This is the story of seven women, all relatives of mine, who survived the German invasion of Belgium together through a crazy trip starting in Antwerp, passing through France, Morocco, Portugal, and ending in New York. I’ve written in the past about my grandfather (When my grandfather traveled to Nazi Germany to save his family) and his time before making it the US during WWII. I’ve always wanted to write about my grandmother’s journey, but lacked the documentation to visually tell the story. I now think I have enough to tell the story properly (if not completely).

My grandparents and their families knew each other in Poland, and then in Belgium, but my grandparents didn’t marry until 1943, when both had made it to New York. While their families followed similar paths for many years, at least one portion of their stories took a very different turn.

My grandmother was born Lipka Kleinhaus in 1922 in Rzeszów, Poland. She was the youngest of six children, her oldest sister nineteen years her senior. Her closest sibling in age, her brother Nusen, was ten years older than her. Like my grandfather’s family, her family found their way to Antwerp, Belgium in the 1920s. Once there, they entered the diamond business following a relative who had arrived earlier.

Some documentation of the family’s stay in Belgium can be found in the files of the Belgian Police des Étrangers which I’ve lectured on in the past. If you had family that lived in Belgium, see my Belgium page on where records can be found. The photo below, for example, came from one of the Police des Étrangers files.

In May 1940, when Germany invaded Belgium, my grandmother had only recently turned eighteen. Her older siblings were all married, and other than one brother who had gone to Brazil the previous year, all lived in Antwerp. When the Germans invaded, the family fled to the coastal town of Ostende, where they rented a house and hoped the distance from the front would keep them safe. When Belgium was on the verge of surrendering just weeks later, the family packed into two small Skoda cars and made the journey over the border into France. Thirteen family members crammed into the two tiny cars, fleeing Belgium with bombs still falling.

Unable to fit everyone in the cars, my grandmother’s two older sisters left their husbands behind in Belgium (both managed to survive and make it to the US via Cuba). The family drove first to Dieppe, France, not too far along the coast. It’s interesting when looking up events to see them in their context. Right between Ostende and Dieppe lies Dunkirk. The famous evacuation of allied troops from Dunkirk, portrayed a few years ago in a movie by Christopher Nolan, was taking place at the very same time that my family was fleeing Belgium (and for the same reason). From Dieppe they went to nearby Rouen, perhaps a better place to hide.

At some point one of the cars was disabled. It was believed that someone stole a part from the car. The family went from barely fitting in two cars, to now needing to split up. Believing the men to be at the most immediate risk, my great-grandfather, two of his sons and their wives, and one young grandson, took the sole working car and drove towards Bordeaux. The remaining seven women, my grandmother Lipka, her mother Feiga, her two sisters Sabina and Czyze, and three nieces, followed in taxis and however they could, to meet the car in Bordeaux.

These are the seven women:

| Name | age |

|---|---|

| Feiga Kleinhaus | 59 |

| Sabina (Kleinhaus) Plutzer | 37 |

| Anna Plutzer | 13 |

| Dora Plutzer | 8 |

| Czyze (Kleinhaus) Silber | 35 |

| Sara Debora Silber | 10 |

| Lipka Kleinhaus | 18 |

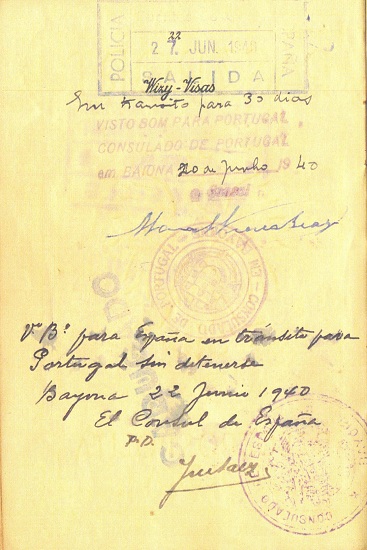

Upon arriving in Bordeaux, however, the seven women found out that their family in the car had left and gone to Bayonne further down the coast. Arriving in Bayonne, they then found the car had already crossed the Spanish border. The six family members in the car had lucked upon the Portuguese Vice-Consul Manuel Vieira Braga, and received visas for Portugal which allowed them to cross the border into Spain. Thousands of visas were handed out over a few days by Braga and his boss Consul Aristides de Sousa Mendes (see the Sousa Mendes Foundation for more information about Sousa Mendes and the people he saved).

Perhaps knowing that the visas were issued illegally and might not hold up very long, they chose to cross the border by car as soon as possible. Perhaps also related was that just two days after receiving their visas, France surrendered to Germany. At that point they probably couldn’t wait any longer. The car managed to get to Portugal, where the six family members lived for the better part of a year while waiting for visas to the US.

The seven women, however, were too late to receive visas to Portugal. Now in Bayonne, they tried to find a ship willing to take them away from France, without having visas. As the story was told, they tried to get onto a ship heading for England, but were prevented by Polish soldiers who, also fleeing the Germans, had blocked Jewish refugees from getting on the ship. As the ship pulled out into the Atlantic, German airplanes bombed and sank it.

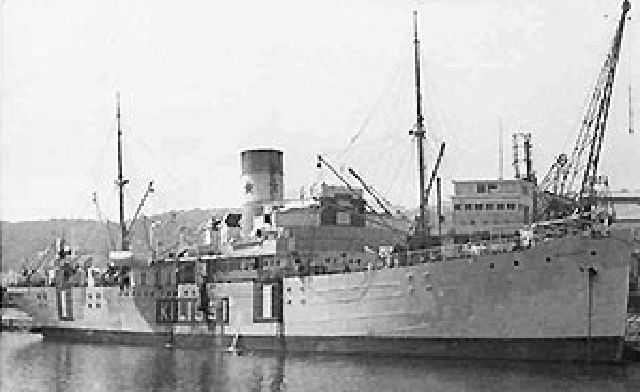

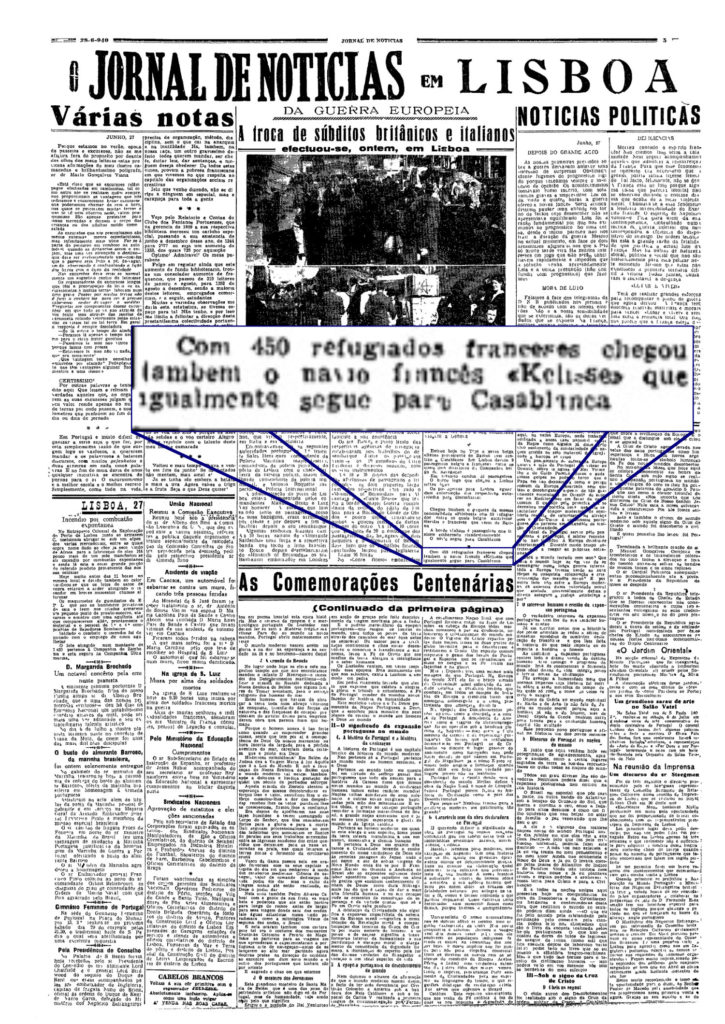

Thousands of refugees filled the docks looking for ships to take them, but none would. Finally, one captain (Rene Jean Moro) said yes. In charge of a banana transport called the Kilissi, he got his crew to agree, and then let on hundreds of visa-less refugees. Until recently I didn’t know the name of the ship, nor of the captain, which saved my family’s lives (more on how I found those in a moment). A few mentions of the Kilissi can be found online, including a brief history posted in a marine forum. That history mentions the journey from Bayonne to Lisbon that ended on June 27, 1940, as well as the rest of its history up until it was sunk by the British in 1944.

In a serendipitous twist, while reading a Facebook post shared by Randy Schoenberg, I started reading a description that sounded very familiar. Randy was one of the subjects of the book The Lady in Gold, about Gustav Klimt’s famous painting Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I. Randy had helped recover the painting from the Austrian government, after it had been looted by the Nazis and ended up in a Vienna museum. While that aspect of the story was covered in the movie Woman in Gold (starring Ryan Reynolds as Randy), there were other parts of the book covering different parts of the family connected to the painting. One of the those parts describes the very same struggle to find a ship in Bayonne, and the captain allowing them on the ship. The book’s author, Ann-Marie O’Connor, had written about the journey of Emile Zuckerlandl and his mother, and how they ended up on the Kilissi. The specific excerpt of this story from the book is reproduced in a blog post published in 2016. The post that Randy had shared was a post by O’Connor explaining that she had finally identified the captain of the Kilissi as Rene Jean Moro. In the book (published nine years earlier) she had known the name of the ship, but not the captain. O’Connor had discovered the name of the captain in a series of documents, including documents from the French resistance, which Moro later joined. Now because a cousin of Adele Bloch-Bauer happened to travel on the same ship as my family, I was able to discover the names of the ship and the captain.

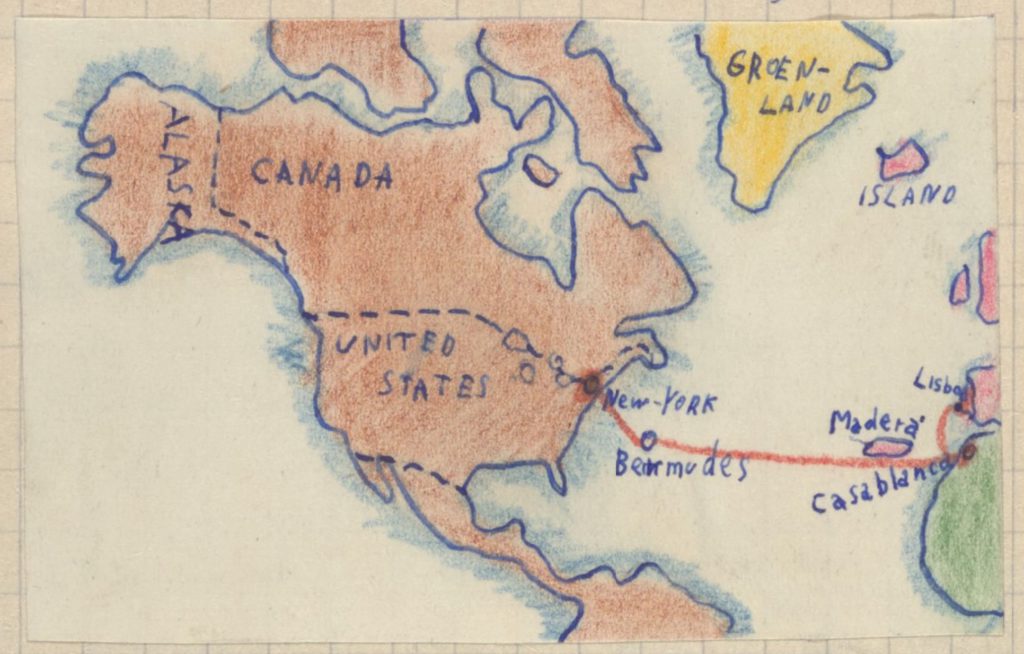

The ship left France and headed for Lisbon, Portugal. Read the quite dramatic description of the journey in The Lady in Gold (excerpt linked to above). After arriving, the Portuguese government wouldn’t let any of the refugees disembark. The refugees didn’t have visas, and therefore could not step foot on shore. It’s strange to think that the two halves of my family that had been separated maybe a week earlier two countries away, now could have been in the same city, but wouldn’t see each other for more than a year.

Instead of disembarking in Lisbon, the refugees were moved to a French navy vessel, and taken to Casablanca. The account of this refugee ship was told in The Lady in Gold, and also in the story Desperate Voyage by Terry Wolf in Arnold Geier’s book Heroes of the Holocaust. Geier’s version has an amusing illustration showing the crew tossing bananas over the side of the ship to make room for the refugees. The two versions map very closely, including the fact that when the refugees were led off the Killisi onto the French navy ship, the crew stood at salute, and the refugees sang the Marseillaise, the French national anthem, in honor of the crew.

My grandmother’s niece, who was 13 at the time, recounted in an interview when she was older that she and some of the other kids were able to run around the Navy ship, and even managed to get food from the ship’s kitchen. They had been stuck on the Kilissi and even when they arrived in Lisbon, the Portuguese would not provide any food to the refugees. They had a supply of bananas, but as you might imagine, eating only bananas was not very good for one’s stomach. This niece’s sister, slightly younger at 8, never ate bananas again. She was probably not the only one from that trip to avoid them.

In Casablanca my grandmother, and her mother, sisters and nieces, were initially placed in an internment camp, before being taken out by HIAS. Those refugees able to pay their own way were able to leave the camp, and be placed in apartments temporarily. They spent a night on mattresses on the floor of the HIAS office, and then rented an apartment in Casablanca where they lived for several months.

Casablanca was at the time the center of a massive influx of refugees. In addition to those refugees arriving from France on hundreds of ships, were 13,000 civilian refugees from Gibraltar, who had been sent there in May in anticipation of conflict. Around the same time as my family arrived, the British navy sunk several French ships off the coast of Algeria, killing nearly a thousand French sailors. That event caused the 13,000 Gibraltar civilians to be summarily kicked out of Morocco. It was in this mess of conflict and refugees that my family arrived in North Africa.

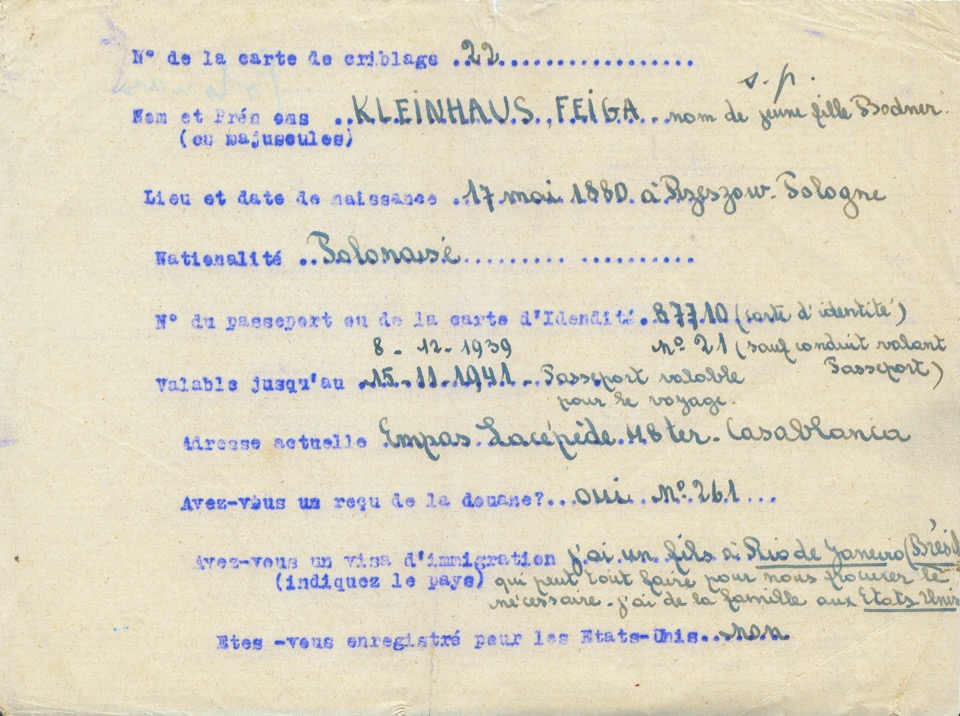

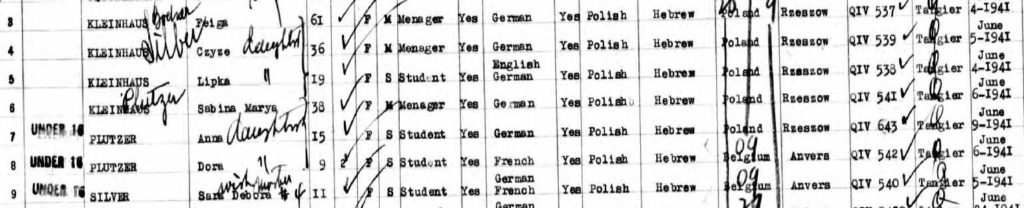

Among those who assisted them was Hélène Cazès-Benatar, the first female lawyer in Morocco. In 1940 Cazès-Benatar set up the Morocco Refugee Aid Committee, which was supported by the American Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) to aid refugees fleeing Europe. The Central Archive of the History of the Jewish People (CAHJP) in Jerusalem contains some of Cazès-Benatar’s papers from this period, including some registration cards of refugees, lists of train transports to other cities, etc. Among those are four cards for my family – one for my great-grandmother Feiga, one for my grandmother Lipka, one for my great-aunt Sabina and her daughters Anna and Dora, and one for my great-aunt Czyze and her daughter Sara.

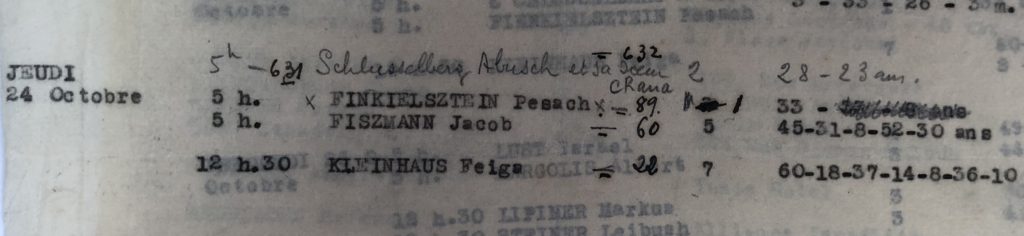

My family spent about four months in Casablanca, before they were forced, probably due to lack of space in Casablanca, to move to Mogador. Cazès-Benatar’s records again show the family on a list of those taking trains to Mogador. Under the name of my great-grandmother, the ages of all seven women are listed on the right. At 12:30pm on October 24, 1940, the women made their way by train to Mogador (currently called Essaouira), further down the coast from the more central Casablanca.

Perhaps not a coincidence, the first anti-Jewish laws (modeled on the German Nuremberg laws) had been passed in Vichy France just weeks earlier on October 3, 1940. Moving to Mogador might have been an attempt to stay a step ahead of the anti-Jewish laws, which might have been more easily implemented in a large central city like Casablanca.

Here the documentation in Morocco more or less ends. From what I know, the women did not spend more than a few months in Mogador. Instead my grandmother worked very hard to get papers to go to Tangier. Before the war Tangier had the status of an international city. In June 1940 Spain had occupied the city, which was surrounded in any case by Spanish-controlled areas of Morocco. Spain was nominatively neutral during the war, although it did make some deals with Germany. Tangier had another advantage besides being more neutral – it had flights to Lisbon. Almost all ships leaving for the United States at the time were leaving from Lisbon, and the rest of their family was also in Portugal. From that perspective, getting that much closer to them makes sense.

According to the passenger manifest from when they arrived in the United States, the women all received visas in Tangier in early June 1941. Some time after that they were able to get to Lisbon (probably by airplane), and then boarded the SS Nyassa in Lisbon on July 24, 1941. The Nyassa ironically made a stop in Casablanca to pick up more refugees, stopped in Bermuda on the way, and ended up arriving in New York on August 9.

Interestingly, a there is a journal kept by a young German Jewish refugee that ends with the same journey on the Nyassa. See the journal of 14-year old Hans Vogel on the USHMM web site. The part with the Nyassa starts on page 37 (pg 62 in the journal itself) and goes until the end.

The arrival of the Nyassa made the news in New York, when the ship’s mast struck the bottom of the Brooklyn Bridge:

There is still a lot more to this story yet to be discovered. Other than the small newspaper mention of the Kilissi arriving in Lisbon with 450 refugees, I’ve found no other contemporaneous account of the fact that the ship made the journey with refugees. I don’t know the name of the French navy vessel which took the refugees to Casablanca. Do French navy archives have information on this journey from Lisbon to Casablanca? Is there a list somewhere in a French or Moroccan archive showing which refugees were transferred? Does HIAS have records of who they removed from the internment camp? The internment camp was likely one set up in a military camp in Aïn Chock on the outskirts of Casablanca. Are there records of Aïn Chock that list the internees?

What about the visa process for my family, both those in Portugal and those in Morocco. The ones who made it to Portugal by car made it to the US in in a series of ships leaving Lisbon between February and April 1941. The women received their visas in June, and left by ship in July. Are there files on the visa process somewhere? Perhaps the records of HICEM or JDC have documents on their efforts to get visas. Initial checks of the HICEM records in NY have not turned up files on my family. Maybe there are records in Portugal, France or Morocco.

Other questions also remain. In one recorded interview with my grandmother’s niece, she describes the above, including the fact that a well-known author was there that wrote about them. I had long heard about these womens’ story being written somewhere, but never found a copy or even knew who wrote it. After a cousin pointed out the interview, and that she mentions the name of an author that wrote about them, I discovered it was the Yiddish author Moshe Dluznowsky. Dluznowsky’s most famous play, the Lonesome Ship, seems it could be based on the very same voyage of the Kilissi (although very much dramatized).

When that play was put on in Los Angeles in 1958, one of the minor roles was played by Leonard Nimoy. He was already a TV actor, but not yet famous. That play, however, is fictional. Is there a story somewhere written by Dluznowsky specifically about these seven women? It’s hard to determine since he wrote in many different newspapers, and mostly in Yiddish. One cousin claimed the story written about them was actually called The Seven Men, in what I can only assume was a dated tribute to them surviving as well as men would have in the same situation. Does that story exist somewhere?

I’ve long wanted to write about this story of survival. Some serendipitous events led to me learning more about it, and encouraged me to do additional research. This was helped by the fact I created a Facebook group for descendants of a common ancestor couple, where discussion of some aspects of this journey took place. It was also helped by my friendship with Randy Schoenberg, who shared Anne-Marie O’Connor’s post at the right time. I hope this article encourages others to look into their family stories more, and find documentation that illustrates the stories one may have only heard told by relatives. I do believe that in genealogy (and most things), you make your own luck. One could describe the coincidences above as serendipitous, or lucky, or fortuitous, but those things happened because I fostered those relationships, and because I set up that Facebook group. So go make your own luck, and start sharing what you know with your relatives.

If you know anything more about the journey of the Kilissi, or any other aspect of the above story, please share your knowledge in the comments below.

Thank you for this amazing story and your thoughts on purposefully sharing.

Wow. This is fascinating. Anna zl was my grandmother and I first heard parts of this story from her when I was 12 and wrote a paper for school on family history. It’s amazing you were able to map it all out with dates and documents. Thank you!

Absolutely. Anna Plutzer Beer was my mother and I grew up hearing much of this story. It’s amazing seeing it documented like this Philip. I’m also grateful to my son Dovie Maisel (Aurital’s brother) who had the presence of mind to sit and record my mother recounting her journey on one of his visits to her, enabling a detailed first hand account of where they went and what took place on the way.

Hello Philip, thanks for putting the story together. I’m sure it took a long time and a great deal of perseverance to piece together the essence of the saga of our family during WWII. Just a few comments or additions. The Germans attacker’s on Friday May 10th 1940. For the first and only time ( to my knowledge ) the Antwerp diamond bourse opened its doors on Saturday to allow its members to go to the vaults in the basement and remove their valuables. That is what my father , Wolf, and Albert’s father, Jehuda ( or Idel ) did. This allowed them to finance your grandma’s and our escape from Belgium. Our little trip through northern France and Spain to Portugal was not without a little excitement. We were bombed on the road several times and escaped a German paratroop ambush. The automobiles we had were two Skoda convertibles, one red the other green, each a small four seater. The two men shuttled back and forth to convey the family ( 15 in Toto ) just ahead of the Nazis. The refugee cars were forced to park in restricted fields for the night in most places and one morning one of the two cars was missing a carbeurator. That’s when we were forced to split up. My grandfather Chaim, Idel,Poria, my parents and I continued by car to Portugal where we stayed for eight plus months until we could get visas and passage to the States. My mother and I arrived first on February 17, 1941, Chaim about three weeks later, my father on MRch 31, 1941 , and Idel and Poria about six weeks later. I arrived on the uss excambion, my Dad on the Serpa Pinta. Once again it was a great job you did gathering all the documents and piecing the story together. If I can ,I will answer any questions you might have. Oh yes, the reason we were able to get our visas to get to the USA was they we had a cousin Tona Rosenblum ( née Antoinette Kleinhaus ) who had come to the states in 1939, ostensibly to see the Worlds Fair. Jacques Roseblum, Tona, Solange and Maurice were already in NewYork when we got here. I wouldn’t be surprised if a few $ were exchanged in the process as well. Anyhow, if I can add anything or answer any questions I will do my best. Thanks again, Sylvain

Sylvain, thank you for adding details. As the only living participant in the escape from Europe described in this article, I am grateful for any details you are able to add.

Thank you Philip for this recount of this brave and dangerous journey that allowed us all to be here today. My grandmother Sabina Plutzer and my mother Dora Plutzer are two of those seven women.

Thanks Philip for your important and thrilling story. I hope that you are still interested in pursuing the initiative concerning Captain Moro. If so please write. Your article is an important contribution to a claim to honor his memory

Hi Jean Pierre, my name is Emily Dawn Weaver my mom’s name is Mary Ellen Ridenour. I’ve been trying to find you your my great great uncle I am the granddaughter of Marguerite Bouvier McMillan Titchenelle your sister that escaped the french holocaust by immigrating to the usa . I live in the United States with my family in Pennsylvania. I have dreamed of being able to meet you and learn about our family over seas. I hope to hear back from you.

Who is Jean Pierre?