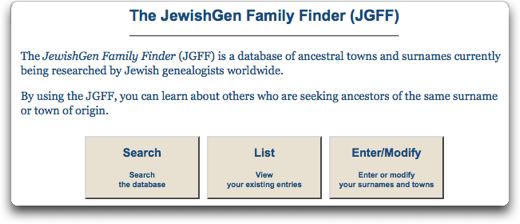

I’ve written before about the importance of using the JewishGen Family Finder (JGFF). I’ve even written about it on the JewishGen blog, see: JewishGen Basics: The JewishGen Family Finder (JGFF). The basic concept is that users add surname/town pairs to the database, and other users search for their surnames and towns, and can contact the other people researching the same names and towns. It can’t be understated how important the JGFF is for Jewish genealogy research, as a central point of connection for families that have become split up over the past century and more.

So it should come as no surprise that I made an effort to add links to JGFF on the towns in the B&F Compendium of Jewish Genealogy. When I launched it last year, the roughly one thousand Polish towns had links to their search results in the JGFF. I spent a lot of time verifying the links and making sure I only added links to towns that had listings. That, however, was a mistake.

The reason it was a mistake to only link to JGFF when there were listings, was that it could never be up to date, and if your family was from a town that had no results, you wouldn’t be aware of that fact. So now I link to all towns in the compendium. If you’re researching a town your family came from, and you click on the JGFF link and get no results, make sure to add your family!

Of the roughly thousand initial towns added to the compendium last year, only 59 had no listings in the JGFF. I know this because I had to add those 59 links to the compendium recently. Those towns were:

Aurelów

Baczki

Banie

Białaczów

Brańszczyk

Buk

Chojnów

Cyców

Dańdówka

Dębowa Góra

Gidle

Golczewo

Gołonóg

Górowo Iławeckie

Grabów nad Prosną

Jastrząb

Kamień

Kamionka

Kosewo

Kowale Pańskie

Krasiczyn

Kraśniczyn

Krościenko

Lądek-Zdrój

Lasocin

Łazy

Leszno

Lewin Brzeski

Lipsko

Liw

Łopianka

Lwówek Śląski

Łyszkowice

Miedzno

Mikstat

Mniszew

Mokobody

Nowa Brzeźnica

Nowe Brzesko

Olsztyn

Ośno Lubuskie

Pasłęk

Pełczyce

Piotrkowice

Poręba Średnia

Przybyszew

Rachów

Siedleczka

Skierbieszów

Skryhiczyn

Sobienie Jeziory

Środa Śląska

Stromiec

Tarnawa Niżna

Wąbrzeźno

Wińsko

Wola Krzysztoporska

Zbuczyn

If you see towns where your family came from, then I strongly recommend adding your family to the JGFF listings for those towns. Keep in mind that you need to be logged in to JewishGen for the JGFF links to work. If you try to use them without being logged in, then you will be prompted to log in. If you need help figuring out how to enter your family and town information into JGFF, see my article on the JewishGen blog.

I don’t know exactly how many of the more than two hundreds Polish towns I added yesterday had listings in JGFF since I linked to all of them, but I would say that based on spot checks as I added them that roughly half of them had entries. Even so, keep in mind that even in the original towns there may only be a few entries. The 59 towns above were only the ones that had no entries, but there are many more that only have a handful of entries. Go add your surnames and ancestral towns to JGFF today (and as I explain in my original article – don’t do it anonymously).