From sadness to happiness and wedding rings.

While my last article looked at changes from the surname Traurig to Trauring which were mistakes, this article looks at changes in the name Traurig that actually did happen – leading to Trauring, Vesely, Smutny, and Al Yagon.

This article is a fairly long look at how names, or more specifically one name, changed over the past two centuries, using a number of sources including JRI-Poland (covers Poland), Genteam.at (Austria), Yad Vashem (Israel), Historical Jewish Press, FHL Microfilms, old-fashioned gumshoeing, and a bit of luck. While not so many people reading this article may be interested in what accounts to a one-name study of sorts, I think the research methods and family situations discussed would be useful for anyone trying to track down members of their family whose surnames in past centuries might have changed.

The Original Name

About 150 years ago, my family’s surname was Traurig. Traurig in German means ‘sad’. My family lived in the small town of Kańczuga, in the Galicia region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire (the town is now in Poland). Only about 50 years earlier, most people in Galicia didn’t have surnames. Surnames were introduced in Galicia after its consolidation into the Austro-Hungarian Empire as a way to make it easier to tax citizens, and conscript them into the army.

Why Change?

When surnames became required, why would a family choose a name that meant sad? Family legend has it that indeed they didn’t choose the name at all, but rather were assigned it by an antisemitic local bureaucrat. The story goes on that this bureaucrat actually was something of a joker, and named two brothers differently – Lustig and Traurig, or in English – Happy and Sad. The chronicler of this family legend (a distant cousin) even mentioned some members of the Lustig family that were related to us, including the owner of the famous NY restaurant chain Longchamps – which I found out was founded by one Henry Lustig with funding from his brother-in-law Arnold Rothstein. Yes, that Arnold Rothstein. I’ve never been able to make a direct connection to the Lustig family, but interestingly enough I did find an Abraham Joseph Lustig in records that came from Kańczuga Abraham Joseph was actually a very popular name combination in my family from Kańczuga so that’s another connection. Maybe there’s something to that legend…

My Family’s Name Change

Our family changed their name within a generation or two to Trauring, which means ‘wedding ring’. I suspect it was simply to avoid the negative meaning of their original name. It’s not clear exactly when the name change occurred, but certainly by the 1880s my family was using the Trauring name. I suspect in fact that they used it much earlier, but only changed it officially once leaving Kanczuga and venturing out to other nearby towns. It is only in other towns that the name Trauring begins to show up, even while the Traurig name continued in Kańczuga until much later.

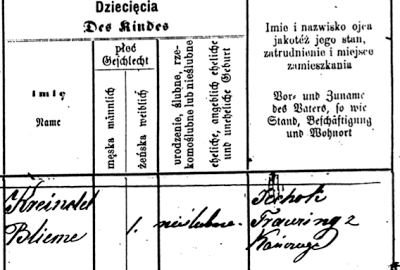

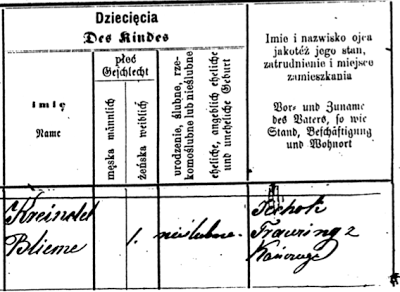

My original discovery of the name change came when I found my great-grandfather’s older sister’s birth record when searching on JRI-Poland. Kreindel Blime (later known as Katie) Trauring was born in 1882 in Rzeszów, a larger city not too far from Kańczuga. I didn’t then know the connection to Kańczuga and actually thought my family was originally from Rzeszów. When I ordered a copy of the birth record, however, it clearly showed that her father Isaac Trauring was born in Kańczuga. When I tracked down the birth records from Kańczuga (also through JRI-Poland) I was surprised to find there were no Traurings at all. There were, however, a lot of Traurigs. One Traurig was an Isaac Traurig born in 1862. So Isaac Traurig was born in 1862 in Kańczuga, and his first child was born 20 years later in Rzeszów with her father’s name listed as Isaac Trauring.

|

| Detail of Kreindel Blime Trauring’s birth record from 1882 |

Let me be clear that just finding a person with the same name about the same age in a town does not make them the person you are seeking. I later went on to find many other documents that backed up this record, showing the same town and the same birthday for Isaac Trauri(n)g.

I’ll save you from the details, but another branch of the family shows up in Lancut, also nearby, also went by the name Trauring, and can also be traced back to Kańczuga originally. This probably either indicates that the name change was much earlier than documented (since two separate branches changed their name) or that the two branches coordinated the name change even after they were split between different locations.

Are All Traurigs Related?

With our family name having been Traurig for only for a few decades, and being a fairly common word in German (and a much more common surname than Trauring), I always suspected that that while there are lots of Traurigs out there, none (or few) were related to my family. Indeed, many of the Traurigs I’ve come across have been Cohanim (Jewish priests who receive that status via patrilineal inheritance). Strictly speaking, since my family are not Cohanim (Hebrew plural of Cohen), it should be impossible to be related to Traurigs who are Cohanim (since it is inherited patrilineally).

I said strictly speaking, since it’s not actually true, as many people in Galicia received their surnames from their mothers – as I have discussed in two previous articles: Religious marriages, civil marriages and surnames from mothers and Name Changes at Ellis Island. Thus perhaps one branch received the Cohen status from their father, but their surname from their mother. That said I’ve never found a connection beyond the Traurigs that originated in Kańczuga.

Other Family’s Changes

Since it’s possible some Traurigs are related to my family, I continue occasionally to look into Traurig records, and see if I can find any connection. In doing so I’ve run into something interesting. While my family changed their name well over a hundred years ago, other Traurigs have also changed their names. Indeed I’ve run into at least three other Traurig families that have changed their names.

Ferdinand Traurig (I)

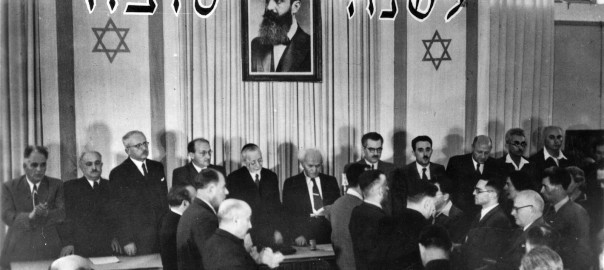

If you look at the list of people on Schindler’s Lists (I use the plural here because there were in fact more than one version of this famous list) you’ll find one Ferdinand Trauring. JewishGen gives some background on these lists, and has two versions of the list included in their Holocaust Database. One version of the list is one that was published in 1944 in Hebrew in the now-defunct newspaper Davar.

While I’ve only mentioned it in passing before, one very important resource for Jewish genealogy is the Historical Jewish Press web site. A joint project of Tel Aviv University and Israel’s National Library, it is slowly scanning many Jewish newspapers from around the globe and making them searchable online. Many of these newspapers are from Israel and are in Hebrew, but of the 35 newspapers currently scanned, the languages also include English, French, German, Hungarian, Judeo-Arabic and Yiddish, as well as papers from Algeria, Austria, France, Hungary, Prussia, Morocco and Russia. One of the papers available on the site happens to be Davar. Searching for טראורינג (Trauring in Hebrew) indeed finds the Davar-published copy of Schindler’s List with an entry for Ferdinand Trauring born in 1892:

|

| Schindler’s List Published Sep 3, 1944 in Davar |

You might be wondering why I’m talking about a Ferdinand Trauring and not Ferdinand Traurig. Well, Schindler’s List was my introduction to this man, but not the end of the story. I didn’t know how this Ferdinand Trauring was connected to my family, if at all.

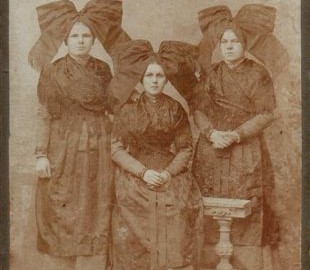

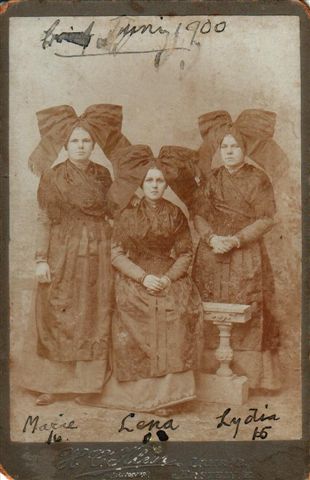

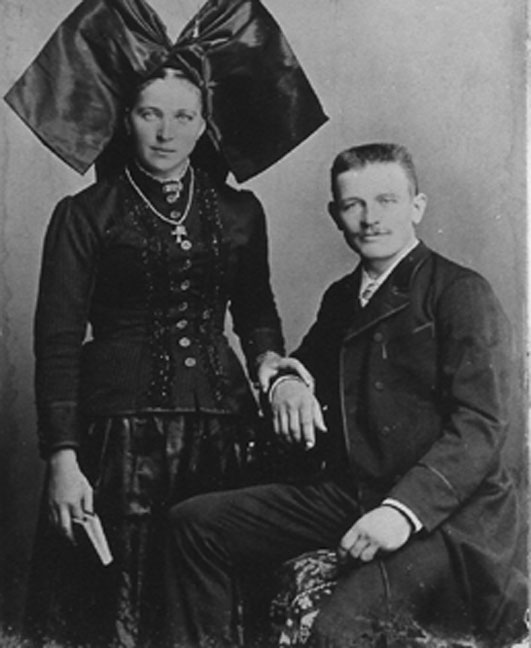

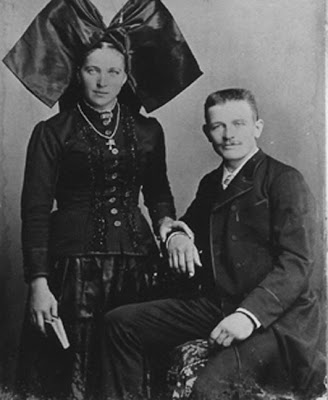

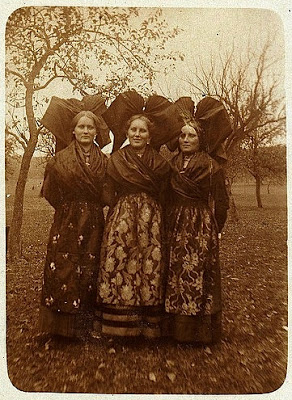

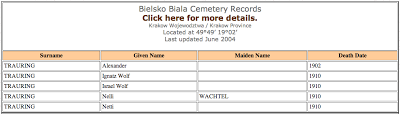

There were other Traurings I couldn’t find a connection to either, including a couple named Israel Wolf and Netti/Nelli (Wachtel) Trauring. I was introduced to this couple by accident. Another researcher who was looking into the Traurig family had received photographs from a researcher in Poland who had photographed graves of Traurigs in a certain cemetery. Except the photographs were not of Traurigs at all, but of Traurings. Since she didn’t think the photographs were relevant to her, and we had connected online to discuss possible connections, she had mailed me the photographs. I haven’t been able to locate the photos of the graves that were sent to me more than a decade ago, but the same graves are shown in records from JRI-Poland:

|

| Cemetery records of Ignatz/Israel and Netti/Nelli Trauring (JRI-Poland) |

In the cemetery records, there are two listings for Israel/Ignatz and Netti/Nelli using each variation of the first name. Nelli’s maiden name is given as Wachtel. Both died in 1910.

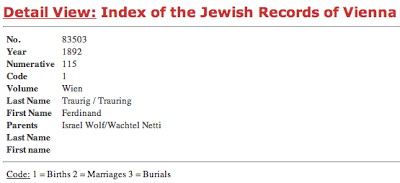

Later, while searching the site Genteam.at, an amazing resource for families that had relatives living in Austria, I found by chance the birth record of Ferdinand Trauring. Genteam.at, for those who don’t know about it, is a volunteer effort that has already indexed more than 7 million records from Austria, including many Jewish records. Here’s the record as listed in Genteam.at:

|

| Birth record for Ferdinand Trauring from Vienna in 1892 (Genteam.at) |

Two important things to notice in the record. First, his parents are the aforementioned Israel Wolf and Netti (Wachtel) Trauring. Second, Ferdinand’s last name is listed as both Traurig and Trauring. I’ve never seen a record before that listed two last names on a birth record, so this is interesting. Presumably, since we know that Israel Wolf and Netti, as well as their son Ferdinand, later went by the name Trauring, the use of both names indicates that the family name was previously Traurig.

Digging a little deeper, using the information from the Genteam.at index, I searched through the FHL Catalog of microfilms to see if they had made copies of birth records in Vienna from that period. I found a series of microfilms dealing with births, marriages and deaths from the Jewish community of Vienna called Matrikel, 1826-1943, and among those films is film 1175374, titled ‘Geburten 1890-1892’. Gerburten is German for Births, so that seems like the right film.

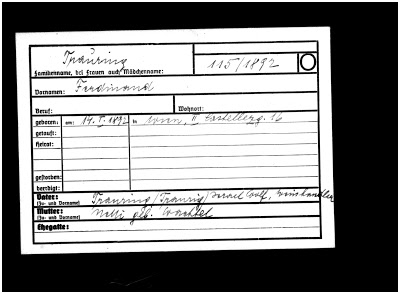

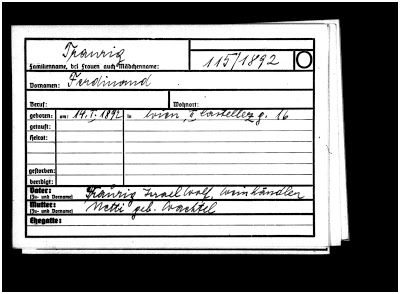

Using the information from the Genteam.at record, and the film umber I had found in the FHL catalog, I submitted a request on Genlighten.com, where you can request document retrieval from researchers who have access to various archives and libraries, including the FHL. A researcher, whom I can’t name not because I don’t want to, but because he’s no longer on Genlighten and it doesn’t show the names of previous service providers, looked up the original birth record of Ferdinand Traurig/Trauring for just $10. For that he retrieved not only the original birth record, but all the index cards that contained the surname Traurig or Trauring as well, which was on a different film (it’s good to hire someone familiar with the records you are trying to access). Here’s the index card that matches the record from Genteam.at above:

|

| Index card of the birth of Ferdinand Trauring from FHL microfilm |

You’ll note all the same information, although here the double-surname is listed for the father Israel Wolf, not for the surname on the birth record. That might be explained, however, by the fact that there is a second card in the index:

|

|

|

Note that all the information is exactly the same (birth date, parents names, etc.), except in this card it only shows the surname as Traurig. They both reference the same ledger line (115). So what does the ledger, which is the original record, say?:

| Ferdinand Traurig birth ledger entry (click to enlarge) |

You may need to click on the image to enlarge it if you want to see it. Ferdinand is unquestionably listed as Ferdinand Traurig, as is his father Israel Wolf, who comes originally from Pilzno apparently. So where did the Trauring name come from at all? Well, the record continues onto the next page where you can see a note at the far right that mentions the Trauring name:

| Ferdinand Traurig birth ledger entry, part 2 (click to enlarge) |

Okay, so we have a Trauring which was originally Traurig, except they’re from Pilzno, not Kanczuga. Are they related to my family? Not sure. Possibly this is an independent change from Traurig to Trauring by another family. One additional piece of information that can be gleaned from the birth record is that it actually gives a file number and date for when the surname was changed (presumably in Pilzno). The date of the name change was April 1, 1873 (almost exactly 140 years ago).

I contacted the archive in Pilzno about the name change record and was told all Jewish records were destroyed in the war. Not sure how a name change record is a ‘Jewish’ record. Indeed it seems strange that name change records would be divided by religion at all. It’s very possible no name change records exist from 1873 in Pilzno, but I wouldn’t rely on the response from the archive there to determine that for sure. Whether this is worth pursuing beyond this point is not clear to me. If this is a member of my family, the date of the name change would be consistent with my own family, which was Traurig in 1862 but Trauring in 1882.

Ferdinand Traurig (II)

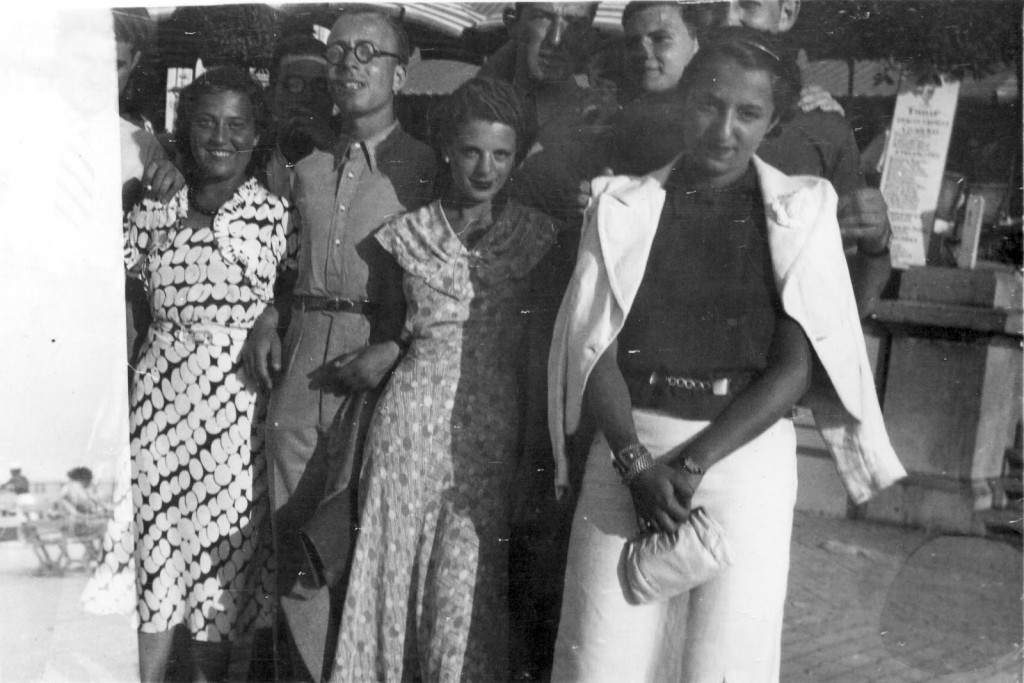

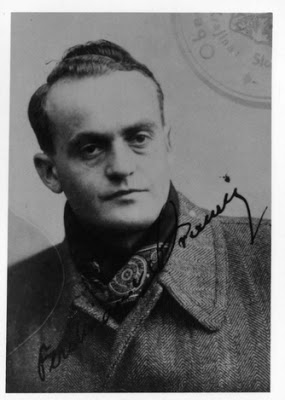

There’s another Ferdinand Traurig, except he doesn’t become a Trauring, but rather he becomes a Vesely. This is a much simpler story, thankfully spelled out by Ferdinand’s niece in a comment on Yad Vashem’s photo archive. If you’re not familiar with Yad Vashem’s photo archive, it’s a great resource. Yad Vashem teamed up with Google in 2011 to make their massive photo archive searchable online. Searching for Traurig there returns several results, including this photo of one Ferdinand Traurig:

|

| Ferdinand Traurig from Prešov, Czechoslovakia (Yad Vashem) |

One of the great features of Yad Vashem’s archive is that visitors can add comments to the photos. In this case, someone named Vanessa (in fact it seems there are two comments merged together from two people) added the following comment to the above photo:

Ferdinand was someone who I loved being around and learnt alot from. A great man who fought the Nazi’s during the Holocaust and fought for Judaism after the war in Australia by setting up a synagogue and raising his child and grandchildren in a Jewish home. May his memory live on through the Judaism that his family practice for many many more generations to come.A wonderful man whom I am proud to call my uncle. Ferdinand was one of 12 children of Yitzhak and Malvina Traurig. Both of his parents and 5 of their children survived World War 2. The list of bothers and sisters were Heinrich, Izidor, Zigmund, David (my father) Ferdinand, Shanyi, Manu, Esther, Annus, Ruzena, Hugo and Josef .Together with their parents, Izidor, Zigmund, David, Ferdinand and Josef survived the war. Many of the other children were married with families who all perished during the Shoah. The family has and is a proud family of Kohanim. The parents and the surviving children [except for Zigmund who remained in Czechoslovakia and was a distinguished scientist ] moved to Australia after the war. The family remains an orthodox Jewish family with a proud heritage. After the war parts of the family changed their family name. Traurig in German means “melancholy or sad”–my father David together with Ferdinand and Josef changed the family name to” Vesely” meaning in Slovak “happy”. Zigmund changed his family name to “Smutny” which is the Slovak equivalent to “sad” The children, grandchildren and now hopefully the great grandchildren of the surviving brothers still keep in close contact and we try to fulfill the hopes and aspirations of those who have gone before us.This is a photo of my grandfather, Ferdinand Traurig. Passed away in 1997 in Sydney Australia. Ferdinand fought with the partisans during the war, his wife Ruzena (née Junger) was in a labour camp and then in hiding, with their only child placed in the care of a non Jewish family. Both Ferdinand, Ruzena and Judith (my mother) survived the war and came to Sydney to rebuild their lives with the remnants of their family.

May 29, 2011, 1:50 p.m.

From the comment we see that Ferdinand Traurig in this photo survived the war with his parents and several brothers, and most of them changed their surname to Vesely, which is Slovak for Happy. One brother changed his name to Smutny which is Slovak for Sad (keeping with the original meaning of the name in German). Here we have a real example of brothers with surnames that mean both Happy and Sad, and it wasn’t something forced upon them.

Doing a quick search online brings a bit more of the story, showing how the Traurig family arrived in Coogee, Australia (a suburb of Sydney) and started a new synagogue there that exists today.

No Sorrow

The Traurigs who made it to Australia were not the only ones to flip the meaning of their name in a new country after the Holocaust.

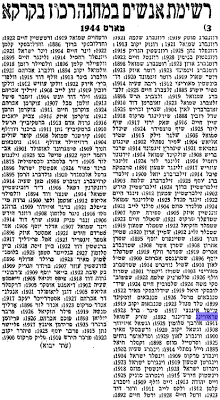

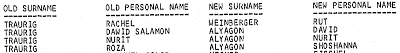

I originally came across information on this family in 2004 in the run up to IAJGS Int’l Jewish Genealogy Conference in Jerusalem. I had been in Israel less than a year at that point, and was not actively involved with genealogy in Israel yet, but I had volunteered to lay out the souvenir conference journal, and had met many of the people who were running the conference. For the conference, the local genealogy society had prepared a database of name changes that had been published in an official government paper between the years 1921-1948 (corresponding to the time of the British Mandate). This database was original created by Avotaynu, the Jewish genealogy publisher, and put onto microfiche. The database distributed at the conference was created by transcribing the images of the microfiche pages. This database was later put online (although it seems not to fully work now – oddly it seems the original surnames are missing from the search making it impossible to use for its intended purpose), but at the conference it was released on a CD to conference participants. Here is an image from the original microfiche:

|

| Traurig name changes in British Mandate Palestine (click to enlarge) |

I’m not clear on the first name change to Weinberger. That happened in 1946. It could of been because she married, or perhaps because she was taking the name of a different parent now that we was in another country. It’s probably not, however, an ideological name change.

The next three names, however, are a family that changed their name together in 1947 from Traurig to Al Yagon. Al Yagon in Hebrew means No Sorrow. Very similar to the change to Vesely by the Traurig family in Australia.

Another interesting change in the change of given name from Roza to Shoshana. A Shoshana in Hebrew is, you guessed it, a Rose.

After finding out about this Al Yagon family I tried to find them and indeed located descendants of those mentioned in these name change records. What happened next is an important lesson for genealogy researchers. As I was writing this article I decided to look back at my correspondance with the Al Yagon family. After a few e-mails back and forth confirming they were the ones whose family name was originally Traurig, I realized why the correspondance had ended. I was told there was an expert in the family history and I should contact him for more information. I was given his name – Meir Eldar – and his e-mail address. I had e-mailed him but not received a response. As I probably thought this family was not related to mine, I probably didn’t notice the lack of response and didn’t follow up. Maybe I had been given the wrong e-mail address, maybe my e-mail was swallowed by a spam filter, I really don’t know. What I do know is that I forgot about the e-mail in 2004 and I never reached this family history expert on the Traurig family. Now in 2013 while researching this article, I corresponded with another Traurig researcher, who informed me that her cousin, the same Meir Eldar, had only recently stopped responding to e-mails due to his deteriorated health. Had I reached him eight years ago, what might I have found out? It’s impossible to know now. This is why it’s important to keep tabs on all the e-mails and other correspondance one has out there at any given time.

Conclusion

So what do we have?

We have my Traurig family from Kańczuga that changed their name to Trauring around the 1870s.

We have the Israel Wolf/Ferdinand Traurig family that came from Pilzno, that changed their name also to Trauring around the same time.

We have the Traurig family from Prešov that changed their name to Vesely and Smutny in Australia, after surviving the Holocaust.

We have the Traurig family that arrived in Pre-State Israel in 1946, and changed their name to the Hebrew Al Yagon.

So four different Traurig families, who ended up with four different surnames. These, of course, being the ones I know about.

What name-change stories have you run into when researching your family history? Does anyone have other example of a name that was changed in so many ways?