…find a grave. Well yes, you can carry out FindAGrave.com‘s namesake function and find graves online, but there is a lot more to the site as well. During the fifteen years or so that I’ve done genealogy I’ve come across the site many times, but I have to admit I never really gave it a close look until recently. Once I had taken a look, I was surprised that many people I know who are involved in genealogy had also never really taken a close look at the site.

That’s not to say the site is not popular. In fact, according to compete.com, a web analytics company, FindAGrave.com has had more unique users in the past year than FamilySearch – over one million unique users in fact. Of course, neither site is close to Ancestry.com’s traffic, but that’s not really a fair comparison.

|

| Unique visitors over past 13 months to Ancestry, FindAGrave and FamilySearch |

There are other explanations than FindAGrave’s usefulness for genealogy that explain its popularity. In fact, it was founded for a somewhat different purpose – to help people find the graves of famous people. I suppose the same group of people that always read the obituary section of the newspaper first might also find this kind of site interesting. That said, however, it is immensely useful for genealogists and I’m going to explain a bit about how it works and how it can work for you.

Finding Graves

FindAGrave has information on over 57 million graves in over 300,000 cemeteries in over 170 countries. You start by just going to their search page and trying to search for a specific person, or just by surname, etc. Keep in mind that in most cases, the graves that are added to the database are added manually by real people. That means if no one added the person you’re looking for, then they won’t be there. There are exceptions to this, as some databases of graves have been added, in particular lists of military graves. If you don’t know which cemetery your relative is buried in, and are using FindAGrave to help you locate the grave, try to add as much information as you can to the search – for example, if you know that your relative died in a specific state in the US, then add the Country (US) and State to the search, to make the search more focused.

Adding Graves

What if you search for the grave of a particular relative and you don’t find him or her? You can add them. To add a grave, you need to join the site (this is free), add biographical information on the person, and then add them to a cemetery. If (and this is rare) the cemetery is not on FindAGrave, then of course you can also add the cemetery first. The site actually has a few options for adding graves, including using an Excel spreadsheet to upload large numbers of graves in one cemetery at once.

Why, you might be asking, should you add graves to FindAGrave?

Well, first there is obvious purpose for many of creating a permanent memorial online for the person. Once you add a grave to the site, people can add content to the grave’s web page, like leaving virtual flowers and leaving notes in memory of the person.

If you know the location of the grave, and other relatives do not, then you are also helping your relatives to locate the grave. When a distant relative searches the next time on the site, they will now find the grave of the person you added.

It might seem odd, but these graves can also bring distant living family members together. If you list the grave of your great-grandparents, there may be many many cousins who also descend from the same people, and will find the memorial you placed online. This offers a way to connect with such cousins.

So let’s say you know which cemetery your relative is buried in, but not the specific location within that cemetery? You’ll want as specific a location for the grave when adding it to the site, meaning you should try to find out the specific section name/number, row number, plot number, etc. for each grave you add to the site. The quickest way to find out such information may be to simply call up the cemetery and ask. Most currently used cemeteries will have an office and will have the ability to look up the locations of graves. You should have as much information about each person you want to have looked up as possible – including names of spouses, maiden names, date of birth, date of death/burial, etc. as you never know how the grave information is indexed in the office. Also, if the name you are looking up is fairly common, or similar to other names, you will need the additional information to help the office worker to differentiate between different records.

Lessons Learned

When I heard about the recent toppling of graves by New York City sanitation workers when they were cleaning up the first big snowstorm last month I noticed that the cemetery sounded familiar. I checked my records and indeed my great-great-grandparents were buried in that cemetery. A further search on the cemetery showed that even worse, in the month prior over 200 graves had been vandalized in the same cemetery. I immediately called the cemetery, to find out the status of the graves. I didn’t know the specific location of the graves, but the person who answered the phone was able to locate them fairly quickly. It turned out, thankfully, that they were buried in a section of the cemetery that was unaffected by either the sanitation workers or the vandalism the prior month. This incident illustrated a few important points to me. First, that even though I have a record in my family tree file where some of my relatives are buried, I don’t actually have the exact plot location for most of them. Second, that cemeteries do not stay static, and unfortunately vandalism and other negative actions do occur in them that can mean the damaging or even complete destruction of one’s ancestor’s gravestone. Lastly, that although I do know the locations of some graves, I don’t know what is written on many of them.

I’ve mentioned in the past that information is only as good as the source, and that while information on a grave is probably accurate in terms of the death date, everything else would probably need to be confirmed elsewhere. Besides the dates of birth and death which are common on most graves, one piece of information that is common on Jewish graves is the name of the father of the deceased. Sometimes this is only written in Hebrew, while the English inscription if it exists only lists the name and dates. Sometimes a Jewish grave, especially of a person that was born in a foreign country, will list the town where the person came from as well. From a genealogists point-of-view, all of this information is very important (although it must also be confirmed with other sources).

Interestingly enough my great-great-grandfather’s grave in the Netherlands lists him as being ‘from Reisha’ which is not exactly true. Reisha (which is the Yiddish name of the town) is the current Polish town of Rzeszow. It was a major Jewish center for the region of Galicia in the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. My great-great-grandfather did indeed live in Rzeszow and had a couple of kids there (on either side of the rest of his children which were born in NYC). If you would thus assume that being ‘from’ Rzeszow meant he was born there, you would be wrong. He was born in the nearby town of Kanczuga and only moved to Rzeszow later. Why was he listed as being from Reisha on his gravestone? Perhaps there was more respect for those from Reisha? Maybe his children and grandchildren who buried him didn’t know which town he was from originally? I don’t know the answer to that, but in any event if you were to find the grave and assume the town listed was his birth town, you would be mistaken.

Finding Grave Information Online

Sometimes the best way to find information on graves is to look online. Some cemeteries or towns that administer cemeteries have posted information from their records online. Each cemetery obviously has different policies. Some cemeteries, especially famous ones, have had their graves indexed by volunteers and put online without coordination with the cemetery itself (in some cases the cemeteries no longer have active management). Even before calling a cemetery office, I would try to see if the cemetery or the cemetery owner (which could be a town or a religious organization, for example) has a website and if they provide information on the graves in their cemetery online.

As an example, I have relatives buried in Augusta, GA. A search for ‘augusta georgia cemetery’ on Google shows me a list of cemeteries in Augusta (generated by Google Maps) and then the web site search results which include a Rootsweb site and then the second result which is ‘Augusta, GA – Official Website – Cemeteries‘. That sounds promising. Clicking on that link brings me to a web site managed by the city of Augusta, and includes a list of the cemeteries in Augusta as well as a link to their ‘Graveside Database‘. It turns out that Augusta has put information on every grave in their cemeteries online in a database. Now, obviously, you will not always be so lucky as to find such as resource, but my point here is that you might find something similar and it’s definitely a great resource to have, especially since you can’t expect an office worker on a phone to answer unlimited questions about graves in their cemetery, but you can do as many searches on a web site as you want.

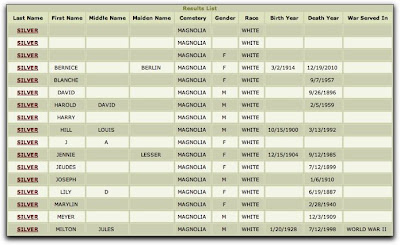

Let’s continue with the example. If I search for the name ‘Silver‘ in the database I get a list of 28 graves, all of which are in the Magnolia Cemetery. Looking at the list of graves indeed there are many of my relatives listed. An excerpt is below:

|

| Excerpt of search results from the Augusta, GA cemetery database |

So first of all, I now know which cemetery my relatives are buried in. I could have also found this information from other relatives, but now I don’t need to ask. Clicking on an individual grave gives me information on the grave. In some cases it is very basic, just what is on the grave itself. It usually lists the name of the funeral home, which if I didn’t know much about the person might be an additional avenue to pursue. The detailed page also lists the location of the grave, but in this case the locations are relative, not specific – i.e. ‘Buried in the new Jewish section at 15th St.’. That could be a problem if the cemetery is very large.

Some of the listings even show which company the person worked for, list family information (including married names of children and where they lived), as well as other biographical information. Now you might be asking yourself if you find such as site, why bother to add the graves to FindAGrave? First, not everyone looking for these grave many come across this web site. It’s possible the information on the web site will be removed at some point, etc. Those are all good reasons to add the information you’ve found on the web site to FindAGrave, but indeed there are two features of FindAGrave that give even better reasons – photo requests and virtual cemeteries.

Request a Photo

Once you find a grave on FindAGrave, or add it yourself, there is an amazing feature of the site called Request a Photo. Basically, for any grave that is in the system, you can request that a volunteer go and photograph the grave for you. When you register on the site, you have the option of adding your zip code and volunteering to take pictures of graves for other people. When someone wants a photo, the system e-mails all the people who live within a certain distance from the cemetery, and volunteers can accept the request and then they go to the cemetery, take pictures, then upload the pictures to the memorial page for the grave you selected. If you have relatives that are buried far from you, this is an great feature. Of course, there are many factors that will determine whether or not the graves will be photographed – how many volunteers are available, how busy those volunteers are at the moment, what the weather is like outside when you send the request, etc. but in many cases you will find photos uploaded within days of your request.

Virtual Cemeteries

As you research your family, you will frequently run into cousins that are researching the same line as you. You might share common great-great-grandparents, for example, and are both trying to research back further. You may also want to fill in their section of the tree, if for example, each of you are descendant from a different child of the same great-great-grandparents, they can provide information on their branch, and you can provide information on your branch. One way to connect with these other branches is to set up what FindAGrave calls ‘Virtual Cemeteries’. Basically, you can great a cemetery that is based on whatever criteria you decide. This could be ‘Descendants of Joe and Jenny Smith’ for example, and then you could add all the graves of the descendants that you find on the site, no matter where in the world they are located. If you know of others you can add them to the site first, then add them to this virtual cemetery. You can then share this virtual cemetery, which is really just a list of graves that you determine, with other relatives that are researching the same family. They can then fill in other graves of people they know about.

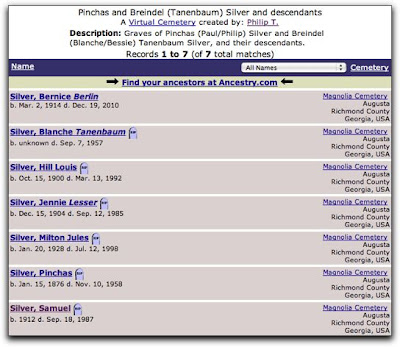

To continue my example from above where I searched for and found relatives with the surname Silver in the Magnolia Cemetery in Augusta, I added those graves to a virtual cemetery called ‘Pinchas and Breindel (Tanenbaum) Silver and descendants‘. This contains seven graves and looks like:

|

| A Virtual Cemetery on FindAGrave.com |

If you look closely, you’ll notice that everyone in this ‘virtual’ cemetery are actually in the Magnolia cemetery. That’s okay, it’s just the beginning. The goal from this point on would be to continue adding other descendants to the virtual cemetery as I find or add them. Other relatives can also help to add to this cemetery.

If you look closely you’ll also notice that six out of the seven listings have a list grave icon next o the name. That indicates that the grave has a photo associated with it. In fact, I requested photos of all seven, but one of the graves is not yet engraved because the person passed away too recently. The volunteer looked for the grave, then realized that it has no inscription yet, and instead of uploading a picture was able to indicate that it was impossible to take the picture right now.

Memorials

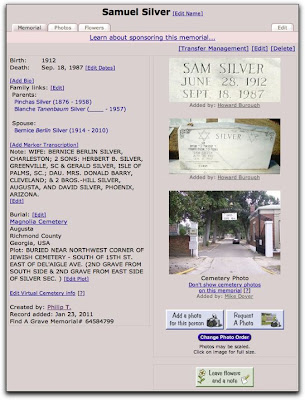

Just to give you an idea of what a memorial on the site looks like, here is one of the graves listed in the virtual cemetery:

|

| A memorial page on FindAGrave.com |

Looking at the page, you can see birth and death information. You can see other close relatives that are also on FindAGrave.com (his parents and his spouse). The same family information and grave location data from the Augusta site is listed, and there are three photos shown.

Note that the bottom photo is just of the entrance to the cemetery. If there is a photo of the cemetery, FindAGrave will show the photo of the cemetery. This is true even if there are no photos of the grave itself, so at least the cemetery photo will be shown.

The top two photos are photos that were uploaded by a volunteer who answer the Request for Photo. you can see the name of the volunteer who uploaded the photos as well.

So go check out FindAGrave.com, search for graves of your family, add those which you know about but are not on the site, and if you have the time volunteer to photograph graves as well. Adding grave to the database and photographing graves for others are both great ways to give back to the genealogy community at large.