I think that there are three stages in the evolution of a genealogist.

The first stage is when they hear that family names were changed at Ellis Island they believe it.

The second stage is when they realize the whole Ellis Island Name Change thing is a myth, and basically no names were changed there.

The third stage is when they recognize that most myths are based on some aspect of truth, and even if you know a name in question wasn’t changed at Ellis Island, there is probably something to your family story that may help your research.

This leads into a different issue in that as genealogists we find a lot of the what, but a lot less of the why in our research. If we do discover that a family name was changed that is a what find, but it doesn’t usually tell us at all why the name was changed. This is one of many frustrations a genealogist comes across, as some changes don’t seem to make any sense at all. When you research your family and you find vital records, obituaries, etc. you get a lot of the what, but hardly any why.

I have a story in my family that tells the supposed why of a name change. My great-grandmother’s name was Rachel Cohen. She was born in what is now Belarus in 1898 and moved to New York sometime around the turn of the century. As an adult she looked for work but couldn’t find a job. Her friends told her her name was too Jewish sounding. So she changed her name and the next day got a job as a telephone operator at Macy’s. What did she change her name to? Ruth Cohen.

Why are Names Changed?

I was reminded of this story recently while reading a book from the National Genealogical Society called Petitions for Name Changes in New York City 1848-1899 (on Amazon) which was published in 1984 and lists the name change petitions on file in the Hall of Records in New York City for the years 1848-1899. The book is simply a listing of the 890 petitions made during that time period. As the full text of the petition is given, the interesting thing is that the reason for requesting a name change is also given as part of the request. Of course, a good portion of the name changes from this period deals with immigrants.

The reasons given for changing one’s name in this book generally fall into a few categories. There are people whose names put them up to ridicule, usually because the meaning of the name in the US is different than it was where the petitioner was born (Schitter to Schiller). There are those who wanted to simplify their names because it was hard to spell for English speakers (Lishniewsky to Lish, Klinkowstein to Kling, Koenigsberger to King, Sandelawsky to Sands). Some found that there were other people with the same name in New York (imagine that?) and wanted to change their name so there would be less confusion. Many name changes were children of divorced parents who wanted to take on their mother’s maiden name.

Frequently name changes followed other relatives who had done the same. Two petitions show a man who changed his name because the woman he wanted to marry objected to taking the name (Rindskopf), and the father who a year later changed his name to match his son (now Risdorf). Of course the second petition by the father doesn’t mention the reason the son changed his name, just that other family had changed their name to Risdorf. Perhaps someone whose German is better can explain the meaning of Rindskopf, but it seems to me to be meat head. Another Rindskopf, not clearly related, changed his name to Rieders.

At least two women actually took their deceased husbands’ names in order to help continue their businesses without difficulty. Many cases also show relatives offering the petitioner money to change their names, sometimes when the relative did not have someone to continue their surname and wanted the petitioner to change their name in order to keep the surname alive. Sometimes the receipt of an inheritance was dependent on the petitioner changing their name. What one finds in many cases is that the petitioner has already used a different name in business or school for many years, and now is trying to legalize the name they have been known by, in some cases, for decades.

One common reason, similar to my great-grandmother’s name change, was antisemitism or just general xenophobia. Many people changed their names to help get jobs, or improve their businesses, etc. Indeed, when you consider that the main reason most immigrants came to America during that period was for employment, it’s not surprising that people were willing to change their names to help get themselves a job. Sometimes the petitions state the reason clearly, that the person is Jewish and wants to change their name, while other times a euphemism is used such as “would be advantageous” or “will obtain pecuniary advantages.” Sometimes the person already had a job, but their boss didn’t want to bother calling them by a name he couldn’t pronounce and just called them something else. Over time the person would decide they wanted to use their new boss-chosen name legally.

One interesting name change, which might not seem so at first glance, was from Alter J. Saphirstein to Jacob Saphirstein. All the petition says is that he is known to his friends and in business as Jacob and now wants to take that name legally. What isn’t said is what Alter means. Alter means ‘old’ in Yiddish. You might wonder why a parent would name their child old? Well, it was actually quite common when the child in question was sick as a baby. If the baby had problems when born and the parents feared the child would die, they would name their child Alter to confuse the Angel of Death. Imagine the Angel of Death looking on his list of names for a baby to take, and finding someone named Old – obviously that can’t be the baby he was looking for, so move on. Well, that was the idea. In this case it would seem his name was Alter Jacob (notice the J. middle initial) and he was just dropping the Alter from his name, which he obviously never used himself.

My ‘Ellis Island Story’

So back to Ellis Island. Like many families, I had an ‘Ellis Island Story’ too. Technically speaking it wouldn’t have been at Ellis Island as my family arrived in the US before Ellis Island opened its doors in 1892, but it was of the genre. My grandfather told me that some of our family, whose name is Trauring, arrived in the US and when the clerk asked them for their name they didn’t understand and probably said a word in English they knew, Husband, and the clerk heard Hausman, and they ended up being known as Hausman. It sounds like a pretty standard immigration story.

Just to be clear, passengers arriving the US could not change their names at the port of arrival in the US. In fact, clerks at these ports worked off of passenger manifests provided by the shipping companies that had been filled out overseas. If a mistake was made to the name, it wasn’t done in the US port of arrival. There is no truth to the myth that people’s names were mangled by clerks who didn’t speak the same language as the immigrant, etc. as everything was written down and the clerks just copied the names from the passenger manifests. While my grandfather told me a story which is demonstrably not completely true, there were some pieces of the story which even my grandfather didn’t realize were true.

My gg-grandfather Isaac Trauring (my grandfather’s grandfather) married Ester Hausmann. They were the first generation of my family to arrive in the US. Knowing that my gg-grandmother’s maiden name was Hausmann added a bit of interest in the story I had heard about the immigration name change. Was there any truth to the story that someone whose name was Trauring had gone by the name Hausmann?

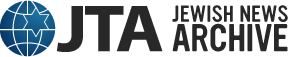

In later years I discovered an emergency passport application filed by Isaac Trauring in Vienna in 1914 that showed the name of the ship and the date he arrived in the US. Originally I got copies of this document through the US State Department, but later it turned up on Ancestry.com as well (with a page not provided by the State Department by the way). I looked up the passenger manifest for the ship mentioned in the passport application. Isaac wasn’t in the passenger manifest for that ship. The name of his wife, Ester Hausman, does show up in the manifest, however, as does the name of her brother Moses Hausmann and sister Chana Hausmann. In the manifest, however, it lists Moses Hausmann and Ester Hausmann as the same age and married to each other.

It occurred to me at the time that perhaps the Moses Hausmann in the manifest was actually Isaac Trauring, using identification documents from Esther’s brother to travel to the Unite States. The third person, Chana Hausmann, actually matches very closely in age to a real sister Chana, so perhaps the sister traveled with them. The one person missing, however, is Isaac and Ester’s daughter Katey which would have been two years old at the time. Was it actually Isaac on the ship as he said in the passport application? or did Isaac travel with daughter Katey on a different ship? or did Katey arrive with someone else at a later date? or maybe the ship listed was altogether wrong and the fact that there is an Ester Hausmann on this ship is just coincidence?

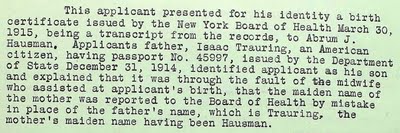

So fast forward a few more years and Ancestry.com released additional passport applications, including one by a child of Isaac and Ester that was born in 1897 in New York (the brother of my great-grandfather). In his application, there is an explanatory note that while his birth certificate lists his last name as Hausmann, his real last name is Trauring, and it was just a mistake made by the midwife who recorded the birth:

This wasn’t actually the first time I had thought to look up birth records under the name Hausman, but I hadn’t been successful in the past. However, here in front of me was proof that the name at birth of Isaac and Ester’s children (or at least this child) was Hausman. First, this would seem to give support to the theory that the Moses Hausmann in the passenger manifest was actually Isaac Trauring. Second, it offered real proof that a NY birth certificate existed for this child, if not others (they had at least three children in NY that survived to adulthood).

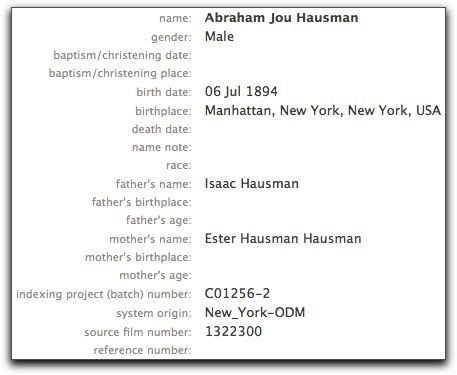

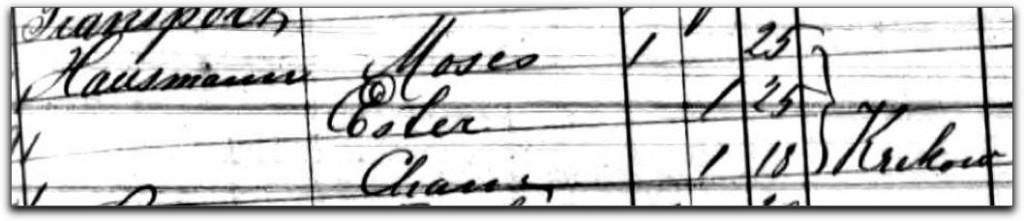

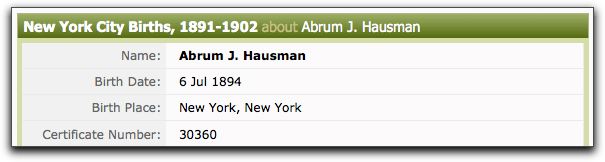

FamilySearch.org has New York births from this period indexed on their web site, so a quick search of their site (for Abrum J. Hausman born in 1894) returns an Abraham Jou Hausman, born in 1894, to Isaac Hausman and Esther Hausman Hausman. No that’s not a typo, it actually lists her last name twice, because it is her maiden name and her married name according to the birth certificate. We know why this is the case, since Isaac was using her surname, she had to list hers twice. The full FamilySearch.org results (click to enlarge):

Now, if one would want to order that birth record, you can do so from the NYC Department of Records, but I want to point something important about online indexes like that on FamilySearch. When ordering a birth certificate, it is helpful to know the certificate number (to insure the correct record is reproduced), something not listed in the FamilySearch information. Presumably FamilySearch had access to this information, but when they indexed the birth certificates they did not add in the field for certificate number.

If you were to do the same search on Ancestry.com, you would get the following result:

Note that while Ancestry.com has provided less information than FamilySearch.org, such as leaving out the names of the parents, it has provided the certificate number. Also note that the name is indexed differently in each database. In the FamilySearch.org record, it seems to be an expansion of what is actually on the certificate, where they guessed (or based on a list of abbreviations) that Ab was Abraham, but didn’t know what to do with the Jou (which is actually Joseph). In the case of Ancestry.com, they actually match the text as written in the passport application exactly, which leads me to believe that in both the case of Ancestry.com and the birth certificate shown for the passport application, there was probably an index created of these records that both Ancestry.com and the Board of Health clerk who issued the birth certificate transcription in 1915 used.

The moral of the story here is that if you have access to more than one database that covers the same information, it is usually worthwhile to search both, as they will not always give you the same information.

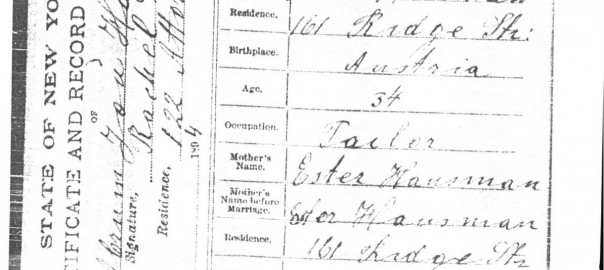

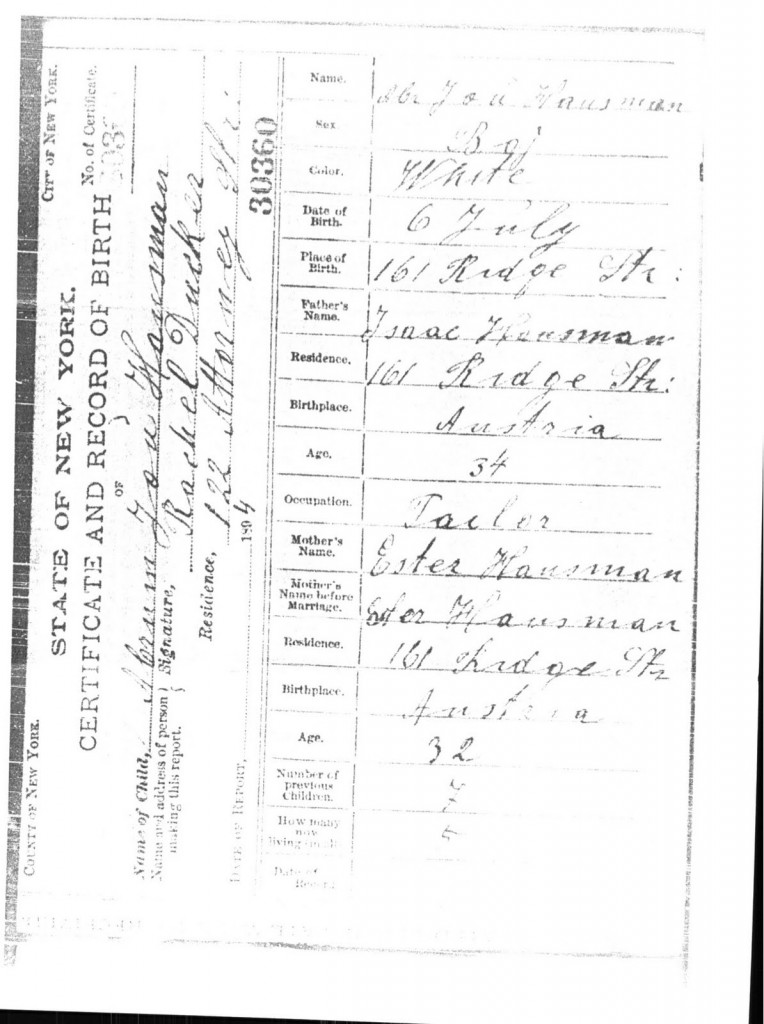

This is the actual birth certificate as provided by the NYC Department of Records (click to enlarge):

Now who here thinks it was a mistake by the midwife? Yeah, me neither. In fact, in birth certificates from two other births of children from this same couple, the Hausman name is shown in the same fashion.

If you look at the birth certificate closely, there is an important piece of information that you might miss at first glance. It shows the number of children born previously to the mother, and the number currently living. This is similar to the information in the 1900 and 1910 US Federal Census records (see my US Immigrant Census Form on the Forms page for more information about that). In this case it shows 7 children born, 5 still living. If one were unaware of the number of children in a family then this is a good way to check that you are searching for the correct number. Indeed out of the five listed as living at that point, I know of only three that survived into adulthood. I have an additional birth certificate of a child was born two years earlier, but whom I don’t know anything else about (so presumably died), and there is a child who died young before they moved to the US. It would seem that at least indirectly I can account for all the surviving children, although there is at least one death I am not aware of from any of my records. Of course, there is an alternative possibility, that the child born two years earlier did survive, and I just don’t know about her. That would mean that there were two deceased children I was unaware of instead of just one.

It would seem from the above that it was not likely a mistake, but rather the family was indeed living under the name Hausman. The name didn’t change at Castle Garden (where they would have arrived instead of Ellis Island which had not yet opened) and it wasn’t a mistake by some clerk, but rather for reasons not entirely clear, the family arrived using the name Hausman and kept it. Probably they just used ID documents with the Hausman name as they didn’t have any other IDs in the US. In later years, as evidenced by the passport application, all of the children were known by the Trauring name, not by the Hausman name, and indeed when Isaac Trauring later became a Naturalized citizen, there is no mention of using the Hausman name at all in his application. I believe this is because he left the US for a brief period after these births and returned with proper documentation before starting the Naturalization process.

So the story I heard years ago about a branch of the Trauring family going by the name Hausman was indeed true, and not only that, it was my own branch. Name change issues can be very complicated, as this episode shows, where the name changed and then changed back so that documents exist for earlier dates under the original name, then exist under the changed name, and later under the original name again. This is not so different from the issue of children using their mother’s maiden name due to lack of civil marriage by their parents (only having a religious marriage), then later switching back their father’s name, as described in my earlier article Religious marriages, civil marriages and surnames from mothers.

In the end, whether the reason for a relatives’ name change was because of pressure to fit in, overt racism, to get an inheritance, to take the name of one’s mother after one’s parents divorced, to reclaim a father’s name, to improve one’s business, or just because they had the wrong documentation when they arrived, the very real possibility that members of your family did change their names at some point, even if it wasn’t at Ellis Island, is something to consider when doing your research.