For those with family from Vienna, the web site Genteam.at is an indispensable genealogy resource. It’s a volunteer-run site that has indexed over 8 million records from Vienna, including many Jewish records including birth, marriage and death records, obituaries, cemetery records, directories of professionals, membership lists of lodges (including B’nai Brith), conversion records, and more. Access to their database is free, you just need to register for a free account on their site before you can search.

Recently, the site added 482,000 new records, including a 180,000 records from the Jewish community of Vienna – marriage and death records from 1913-1928, and birth records up to 1913. I believe this record addition is what brought them over 8 million records, so congratulations to the whole team of volunteers at Genteam.at, past and present, who have accomplished an amazing task.

The records indexed all conform to the Austrian privacy laws, which is why the records end when they do. Presumably next year they will add birth records through 1914, etc. In two years my grandfather’s birth record from 1915 will presumably be published on the site. For more on my grandfather, see Friends from Antwerp – and is that a famous Yiddish poet? and Remembering my grandfather.

Keep in mind that while sites like this (located in Austria) cannot publish indexes to these records due to privacy laws, some later records were microfilmed prior to the current privacy laws, and already exist in the Family History Library. It’s unclear to me whether those records can (or will) be indexed online by FamilySearch.org, or whether they too will not provide them online, even if someone can view the records on microfilm in any Family History Center.

Right now, FamilySearch.org has a record set called Austria, Vienna, Jewish Registers of Births, Marriages, and Deaths, 1784-1911, which has the images online (over 200,000), but is not indexed. That means you can look at the images and try to find the record you want, but there is no way to search it.

If you search their catalog, however, there exists many more Jewish records from Vienna, including:

- Register of Jewish births, marriages, deaths, and indexes for Wien (Vienna), Niederösterreich, Austria. Includes Leopoldstadt, Ottakring, Hernals, Währing, Fünfhaus and Sechshaus. 1826-1943

- Circumcisions and Births 1870-1914

- Jewish converts in Vienna 1782-1868

- Index to the register books of the Jewish community, 1810-1938

- Births, marriages and deaths of Austrian Jewish military personnel in Wien, Niederösterreich, Austria. 1914-1918.

- Reports the exit from the Jewish faith: 18000 defections from Judaism in Vienna, 1868-1914

- Names of Jewish infants who were forcibly baptized Christians and left with foundling hospitals in Vienna, Austria. The mothers of the infants were primarily servants and manual laborers from Hungary, Slovakia, Bohemia and Moravia. Each entry includes genealogical data. 1868-1914.

- Genealogies and biographies of the Jewish upper class of Vienna, Austria, 1800-1938.

Eventually, these records will also presumably make it to FamilySearch.org, and eventually they will be indexed as well. Many of these records are clearly the same records making their way onto Genteam.at – it’s even possibly that Genteam.at is working form the FHL microfilms to create their indexes.

The odd thing is that the online record set covers the dates 1784-1911, while the microfilm record set covers 1826-1943. The question is if the microfilm set only goes back to 1826, then how does the online set go back to 1784? Even stranger, if you click through to the wiki page describing the record set, it says the records cover only the years 1850-1896. Perhaps the online records go back further because they include other record sets like the conversion data, which covers the years 1782-1868 – but if that’s the case then why doesn’t the online set go back those extra two years to 1782? It’s very confusing.

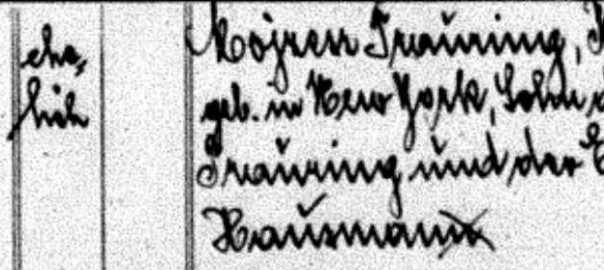

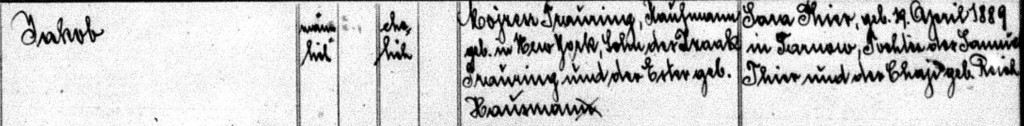

In any case, just to be clear, there are many Vienna records available, even if they apparently run counter to the Austrian privacy laws (which seem to ban the release of birth records for 100 years). As proof that these records are accessible via microfilm, I’ll just end with this birth record for my grandfather who recently passed away at the age of 98, which I acquired from the FHL microfilms with the help of a local researcher a few years ago: