When you do research into your family, you need to cite your sources. Without sources for all the names, dates, etc. that you put into your family tree, your tree doesn’t really mean that much. Let me explain why this is the case.

There are millions of people worldwide who are actively researching their family trees. Some people consider it an occasional hobby, and others spend all their waking days looking into their families. No matter which side a researcher finds themselves on, or anywhere in between, the quality of the research done by these people varies greatly. In other words, some people do quality research, back up everything they find, and cite the sources for everything so they can go back and tell you how they determined the year a particular person was born, or what their name was before immigrating to the US, etc. Other people do lower-quality research, don’t record where they found anything, and just enter the names and dates they find into a database on their computer, or directly to an online family tree. I would venture to guess that there is little correlation between how much time someone spends on their family tree, and whether people are quality researchers or just name collectors.

So why is it a problem to just collect names and dates and throw them into a database? Well, primarily the problem is that you will make mistakes. I don’t mean that quality researchers don’t make mistakes and sloppy researchers do make mistakes – I mean everyone makes mistakes. There will always be times when you find a record of a person and you think it is the brother of so-and-so or the father of this-or-that cousin, and it really isn’t.

A good researcher will cite the source for the record, and most likely recognize that without more information they cannot conclusively say that the person is who they think it is. The good researcher might not even put the person into their tree, but put them in a folder for unconfirmed relatives until such time that they do find more information. If you don’t cite where you found out a piece of information, then when you do find more information, you will have no way to compare your new information with the old information.

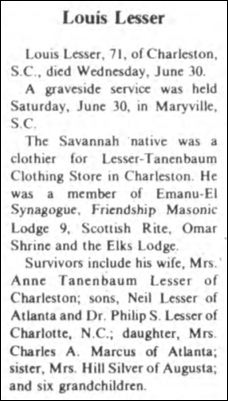

For example, if you first calculated the birth year of a person by their age listed on their grave, but later find another record with the birth year on it, how will you know the relative strength of the new record versus the old record in terms of determining the birth year. Will you remember ten years later that you determined the age from a gravestone? What happens if you ended up recording the age of the wrong person? How would you confirm that without knowing your original source? Maybe you recorded the name of the person’s niece of nephew that shared the same name. How would you be able to tell?

Imagine a researcher just records names and dates as they find them. They don’t double-check anything, and couldn’t if they tried since they don’t know where their information originated. Using an example where someone recorded a nephew instead of the uncle, let’s say that same person finds a tree of the nephew online (which they identify since the spouse is the same). They copy and paste the new information into their tree, except it’s under the uncle instead. Now you have a branch of the family which is completely wrong. What does this researcher do next? They post their tree online with no sources. The next person comes along and finds someone who matches in their tree and copies the rest of the tree into their own, propagating the mistake.

There are really two lessons to be learned here.

First, don’t trust anything you find on the Internet, without independent confirmation. If you import a tree from a web site, make sure to check it out first.

Second, cite the source for everything you record in your own family tree, so you won’t come back years later with a new, different, piece of information and not know which is correct.

How To Cite Sources

When you were in high school or college you probably remember having to format your sources according to a citation style guide like the Chicago Manual of Style or the MLA Handbook. These guides defined where the title of the book or article went, how the author’s name was listed, etc. with examples for different types of citations – like newspaper articles, published books, unpublished dissertations, etc.

In the world of genealogy, there are many more types of evidence that one might need to cite in their research, since a scribble on the back of a an old photo, a listing in a commercial online database, the inscription of a gravestone, vital records of all kinds from all countries, etc. can be cited – all for the same person. The bible of genealogical citation is Elizabeth Shown Mill’s Evidence Explained. The book contains over a thousand citation models for just about any source you can think of that you will come across in your genealogy research. For example, do you know how to cite this blog entry? According to Evidence Explained (pg. 812) it could be formatted something like this:

It gives a two more options for different types of blog citations. It also has citation models for tweets, chats, discussion forums, podcasts and other Internet-based content that probably wasn’t listed in the MFA Handbook or Chicago Manual of Style the last time you used one of them. I’m pretty sure that even today you won’t find a citation model for citing a gravestones in the Chicago Manual of Style. Coming in at over 800+ pages, Evidence Explained is a much bigger book than those other style guides.

There has been an effort by some to try to standardize genealogy citation models around those in Evidence Explained, and indeed some genealogy software programs have offered the ability to use Evidence Explained citation models when citing sources in your program. I think that it’s good to have a standard for citations, and I hope all the major genealogy software companies adopt Evidence Explained as their citation model. If there isn’t a standard for citations, then sharing citation between programs becomes difficult.

The Debate

While there is no debate in the world of genealogy that there is a need to cite sources, there is a big debate over how to cite sources. Do you really need to follow strict citation standards like those advocated by Evidence Explained? Therein lies the issue debated amongst genealogists, how important is it really to use a citation model? Isn’t it just important to convey the information to find the source cited? Do you really need to follow an 800+ page book explaining every possible citation model you could need?

I’m not going to go into this debate in depth. I’m simply going to give my opinion that as long as you convey the correct information in an understandable way, the style is not really important. I think it’s great to use a system like Evidence Explained if you can, but if there’s a chance you won’t enter the source because it takes too long to figure out the right citation model for the source and you think you’ll get back to it later (which you won’t) then just enter the citation however you want. As genealogy programs add better source citation tools, this won’t become as big an issue and it will actually be easier to cite them properly when it is automated.