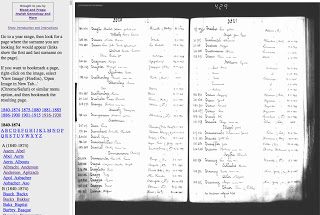

This is a quick post while I am still preparing for my lecture at the IAJGS Int’l Jewish Genealogy Conference next week, but it’s something I hope to write more about in the future.

When Jewish immigrants arrived on US shores in the late 19th century and early 20th century, they formed mutual-aid societies, usually based on the town or region they came from ‘in the old country’. These societies are called Landsmanshaftn (Landsmanshaft is the singular form of the word). You may have heard of the term landsman meaning someone from the same place as you. Thousands of these organizations existed. In addition to helping new immigrants get on their feet in their new country, one of the major functions of many of the societies was to organize burial plots for its members. This is an important point for those people researching Jewish immigrants from this period, as Jews from this period would most likely have joined one of these societies, and would have bought a plot to be buried in within sections owned by their Landsmanshaft. If you don’t know where your immigrant ancestor was from, but can find their grave, you might be able to figure out where they’re from just from the section in which they’re buried.

While the Landsmanshaft societies thrived during the years around the turn of the century, they largely died out as their members died off and their children born in the US didn’t need the services provided by the organizations. In some cases this actually led to serious problems as member had purchased rights to a plot in the society’s cemetery section, but the people needed to approve their burial in the cemetery had died off before them and not left things in the hands of someone who could handle it. A NY Times article from 2009 covers this problem of societies disappearing before all their members have been buried in their cemetery sections.

For many of these societies, as their final members died off, the remaining officers donated their records to the YIVO Institute. For thousands of other societies, however, their records were unfortunately lost to time, probably thrown out by children or grandchildren of the last keeper of the societies’ records after the person’s death. Some societies still exist in one form or another, and hopefully they will donate their records to YIVO or another suitable archive for preservation.

Washington Cemetery

A few weeks ago I visited Washington Cemetery in Brooklyn. This is a massive Jewish cemetery in the Midwood section of Brooklyn. The cemetery actually made the news several times in the past year. First there was the likely hate-inspired vandalizing of graves (photos) there back in December. In January, it was city sanitation workers’ turn to damage dozens of graves when they dumped snow into the graveyard during blizzard cleanup and knocked over a fence and many gravestones.

An article from July about using lasers to etch portraits on gravestones used Washington Cemetery as the centerpiece of the article. Indeed when visiting the cemetery one could not miss the very large number of laser-engraved gravestones, particularly because it appears the cemetery seems to have been putting new graves into places that were not previously intended for graves, like along walkways in front cemetery sections. Thus the first graves you see whenever you are walking along the cemetery are these newer graves (largely from Russian Jews who immigrated to the US much more recently than the majority of the people buried in the cemetery). That the cemetery has been forced to put graves into any open spaces might explain the recently controversy over the graveyard’s desire to buy a residential property to expand (interesting note from the article – no NYC city graveyard has ever expanded since they started keeping records in 1948).

I had a note in my tree written by a relative (that I had imported years ago) that mentioned my gg-grandparents were buried in Washington Cemetery. I only vaguely remembered that note when I read about the damage back in January, but I looked up the note in my tree and called the cemetery to figure out where my gg-grandparents graves were located, and if they had been affected by the vandalism or snow-damage. Luckily my gg-grandparents’ graves were located in a section not affected by either problem. When I arrived in NY for the first time since that time a few weeks ago I decided to see if I could find the graves. As I followed the directions given to me from a woman in the main office of the cemetery, I came upon this:

|

| Entrance to section of cemetery in Washington Cemetery |

There are a couple of interesting things to notice in this picture.

First, if you read the article I linked to above about laser-etching gravestones, you’ll notice the black granite gravestones in the front of the cemetery section are all laser-engraved. You will also notice that they are not actually in a cemetery section, but rather in the buffer space in between the cemetery section and the walkway. Thus those newer gravestones have nothing to do with the section immediately behind them.

Second, you should notice the elaborate stone arch with the metal gate that forms the entrance to the section. Not every section in the cemetery have such entrances. As this section is the one where my gg-grandparents are buried, I was interested to see what was inscribed on the arch, and what it might tell me about where my gg-grandparents originated. Keep in mind that just because someone is buried in a cemetery section managed by a Landsmanshaft doesn’t necessarily mean that the person was from the town around which the Landsmanshaft was formed (especially spouses) but it is one more clue to add you your research into where your immigrant ancestor originated.

So what does the gate say? Here’s a closer look:

|

| Independent First Odessa Sick & Benevolent Association cemetery section |

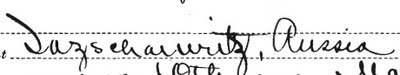

The arch reads: Independent First Odessa Sick & Benevolent Association (I’ll shorten that to IFOSBA). Along the sides of the stone arch are the names of the people who organized the purchase of the cemetery section for the Landsmanshaft. If you look into Landsmanshaftn, you’ll notice almost all the words used repeat in other organization names. ‘Independent’ might be a break-away organization, ‘First’ is very common – so common I really wonder if they were really all first, and if Independent did mean it broke away from another organization then how can it also be First? I don’t know the answers to these questions, but to get an idea of how many organizations there were of this type, see this list created by the Jewish Genealogical Society of NY (JGSNY) of the collection of Landsmanshaftn records held by YIVO.

Another list created by the JGSNY is that of Landsmanshaftn incorporations in NYC, which were microfilmed by the American Jewish Historical Society (AJHS). These documents are what was filed by the societies when they formally incorporated in New York. The documents are generally signed by the founding officers of the organization, and can list their addresses at the time as well. While these are single documents without extensive information on the members of the organization, they can still be useful. I requested a copy of one such document on the First Kancziger Aid Society, a Landsmanshaft for people from Kanczuga, and found that another gg-grandfather of mine and his brother were both founders of the organization, and the document had their signatures and their home addresses. It turns out that while YIVO doesn’t have records on either the First Kancziger Aid Society, nor the IFOSBA, the AJHS has incorporation documents for both societies. I hope to get a copy of the incorporation document for the IFOSBA soon to see what I can find out.

Back to the Cemetery

So, it’s not particularly relevent to the rest of the article, but I thought I would mention that I did indeed find the graves of my gg-grandparents in this section:

|

| Gravestone of my gg-grandfather, Sam Greenberg |

|

| Gravestone of my gg-grandmother, Gittel Greenberg |

Vandalism

Note that on the top of the stone of my gg-grandfather there was an embedded portrait (same size and shape as the one on my gg-grandmother’s) which was ripped off the grave. Not sure who would want to do that, but as mentioned earlier in the article, this cemetery has seen its share of vandalism. Indeed in the same small section there were several gravestones that had been knocked over:

It is sad to see such vandalism in a cemetery. I’m not sure what to think about the fact that the cemetery administration doesn’t re-cement the stones. I can understand that in cases where the stones are broken and require extensive and expensive repairs that the cemetery may seek to have the costs covered by relatives if they can be found, but in the case of something like this in an urban cemetery, I would think putting them back up and re-cementing them would be a routine part of their regular maintenance.

A Final Note

If you’ve exhausted all methods of figuring out where your immigrant ancestor came from, and you know where your ancestor is buried, you should look into which section your ancestor is buried in in the cemetery. Even if there is no grand entrance to the section, it should be marked. If the section is not marked, the cemetery office should know who purchased the section and can tell you if there is an active organization managing it or not. From there, tracking down documents from the Landsmanshaft from YIVO or the AJHS might be a good next step to finding out more.

See a short follow-up to this article, More on Landsmanshaftn about retrieving society incorporation documents from the AJHS.