The origin of a major celebration was from the darkest time and the utmost of despair.

In Israel the Jewish holidays are celebrated slightly different than in other countries. The three pilgrimage holidays in which Jews would historically travel to Jerusalem to offer sacrifices at the temple – Pesach (Passover), Shavuot (Pentecost) and Sukkot (Tabernacles) – are celebrated for two days outside of Israel (for Pesach and Sukkot, two days at the beginning and two days at the end), and only one day within Israel. The reason for this is a historical inability to be sure that the lunar months on which the Jewish calendar are based was accurate outside of Israel. While in today’s modern world this is not a problem, the keeping of two days for each holiday outside of Israel (in the diaspora) has remained. In fact, many Jewish tourists who visit Israel during the holidays still keep the second day while in Israel. There are various reasons for this, but it’s worth pointing out the disparity of some Jews keeping a holiday where they cannot drive a car or take a bus, where they are generally dressed in their fanciest clothes, and the rest of the country going about its business as normal.

The end of the week of the Sukkot holiday is actually a pair of different holidays called Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah. In the diaspora these holidays take place on two sequential days at the end of the Sukkot holiday. On the eve of Simchat Torah, there is a celebration that includes dancing in a large circle holding Torahs and singing. This is called Hakafot.

In Israel, however, the two holidays of Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah are merged into a single day. This means that while Jews in other countries celebrate Hakafot on the second night, in Israel the holiday is already over.

This has led to one of the most interesting celebrations in Israel, that of Hakafot Shniyot (Second Hakafot). There is amazingly little written online about this celebration, so let me explain. The holiday is over so there are no restrictions on things like playing musical instruments or using a loudspeaker. In cities across Israel celebrations are held that have the traditional Hakafot dancing with Torahs, and take advantage of the fact that music and lights not available on the holiday can be used. These celebrations are attended by politicians and other dignitaries, but are open to everyone. The largest celebrations are in the major cities like Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, but celebrations occur in many cities and small towns. These are very popular celebrations which bring in many groups of people, from religious to secular, Ashkenazi to Sephardi, etc.

In looking up what was written online, I found various explanations for the holiday. One person wrote it originated with the Arizal, a 16th-century rabbi who lived in Safed as a way of showing solidarity with the Jewish communities in the diaspora. Others wrote it is an attempt to offer Hakafot to non-religious Jews, who would be more willing to come celebrate with real music in a public square than in the traditional Hakafot carried out in synagogues and without music. There may be some truth to these statements. The Arizal may have celebrated a second night of Hakafot (although I have no evidence of this), and the current celebrations may be a way to bring religious and non-religious Jews together, but neither of these explain where the modern celebration in Israel originated, nor why.

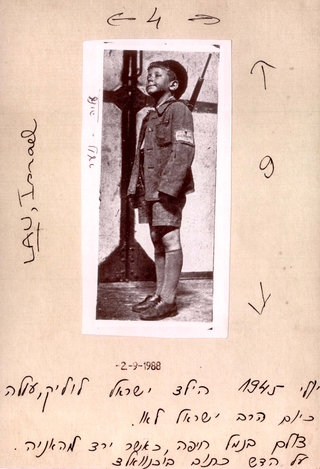

Which brings me to the main point of this article. I recently finished reading an amazing memoir by the former (1993-2003) Chief Rabbi of Israel, Rabbi Israel Meir Lau. The book is called Out of the Depths: The Story of a Child of Buchenwald Who Returned Home at Last and it is one of the most moving books I have ever read. I do not think it possible to read this book and not cry repeatedly. Rabbi Lau was only 2 years old when the second world war broke out. His parents were deported to death camps and murdered, and he was deported to two different concentration camps as a young child. Protected by his older brother who was enjoined by their father to protect the younger Lau and preserve the family’s 37-generation rabbinic dynasty, the young Lau ended up surviving Buchenwald, where he was liberated by American forces just short of his eighth birthday. Making their way to France with other young Buchenwald survivors (including a young Elie Wiesel who would remain in France), the two brothers insisted on going to the one place Jews could call their own, Eretz Yisrael (the Land of Israel). They received visas to then British-Mandate Palestine, and were among the first Holocaust survivors to arrive in what would become the State of Israel a few short years later (they were among the first because the British severely restricted Jewish immigration at that time – perhaps 150 Jewish children who survived Buchenwald were too hard even for the British to turn down).

One of the very interesting stories told by Lau, is that of his father-in-law Rabbi Yedidya Frenkel. During the war, Lau’s future-father-in-law was the rabbi of the Florentin neighborhood in Tel Aviv. After services ended concluding the Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah holiday in October 1942, Rabbi Frenkel asked his congregants to remain in the synagogue for a few minutes. I’ll quote from the book for the rest of the story:

The congregants wondered at his strange request, but they respected the rabbi’s wishes. He removed a Torah scroll from the ark, and in a voice quivering with emotion, announced to the congregation, “In Poland and elsewhere throughout war-torn Europe, the telephones aren’t working, the telegraph stations are closed, the mail no longer runs. Entire communities are cut off, and we do not know what has happened to their Jews. At this exact hour, in Warsaw, Kraków, and every other city in Poland, they should be beginning their Simchat Torah celebrations. But we do not know whether they are performing the traditional processions [Hakafot] holding the Torah scrolls. We are completely cut off from them, and despite our attempts to make contact, the communities do not answer. But all Jews are responsible for one another. Let us act in their stead and perform processions on their behalf, at least symbolically.”

Thus started the tradition of Hakafot Shniyot celebrations in Israel, from a place of darkness and despair. Rabbi Lau relates that in the years following the foundation of the State of Israel, as long as his father-in-law was alive, the Hafakot Shniyot celebration in the Florentin neighborhood were visited by the current Prime Minister and IDF Chief of Staff (as well as many other dignitaries). The celebrations spread, first to cities like Jerusalem and to the main square in Tel Aviv, to towns like Kfar Chabad, to army bases, and eventually across the entire country.

As we begin the commemoration of Yom HaShoa tonight here in Israel, it is worth remembering that one of Israel’s most popular and happiest celebrations, came from a time when Jews across the globe did not know the fate of their family members in Europe. When his future-father-in-law was starting this tradition, the young Lau was likely hiding in an attic with his soon-to-be murdered mother, being fed cookies to keep him quiet in case Gestapo soldiers might hear him when searching the building. It’s hard to conceive such events, not having experienced them, but we must remember, and I hope everyone will remember tonight that even out of despair can come celebration, and with the State of Israel hopefully no such event will ever be able to happen again.

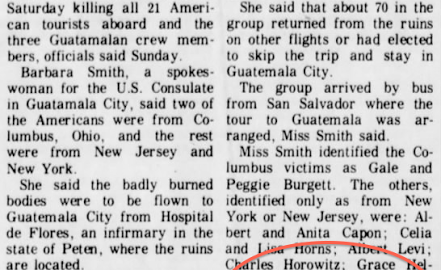

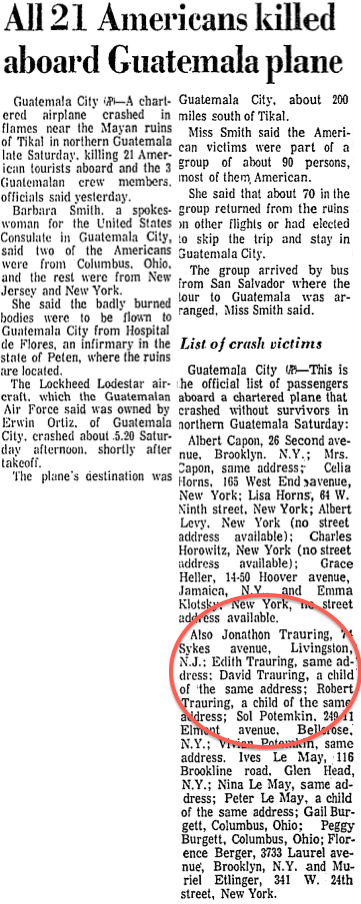

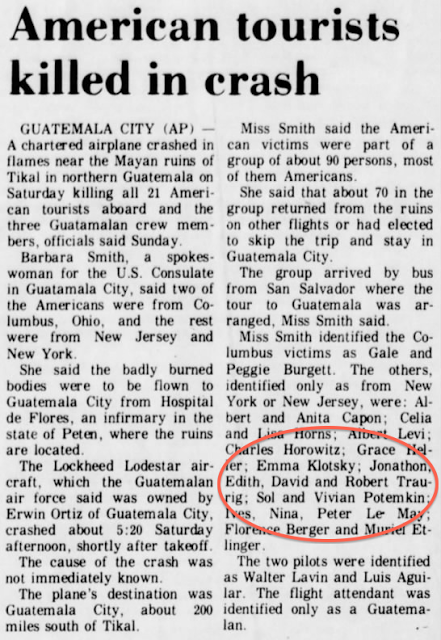

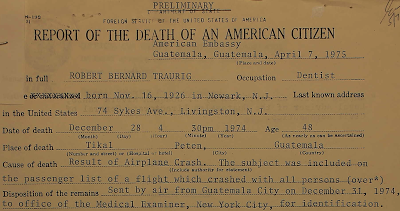

Some celebrations of Hakafot Shniyot from this past year:

Tel Aviv:

Kfar Chabad:

Ponevitch Yeshiva: