For many Jewish genealogists, there is a kind of ultimate brick wall of reaching past the institution of surnames around two hundred years ago. Surnames were instituted in different areas at different times, but the Austro-Hungarian Empire, for example, instituted surnames by declaration of their emperor in 1787. When the empire expanded in 1795 absorbing part of Poland, it took in a large Jewish population which were for the first time required to take on surnames. Depending on where they lived, some Jews were not required to take on names for another decade or more after that, so if you have successfully tracked back your family to the point where they adopted surnames, it’s not so easy to reach past that point. There are some patronymic records, which are records that only list the first name of a person and the name of their father, that exist in these areas going further back, and it may be possible to track your family back for a generation before surnames, but that’s really the maximum most people will be able to accomplish if their families did not have surnames earlier (which some rabbinic families did, as did many Sephardim).

Adding to the difficulty of tracking back that far is that many Jews had little use for their assigned surnames in the 19th century. Thus, even though they had assigned surnames which the government used to assess taxes, conscript men into the army, etc., in terms of everyday usage Jews really didn’t care about their surnames. In addition, civil marriage was largely ignored by many Jews, as it generally was expensive. Jews tended to have religious marriages and only got civilly married if they or their children for some reason needed it. This thus lead to many civil marriages long after a couple had their children, something which might seem strange at first glance, but you need to realize thati n most cases these people did get married (religiously) before they had children, they were just not married from the perspective of the state.

So what happened if your parents did not have a civil marriage? In some cases it meant you would need to take your mother’s maiden name as your surname. That’s because even if your father was listed on your birth certificate, he was not legally married to your mother, and thus you needed to take on your mother’s last name for legal purposes. If you parents were legally married at a later date, a note could be written on your birth certificate in the town records showing that your parents were legally married, and thus declaring you as legitimate (and able to take your father’s name).

In the late 19th and early 20th century, civil marriage became easier for Jews, and thus around this time if you look at marriage records you will see a large number of marriages that seem to be relatively old people. In many cases these married couples already had children and grandchildren. As their children and grandchildren became more mobile and wanted to travel out of the small towns they had been in, they needed travel documents, and in some cases this was only made possible if their older parents got married (at least if they wanted to get travel documents with their father’s surname instead of their mothers).

I have a number of examples of children taking on their mother’s surnames in my own family.

In one case two sons took on their mother’s surname when born. One traveled through Europe and eventually ended up in the US, where the passenger manifest for the ship he arrived in the US on shows he and his children still with his mother’s surname. When he became a naturalized citizen a number of years later, however, he had already changed his surname to that of his father (as did his children). The second son moved to Israel, where he kept his mother’s surname. Thus two brothers living in different countries with different surnames.

Another case was utterly confusing for a long time, until I was finally able to put the pieces together. I had the birth record for a woman named Taube Traurig. I had birth records for children of Taube Traurig and a man named Wigdor Kessler. It seemed likely that the Taube Traurig from the original birth record and the Taube Traurig who had children with Wigdor Kessler were the same person. Then I ran into something strange, a death certificate for Taube Traurig (relatively young) before the children were born. This thus indicated either a mistake in the records, or a second Taube Traurig. The problem was that I didn’t have another Taube Traurig in my records that could be the mother (there was another Taube Traurig, but she was the mother of the two sons in the previous example – and a first cousin of the one in this example).

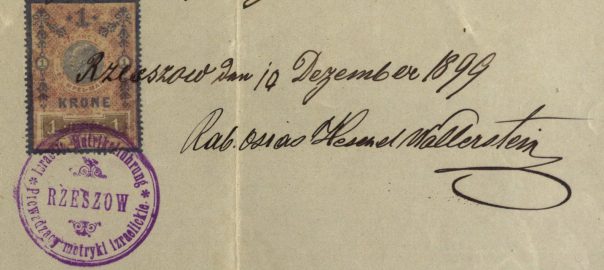

This was a mystery for a long time, until I noticed a notation on the original Taube Traurig’s birth record that had the name Wigdor Kessler on it. That made no sense to me. How could the name of her husband be on her birth record? Not being able to translate the Polish annotation, I posted an image of the birth record to ViewMate, a great service from JewishGen that lets you post an image or photograph and ask for help with translating records or any general problem-solving that you think others can help you with concerning the image. The responses I got indicated that the parents of Taube Traurig had been legally married in 1906, thus making all of their children ‘legitimate’ in the eyes of the state. Wigdor Kessler had signed the records of the couple’s children in 1906 as a witness that they were now considered legitimate by the state.

The person who translated the record for me had said something which stuck with me – he said Wigdor Kessler was not listed as the husband of Taube Traurig in the record. Now I didn’t necessarily think they would require him to state he was the husband, but I also guessed the person telling me this had seen other similar records and if he made the comment, he probably had seen others indicate they were the husband. I also found another record which showed Wigdor Kessler having a child several years later with a Taube Engelberg instead of Taube Traurig. That was utterly confusing since the original Taube Traurig had a sister Sara who had married someone with the last name Engelberg.

So what’s the answer here? The Taube married to Wigdor Kessler was the niece of the Taube in the original birth record. Searching through the marriage records I was able to find a marriage record between Wigdor Schopf and Taube Engelberg after all the children who were born where Taube’s name was listed as Taube Traurig, and before the child was born where she is listed as Taube Engelberg on the birth record. Who is Wigdor Schopf you’re asking? Schopf was Wigdor Kessler’s mother’s name (as shown in the marriage record). Traurig was Taube’s mother’s name. Her father’s name was Engelberg. Thus in all the earlier birth records she had been using her mother’s surname. Wigdor had used his father’s name all along on the birth records of his children, although why he had to use his mother’s surname in the marriage record is not clear.

Thus there were four birth records from 1898, 1900, 1902 and 1904 where Wigdor used his father’s surname and Taube used her mother’s surname. A wedding record in 1905 where Wigdor used his mother’s surname and Taube used her father’s surname. Finally, a birth record in 1910 where Wigdor uses his father’s surname and Taube uses her father’s surname.

What is not clear is why Wigdor was able to use his father’s surname in his childrens’ birth records but not his own marriage record, and why Taube used her mother’s surname in the first four birth records, but then used her father’s surname in her marriage record and in the later birth record. I would surmise that this later Taube’s parents were legally married in between the birth of Taube’s fourth child in 1904 and her marriage in 1905, although I have nothing to indicate that other than her own change of recorded name.

So what lessons have we learned here? If you’re researching your Jewish family in Poland or the surrounding countries, and they were born in the 19th century, don’t assume a person took on their father’s surname. Genealogy programs tend to automatically fill in the father’s surname when adding a child record, thus it’s easy to create a record where you assign the father’s surname even if you have no evidence that the child used the father’s surname. In many cases it might be a safe assumption, but in the case of 19th century Jewish records in Europe it clearly is not a safe assumption.

Two books that discuss some of the issues involved here are Suzan Wynne’s The Galizianers: The Jews of Galicia, 1772-1928 and Alexander Beider’s A Dictionary of Jewish Surnames from Galicia. If you’re asking why I’m pointing to two books that specifically deal with Galicia (a region of the former Austro-Hungarian Empire which currently is partly in Poland and partly in the Ukraine), it’s because the issues discussed here were particularly prevalent in Galicia, and as a big chunk of my family originates in Galicia, it’s also the area I know the most about (and of which I know about relevant books).

If you’ve had similar stories of relatives taking on their mother’s surname, please add your stories in the comments.