A recent tweet by Leland Meitzler caught my eye, linking to a post on his blog GenealogyBlog.com, that referenced an article by Allison Carter about researching roots in Newton, MA. I grew up in the town next to Newton, so I thought it would be interesting to see what the article was talking about. My family didn’t move to Massacusetts until the 1960s, so there was unlikely to be anything directly related to my family, but I’m always curious about new resources available online.

The article mentions that the City of Newton recently posted birth, marriage and death records, as well as city directories, online. The city scanned these documents and has made them available as PDF files on a new Genealogy page on their web site. They have birth, marriage and death records from 1635 up until 1899, and city directories from 1868 up until 1934. They say more will be added in the future. It’s nice to see a city making these records available to the public and I hope more communities will follow suit.

As I looked at the most recent City Directory from 1934 it occurred to me that as a researcher looking for Jewish ancestors, I was unlikely to find much from that far back. While Newton today has a large Jewish population, I don’t believe it had very much at all in the 1930s, and certainly not earlier. That made me think about the communities in the Boston area that had earlier Jewish populations – places like Lowell, Roxbury and Dorchester. Did these communities have records online? Like in many cities, Boston’s Jewish community had over the years started in the urban and industrial centers and moved out to the suburbs. This process is still continuing today.

As I looked at the most recent City Directory from 1934 it occurred to me that as a researcher looking for Jewish ancestors, I was unlikely to find much from that far back. While Newton today has a large Jewish population, I don’t believe it had very much at all in the 1930s, and certainly not earlier. That made me think about the communities in the Boston area that had earlier Jewish populations – places like Lowell, Roxbury and Dorchester. Did these communities have records online? Like in many cities, Boston’s Jewish community had over the years started in the urban and industrial centers and moved out to the suburbs. This process is still continuing today.

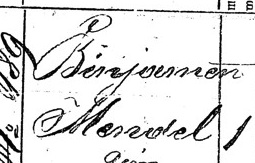

I first searched for Lowell, as I know a family that has a long history there, and wanted to see if they would show up in any records. Some searching online turned up a Genealogy Resources page on a site run by the Center for Lowell History at the University of Massachusetts. One of the pages listed in the resources is Lowell – Vital Records 1865-1970. From there, there are pages for Births, Marriage Intentions and Deaths. Each one of those pages lets you look at the transcribed records (not the originals), but you need to know the year in order to find the record. There is no search. That can be fixed with a little help from Google of course. Searching Google for:

site:http://library.uml.edu/ SURNAME

will search the entire web site for the surname I specify (add site: before the web site URL, a space, and then the keyword(s) you are searching for). Indeed running this search on the surname of the family I was searching for found a page from the Marriage Intentions section in 1947 showing a couple I once knew, including the maiden name of the wife and the issue of the newspaper in which it was published. The page indicates that the index was created from marriage announcements in the Lowell Sunday Telegram, a newspaper that ceased publishing in 1952 (it was bought out by a competitor). One can go to the UMass library in Lowell and access these newspapers to see the original citation, but I was curious if the newspaper was available online.

GenealogyBank.com, which I’ve written about before, has thousands of newspapers online. I looked at their title list and while they list three other Lowell newspapers (all published in the 19th century), they do not have the Lowell Sunday Telegram.

I then checked out Chronicling America, a project to digitize historical newspapers run by the Library of Congress, but it appears they do not have any newspapers from Massachusetts (yet). They do, however, point to the fact that the Boston Public Library holds copies of the Lowell Sunday Telegram on both microfilm and in the original. Hopefully either GenealogyBank or Chronicling America will get around to scanning the Lowell Sunday Telegram one day. At least we know it is preserved in at least two libraries, and is on microfilm.

So what about the other towns in Massachusetts that had early Jewish communities? I can’t say I’ve been as lucky there in finding records. The flight of Jews from communities like Dorchester, Roxbury and Mattapan is well documented. One book which looks interesting (although I have not read) on this topic is The Death of an American Jewish Community: A Tragedy of Good Intentions which focuses specifically on these communities and was co-written by the former editor of The Jewish Advocate, Boston’s largest Jewish newspaper. The Jewish Advocate has been published since 1902 and their archives would certainly be important for anyone researching Jews in the Boston area for the past century. The Jewish Advocate actually does have an online archive, although it only has issues dating back to 1991, which means it is not very useful for researching these former major Jewish communities. JewishGen, however, does offer a Boston obituary database from 1905 to 2008 gleaned from the Jewish Advocate.

Another approach to researching these communities is to find people in the JewishGen Family Finder (JGFF). Most people think of the JGFF as only covering communities overseas, but you can add records to the database for any community, and indeed Dorchester, Lowell, Mattapan and Roxbury all have entries in the JGFF. See my earlier article on the JGFF if you’re not familiar with how it works.

So what’s the moral of this story? Especially if you have no Jewish roots and you just trudged through this article and the Jewish part doesn’t apply to your research? There are a lot of local resources available, if you spend the time to look for them. Other sites like USGenWeb can be useful in tracking down local records, as are specific sites like DeathIndexes.com, but in the end a bit of time and effort searching for the town you want to find records in is the best idea, as you never know where you might find them. The big record database sites like FamilySearch.org and Ancestry.com are great, but sometimes the tiniest local site might actually have what you’re looking for…