This is the first in a series of articles on using DNA for genealogy. I’m going to start by taking a look at two types of DNA that are used in genetic genealogy, Y-DNA and mtDNA, and explain how they can be used by family researchers to help in finding relatives and in confirming relationships. A later post will look at autosomal DNA, and how this newer test can be both very useful, but less accurate as a genealogy tool. Keep in mind that nothing I will be discussing in these articles will relate to the issue of DNA testing for health reasons. While there are companies that do both genealogy and health related DNA tests, I will only be focusing on the genealogy side.

DNA Basics

Let’s start by explaining some of the basic terms and concepts of DNA, and DNA testing. As some may recall from high-school biology, humans each have 23 pairs of chromosomes. Twenty-two pairs of chromosomes are what we call autosomal chromosomes, and are inherited in equal part from both of a persons parents. In general, it is these 22 pairs of autosomal chromosomes that contain all the information that make up who you are physically – what color your hair is, what color your eyes are, how tall you are, what diseases you are pre-disposed to, etc. While interesting, most of this information is not particularly useful for genealogy purposes. The last pair of chromosomes are the sex chromosomes – two X chromosomes in a woman and an X and a Y chromosome in a man.

For the most part, the X chromosome is not very interesting from a genealogical point-of-view, or at least not any more interesting than autosomal chromosomes, since in women they are combined from each parent like autosomal chromosomes, and in men they get combined when passed on to daughters and are not passed on at all when the man has a son. Technically a man does receive the complete X chromosome from their mother, but this has limited genealogical value. From a genealogy point of view it’s best to ignore the X chromosome, or at least group it with autosomal chromosomes (which will be discussed in a future article).

Y-DNA Basics

The Y chromosome, unlike autosomal chromosomes, is only passed on from father to son, and is not modified at all. Thus if you are a man you have the exact same Y chromosome as your father, as your father’s father, etc. This is true going back many more generations, except that over time small mutations are introduced to the Y chromosome so eventually you will find a father who has essentially one character out of thousands that is different in the Y chromosome he has compared to his son. These mutations over time are what allow us to use the Y chromosome (or Y-DNA) for genealogical purposes.

If you find someone who has the exact same Y-DNA as you, then they are descended from a common male ancestor. Figuring out how far back that common ancestor is is where the mutations come in to play. If you find someone who has the same Y-DNA as you, except for one mutation, then you can assume the connection is further back than someone with no differences in their Y-DNA. If the person has two mutations, than the common male ancestor is even further back in time. By looking at the exact mutations, one can even figure out which people are in which branch of a family. For example, if you find three people with two mutations difference from your Y-DNA, and two of them share the one of the mutations, then you know it is likely that those two people descend from a common branch.

mtDNA Basics

You may have noticed that Y-DNA is only found in men. So how does one track their maternal line (mother to daughter)? The answer is not found in the 23 chromosome pairs of one’s DNA, but in the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is the DNA in the mitochondria of cells (essentially the engine of cells). Mitochondria, found in all cells, converts food in energy to power the operation of the individual cell. The mtDNA is the DNA of the mitochondria and is passed down from a mother to her children (both daughters and sons).

There are probably a few reasons that mtDNA is only passed from mother to child, and not from the father. The first reason is that the mtDNA of sperm is found in the tail section, and the tail breaks off during the fertilization process, and only the front section of the sperm makes it into the egg to fertilize (and contribute DNA). There have been some rare occasions where it has been shown that the entire sperm has made it into the egg, but in this case there are orders of magnitude more mtDNA molecules in the woman’s egg than there are in the sperm, so through dilution alone, the male’s mtDNA has little chance to have an effect.

Like Y-DNA, mtDNA mutates over time, and thus can be used for genealogical purposes. However, mtDNA mutates at a slower rate than Y-DNA, and thus a single mutation would push a common maternal ancestor back much further than a single Y-DNA mutation would push back a common paternal ancestor. This slower mutation rate makes mtDNA less useful for practical genealogy.

The Path of Y-DNA and mtDNA

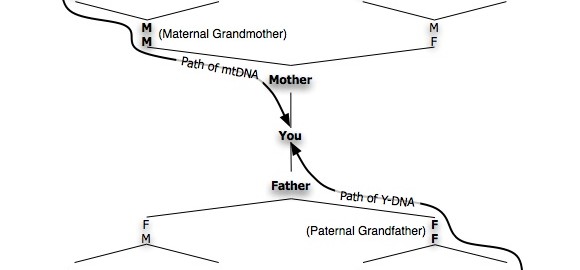

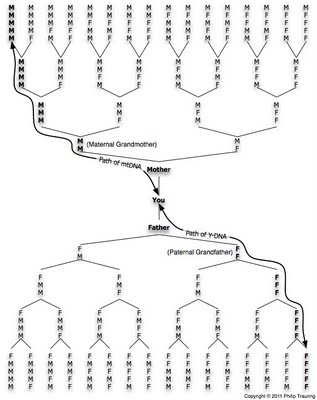

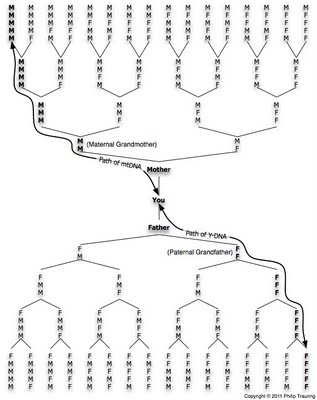

Thus, Y-DNA allows one to trace back direct paternal lineage (for men) and mtDNA allows one to track back direct maternal lineage (for both men and women). The following chart illustrates the path of Y-DNA and mtDNA inheritance (click to enlarge).

|

| The path of Y-DNA and mtDNA inheritance |

Note that out of thirty-one ancestors on each side of your family going back five generations (parent + 4 grandparents + 8 great-grandparents + 16 gg-grandparents) only five people on each side share the relevant DNA (i.e. mtDNA on your mother’s side, and Y-DNA on your father’s side) with you. Another way to look at this is that out of the 62 ancestors you have in the past five generations, only 5 match your Y-DNA and only 5 match your mtDNA.

That, of course, is only true when looking in one direction of your family tree (from you up). For example, you share the same mtDNA with all your siblings, as well as your mother’s siblings, your mother’s mother’s siblings, etc. and the children of all the women included among those people. Thus if your mother had a sister, then her children, your first cousins, would also share the same mtDNA that you have. If you find someone whose mother’s mother’s mother’s mother’s sister was your mother’s mother’s mother’s mother, you would also share the same mtDNA, even though you are fourth cousins. Of course, as mtDNA mutates slowly, you may share mtDNA with people much farther away as well, so sometimes this information is not so useful (and can be frustrating). The same is true of Y-DNA, except it is only in men, so if you are male you will match with your father’s brother’s son, but not with your father’s brother’s daughter since she has no Y-DNA to match, and not with your father’s sister’s son, since he inherited his Y-DNA from his father, not from his mother (which is your blood relative).

How Y-DNA is used for Genealogy

I’m going to start on the genealogy side by looking at Y-DNA because it has some significant advantages over mtDNA for using as a genealogical tool. First, as traditionally surnames were passed down from the father to his children, Y-DNA should in most cases match with people’s surnames. For example, just like your father’s father’s brother’s son’s Y-DNA should be the same as yours, so should his surname. This makes doing genealogy research using Y-DNA significantly easier.

Keep in mind that only men can take Y-DNA tests. If you are a woman and want to test your paternal line, you will need to have a male relative in the same paternal line take the test instead. For example, your father or brother could take the test, or your father’s brother, or your father’s brother’s son, or any number of other male relatives that are descendent father-to-son from a common paternal ancestor.

Another important point is that some people’s families only started using surnames in the past two hundred years (such as much of the Ashkenazi Jewish population) and you will find many different surnames that may match your Y-DNA since the matches (depending how close of a match) may have happened before two hundred years ago when your ancestor started using a surname. In fact, sometimes brothers in the same town were assigned different surnames (if they lived in different houses at the time surnames were assigned) and thus even if you find a close match that shares a common ancestor close to the time your family started using surnames, you might find a person with a different surname, and not realize how they are related.

This brings up an important point in using DNA for genealogy – DNA by itself will not build your family tree for you. Using DNA for genetic genealogy is just a supplement to traditional genealogy, and without pre-existing research of your family back to when there was a common ancestor, it won’t help very much.

So how does Y-DNA testing work? First, you take a DNA test from a company like FamilyTree DNA (FTDNA). I mention FTDNA in particular as they have the largest Y-DNA database. When doing any DNA test for genealogy, the results you get will depend on the number of people who have also tested and have their information in the company’s database. In other words, doing a DNA test for genealogy cannot tell you very much about yourself, but it can tell you about yourself in comparison to others.

FTDNA offers several levels of Y-DNA tests. They differentiate these tests by the number of ‘markers’ that are tested. Essentially, markers are locations on a person’s Y-DNA that are prone to mutation. By comparing these markers and seeing how many are different, you can figure out how closely someone is related to you. Y-DNA tests that FTDNA offers, or has offered, include 12, 25, 37, 67 and 111 marker tests. Each test with more markers allows more accuracy in predicting relationships between people. At the 12-marker level, for example, even an exact match on all 12 markers will only indicate a common ancestors thousands of years ago. This is beyond the ‘genealogical time frame’ – i.e. it is beyond the point that anyone would be able to trace back their family trees and is thus essentially useless for genealogy purposes. Of course, your father and your father’s father will all match you on all 12 markers, so while a 12 marker test cannot be used to show any kind of useful family connection, it can be use to disprove a family connection. For example, if you are a man and you find another man who you think is related to you on your paternal line, if your 12 marker test shows different results than the other man, then you are not likely related on your paternal line. Thus even a 12 marker test has some usefulness, but it is limited to disproving theories, not proving anything.

For genealogy, if you are planning to do a Y-DNA test, you really need to start with at least (at FTDNA) their 37 marker test. FTDNA estimates that when you find someone with the same surname as you and who has a full 37 marker match on the 37 marker test, that there is a 95% chance of a common male ancestor within 8 generations and a 50% chance of there being a common ancestor within 5 generations. Of course, these odds may not sound too good to you. Even if you have tracked your family back 8 generations, the other person who matches you on your test may not have done enough research to make a connection. With a common surname and an exact match on all 67 markers of a 67 marker test, FTDNA estimates a 90% chance of a common ancestor within 5 generation and a 50% chance of a common ancestor within 3 generations. That said, these percentages assume that all the markers match. For example, if only 66 out of 67 markers match on a 67 marker test, then the common ancestor is pushed back further in time.

Of course, each level of test with more markers is more expensive than one with less markers. One good thing about FTDNA is that they bank your DNA samples so if you, for example, buy a 37 marker Y-DNA test and later decide to upgrade to a 67 marker test, you can just order the upgrade online and they will retrieve your existing DNA sample and run the new test. You can thus spend less at the beginning, and if you find that you get a lot of 37-marker matches and want to get the 67 marker test (or even the 111 marker test) to help you refine your results, you can always do that later.

Once you have the test done, you get a few things from the company.

First, you get a list of the marker values. If you got a 37 marker test, then you’ll receive a list of 37 marker values. These numbers are what get matched to others.

FTDNA will also estimate your haplogroup. Your haplogroup is a very broad designation of your ancestral origins. Essentially it means you match a common ancestor tens of thousands of years ago. This is not particularly useful from a genealogy point of view, but it can tell you something about where your very distant ancestors lived. You may have noticed I said FTDNA will estimate your haplogroup.The reason it is an estimate is that a Y-DNA test tests STR mutations and you need to test SNP mutations to really confirm one’s specific haplogroup. I’m not going to go into the differences between STR and SNP mutations in this article, but FTDNA can predict your haplogroup based on how other people in its database have matched, and if they can’t they will run SNP tests to confirm their result. If you want even more specificity in your haplogroup results (and sub-group results) you can also pay for what they call a Deep Clade test, which will confirm your haplogroup using SNP tests. None of this is particularly useful for practical genealogy.

In addition to your marker results and your haplogroup, FTDNA gives you what they call ‘ancestral origins’. This is a list of where other people who closely match you have indicated their family originated. This is largely dependent on the information people provide on their family, and how far back people have researched their families. This can give you some areas to research, but again it is based on what other people know about their own families, which is not always accurate.

Your Y-DNA Matches

Lastly, and most importantly, you receive a list of matches. FTDNA will compare your Y-DNA markers to all the results in their database and give you a list of matches. They start by showing you a list of all the 12 marker matches. If you have an Ashkenazi Jewish background, expect hundreds or thousands of matches at this level. As mentioned, at this level your matches have little meaning from a genealogical point of view since the match could be thousands of years in the past. FTDNA then proceeds to show 25 marker matches (I believe 25 marker tests were offered in the past and later replaced by the 37 marker test), 37 marker matches, 67 marker matches, etc. Obviously you will only see results up to the level you have had tested.

Keep in mind that if you receive a match at 25 markers and you don’t see the same person listed in your 37 marker results there are two possible reasons for this:

The first reason is that the person matched at 25 markers but mismatched on many of the 12 additional markers in the 37 marker test and therefore no longer shows up as a match.

The second reason that someone might not show up in the 37 marker results is that they never had more than 25 markers tested. They might actually match you completely at 37 or even 67 markers, but you won’t know unless they upgrade to more markers. In this case, if you find someone at a lower marker level that you think might be a match (for example because they share your surname, or they originate from the same ancestral town) then you can try asking them to upgrade their test.

Because FTDNA is completely focused on genealogy, and does not offer health information, the assumption when you sign up is that you want to be in touch with people to research your families. In fact, when you take your initial test (by scrubbing your cheek with three swabs and mailing them in) you will also sign a release form that allows them to share your e-mail address with other matches. Other companies like 23andMe which does health testing also, have double-blind communication systems that let one communicate with someone anonymously initially, share just genealogically relevant data and then share health information later if you choose. As long as you sign the release form when you send in your DNA sample, FTDNA eliminates this extra step and just provides you with e-mail addresses of your matches. If you don’t want matches to know your real e-mail address, you can always set up a dedicated e-mail address on gmail or similar service to communicate with matches on FTDNA.

In addition to the exact matches, the list includes matches that are one or more markers off from the total. For example, if there is a 12 marker match that matches 11 exactly, and the twelfth match is one value off, then it will show up as a 12 marker match with a genetic distance of 1. If another genome matches yours on 35 out of 37 markers, and the other two markers have values that differ from yours by one each, then it will show up as a 37 marker match with a genetic distance of 2. However, if the same genome was tested at 67 markers and matches all the other 30 markers, then it would instead show up as a 67 marker match with a genetic distance of two. As you move up in the number of markers you will continue to have fewer and fewer matches, as it becomes less and less likely you will receive a match. You may have hundreds of matches at the 12 marker level, dozens of matches at the 37 marker level and only a few matches at the 67 marker level, none of which may be exact matches.

All of this may seem abstract, so let’s take a look at what matches look like (click to enlarge):

|

| Some Y-DNA matches |

In the screenshot you see a selection in the middle of my results. You see all (four) of my exact matches at 37 markers (names and e-mail addresses are blurred). You can also see that there are nine 37 marker matches that are a genetic distance of one (although only the first two are shown in the screenshot). Other things to notice are that those matches that have tested at 67 markers, show that in parenthesis next to the match’s name, so the last exact 37 marker match and the 2nd 37 marker match with a genetic distance of one, both show they have been tested with 67 markers.

You can also see that there are one or two icons on the right side of each match line. The first one which all of the matches show is what FTDNA calls the FTDNATIP. This is FTDNA’s projection of how closely the match is related to you. For a 12 marker exact match, for example, it would show you that the person has a 33.57% chance of sharing a common ancestor within 4 generations, a 55.88% chance of sharing a common ancestor within 8 generations, and a 94.80% chance of a common ancestor within 28 generations. Like mentioned before, 12 marker matches are not easy to work with for genealogy since the matches can be so distant. By the 37 marker exact matches, the chance of a common ancestor within 4 generations jumps to 83.49% and 97.28% within 8 generations. I can’t tell you what the chances of a common ancestor are for exact 67 marker matches since I don’t have any, but I can tell you that the 67 marker match at a genetic distance of one has lower probabilities than an exact 37 marker match.

Oddly, FTDNA doesn’t check to see if a match shows up in higher marker tests when showing these calculations, so it will show a higher probability for the same match when showing it as an exact 37 marker match than it does if it later shows up as a 67 marker match at a genetic distance of one.

The second icon with an FT in the middle, which only shows up in two of the matches in the image, indicates the person has uploaded a GEDCOM of their paternal family tree. A GEDCOM is a standard file that most genealogy programs support that contains information on who is in your family tree and how they are related. FTDNA allows you you upload a different GEDCOM for your paternal family tree (for Y-DNA matches) and for your maternal family tree (for your mtDNA matches) so that other people can view the relevant family tree and try to find relatives or at least family names in common. If the person has uploaded the relevant GEDCOM file then the icon will show up on the right side of their match and allow you to view it.

An interesting point to make here is that out of the four exact 37 marker matches, only one of them has been tested at 67 markers. This means only one match has the possibility of showing up as an exact 67 marker match in my results. In fact, that match shows up as a 67 marker match with a genetic distance of one, which means of the extra 30 markers in the 67 marker test, one of the markers is off by one value. It is possible that the other three exact 37 marker matches could be exact 67 marker matches, but without them upgrading their tests to 67 markers, there is no way to know. However, keep in mind that if you only look at the 67 marker matches, then you might miss out on these three matches which may actually be closer relatives than the one of the four which shows up in the 67 marker results.

How mtDNA is used for Genealogy

As discussed, mtDNA tracks one’s maternal line, so it shows you matches from mother to child. Both men and women can take this test, since all children receive their mother’s mtDNA. When you take an mtDNA test, you can use the higher-resolution tests to try to find common maternal ancestors, or you can use it to disprove a theory if you think someone shares a common maternal ancestor.

Instead of marker values like Y-DNA, mtDNA gives you the differences between your results and the CRS (Cambridge Standard Reference). The CRS is the mtDNA whose sequence all other mtDNA results are compared to, and since mtDNA mutates so slowly, the changes are not usually so large. For example, at the lowest resolution (the mtDNA test of the HVR1 region) I only differ from the CRS in two locations. In the high resolution results (the mtDNA Plus test of both HVR1 and HVR2 regions) I differ in seven locations. In the full sequence (the mtFullSequence test of the entire mtDNA genetic sequence) I differ in only 13 locations from the CRS. It is these differences which are compared to others in the database when looking for matches.

FTDNA will also assign you a maternal haplogroup and show you your ancestral origins for your mtDNA.

Your mtDNA Matches

Matches to your mtDNA work similarly to your Y-DNA matches, so I won’t go into every detail, but I will explain the differences.

First, there are three levels of mtDNA matches available through FTDNA. Most other companies that provide mtDNA testing offer at least the first two. At FTDNA these testing levels are called mtDNA, mtDNA Plus and mtFullSequence. The mtDNA test tests a region of mtDNA called HVR1. The mtDNA Plus test also tests the region called HVR1 but adds a region called HVR2. This added region, like additional markers on the Y-DNA test, increases the likelihood that matches are closer related. mtDNA comprises a much smaller amount of DNA than Y-DNA or certainly all of autosomal DNA, so FTDNA offers a third option, called mtFullSequence, which tests all of the mtDNA strand.

When viewing matches, they are shown in three categories which correspond to the three testing levels: Low Resolution (HVR1), High Resolution (HVR1 + HVR2) and Full Genomic Sequence. Like in Y-DNA matches, when a match has tested at a higher level it will show when viewing the match at what level the person has tested. For example, when viewing the Low Resolution matches, if a match has taken the mtDNA Plus test, then the match will show in parenthesis next to the name HVR2. If the match has tested with the myFullSequence test, then it will show FGS next to the name. If the match also has tested in Family Finder (FTDNA’s autosomal test which I will discuss in a future article) it will also indicate this next to the name.

If the person has uploaded a GEDCOM file of their maternal line, then a icon (with the letters FT) will indicate this, and clicking on it will show you the person’s maternal family tree (thus the FT).

Like with Y-DNA matches you are show their actual e-mail addresses and you must contact your matches directly in order to find a connection. Finding mtDNA matches is harder than Y-DNA matches since the mutation rate is slower, the connections are generally farther back, and the matches have no correlation to one’s surname. If one family had five daughters three hundred years ago and you are descendant from one of the five daughters, think how many family names each of the five daughters descendents have gone through in the intervening years. It is very difficult to track these kinds of connections.

Conclusion

Genetic testing is an interesting supplement to traditional genealogy, and can connect you to many potential relatives when doing research on your family. It is not a replacement for doing real genealogical research, but can help you confirm or disprove theories of how people are related, and can connect you to many potential relatives that may know of branches of your family that you are unaware. The same tests can also provide health information, genetic traits, ancient origins, etc. but these are not useful for genealogy. While genetic testing can be expensive, the cost is continually going down as more and more people try it out. As more people test, the databases in which one is comparing their DNA to others is also getting larger and larger, making them more and more useful. Genetic genealogy is only ten years old, so as more and more time goes on, it will become more and more useful, more and more accurate, and more people will be able to find real matches to relatives using genetics as their roadmap.