo Groups, and I listed many of them in my article Jewish Genealogy Basics: Mailing Lists. That list is probably out of date, but even the non-active mailing lists can provide useful information in their archives. In particular the Rootsweb lists may or may not exist anymore, as they had a major outage at some point after I wrote that article, and they still haven’t fully recovered from it.

Another set of resources include the mailing lists available at JewishGen. Many of these lists are associated with specific regional research groups, such as Austria-Czech, Belarus or Latin America, while some cover specific topics such as DNA or Rabbinic Genealogy. Besides JewishGen, there are other sites that host Jewish genealogy mailing listings, including Rootsweb and Yahoo Groups, and I listed many of them in my article Jewish Genealogy Basics: Mailing Lists. That list is probably out of date, but even the non-active mailing lists can provide useful information in their archives. In particular the Rootsweb lists may or may not exist anymore, as they had a major outage at some point after I wrote that article, and they still haven’t fully recovered from it.

Lastly, I want to mention what is probably the most active area where you can get help. There are many active Facebook groups where Jewish genealogy is the center of discussion. Some are large general groups and some are focused on specific regions.  The largest Facebook group is Jewish Genealogy Portal with JewishGen, with over 28,000 members. The second largest is Tracing the Tribe, with over 25,000 members. Both have lots of experienced Jewish genealogists who are available to help with all kinds of questions related to Jewish genealogy. Need a document written in a language you don’t speak translated? Want to know what is says on a relatives’ gravestone but can’t read it? Need help figuring out what happened to specific relative, but don’t know where to look? Need someone with experience retrieving documents from Polish archives? or need help finding naturalization petitions filed in Missouri? Ask in these groups and you’ll be amazed at the answers you will receive. These two groups have slightly different philosophies on what they allow to be posted, but stay respectful and on-topic and you’ll find many people that can help you.

The largest Facebook group is Jewish Genealogy Portal with JewishGen, with over 28,000 members. The second largest is Tracing the Tribe, with over 25,000 members. Both have lots of experienced Jewish genealogists who are available to help with all kinds of questions related to Jewish genealogy. Need a document written in a language you don’t speak translated? Want to know what is says on a relatives’ gravestone but can’t read it? Need help figuring out what happened to specific relative, but don’t know where to look? Need someone with experience retrieving documents from Polish archives? or need help finding naturalization petitions filed in Missouri? Ask in these groups and you’ll be amazed at the answers you will receive. These two groups have slightly different philosophies on what they allow to be posted, but stay respectful and on-topic and you’ll find many people that can help you.

In addition to those mega-groups, there are more focused groups. Some examples include regional groups like Jewish Ancestry Poland, Jewish Genealogy Poland, Jewish Genealogy in Romanian Moldova, Jewish Roots in Ukraine, Jewish Jamaica Genealogy, and South Florida Jewish Genealogy. Many Jewish genealogy societies have their own Facebook pages to follow what is going on, and some have groups allowing discussion. In most cases, if there’s a Facebook group for a specific country, or a state in the US, you’ll find a link to it in the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy. If you know of one that isn’t listed, let me know and I’ll add it. For other genealogy topics, there are other groups such as Jewish DNA for Genetic Genealogy and Family Research and Jewish Rabbinic Genealogy – גנאולוגיה רבנית

Conclusion

I hope this article as a good introduction as to what one needs to get started in Jewish genealogy. There’s a lot to learn, and more than twenty five years after starting my own genealogy research, I’m still learning things all the time. The US Navy SEAL expression “Slow is smooth, and smooth and fast” comes to mind here. There’s a certain rush one experiences when finding new records, and adding new branches to your family tree, but don’t get so excited that you forget to record the sources for the information you add, and to double check everything you add to you tree.

There are many times I’ve seen two people conflated in a tree, such that one person had their children and the children of their cousin listed as their children, or someone split into himself and his uncle (i.e. the same name for two people, even though there is no evidence there were two people). I find examples of this in my early research from 25 years ago, where I added children to the wrong parent. With better access to some records today, I’ve been able to go back and correct mistakes I made before I documented my research as well. Imagine trying to figure out twenty five years on why someone is listed in your tree if you didn’t add a source explaining how you knew the information. Do yourself a favor and document every piece of information you add to your tree. You’ll thank yourself whenever you are reviewing your tree, whether next month, or decades from now.

So take it slow, reach out to family, collect sources, find photographs, and build a family tree that is an accurate representation of your family. Get your extended family involved, and use family tree building as a way to stay connected to distant branches of your family.

Thank for for all the information. I accidentally discovered this site in trying to find the English name translation (which is another story) and found a wealth of information to help me track down my ancestors.

Thank you. I’m glad the site is helpful.

This article is a treasure. Thank you!